By Tanner Henson

Before diving into the legal challenges that surrounded North Carolina’s 2022 congressional redistricting, it is important to understand the recent history of redistricting in the state. In 2010, a wave election year for North Carolina Republicans, the GOP stunned those who follow state politics by securing majorities in both houses of the General Assembly for the first time since 1898.[1] Underscoring the enormity of this shift, the State Senate flipped from a Democratic majority of 30–20 to a Republican majority of 31–19, while the State House of Representatives flipped from a Democratic majority of 68–52 to a Republican majority of 68–52.[2]

Having endured severe Democratic gerrymanders at the congressional level,[3] following their wins in 2010, legislative Republicans redrew congressional maps to generate a 10–3 Republican advantage.[4] Under the North Carolina Constitution, congressional districts are drawn by the General Assembly and are not subject to the governor’s veto.[5] Partially because of this structure, the Democratic aligned National Redistricting Action Fund, which is closely associated with former Attorney General Eric Holder, has frequently brought suit to enjoin maps favoring the GOP.[6] Under North Carolina statutes, when a congressional map is challenged in state court, a three-judge panel, composed of Wake County’s senior superior court judge and two additional superior court judges appointed by the chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court, have exclusive jurisdiction.[7] Appeals from this panel go directly to the state supreme court.[8]

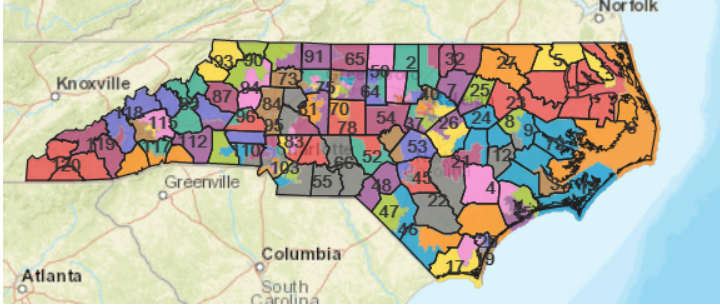

In 2018, North Carolina Republicans saw their congressional advantage eroded from 10–3 to 8–5, following a federal court ruling that Republican state legislators “had violated the First amendment and the equal-protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment when they drew congressional lines that favored their party.”[9] Given these losses, legislative Republicans went into 2022 looking to regain the lost seats.[10] Following the 2020 Census, buoyed by North Carolina’s increasing population, which resulted in the state gaining a fourteenth congressional seat,[11] legislative Republicans again drew congressional maps that would have generated a 10–4 majority, even in bad political climates for the GOP.[12] Likely due to an ideological shift in the North Carolina Supreme Court, which now has a 4–3 Democratic majority,[13] this year, Democratic–backed groups sued the General Assembly in state court, seeking to have the maps enjoined, according to the process outlined above.[14]

In a 260-page order, a three-judge panel upheld the map, ruling that “[a]t no point has restriction of redistricting for partisan advantage ever been made part of any North Carolina Constitution.”[15] The panel viewed the constraints on redistricting enumerated in the North Carolina Constitution—that members of Congress should represent nearly equal numbers of constituents, that districts should be contiguous, that maps should split as few counties as feasible, etc.—as exhaustive.[16] The panel was unwilling to infer that the equal protection and free speech clauses of the state constitution somehow limited the legislature’s redistricting power; rather, the court wrote that “[i]f the framers did intend to limit the partisan advantage that could be obtained through redistricting, ‘it is reasonable to presume it would have been declared in direct terms and not be left as a matter of inference.’”[17] The panel stressed that the judiciary should not involve itself in such a purely political question, writing, “[w]ere we as a Court to insert ourselves in the manner requested, we would be usurping the political power and prerogatives of an equal branch of government. Once we embark on that slippery slope, there would be no corner of legislative or executive power that we could not reach.”[18]

However, in an order dated February 14, the North Carolina Supreme Court reversed the lower court, writing that the congressional map was “unconstitutional beyond a reasonable doubt under the free elections clause, the equal protection clause, the free speech clause, and the freedom of assembly clause of the North Carolina Constitution.”[19] The court reasoned that to comply with the constraints in the North Carolina Constitution, “the General Assembly must not diminish or dilute any individual’s vote on the basis of partisan affiliation.”[20] The court further explained that when the legislature enacts a map that makes it more difficult for an individual to join with likeminded voters to elect a governing majority, “the General Assembly unconstitutionally infringes upon that voter’s fundamental right to vote.”[21]

Following its order, the court allowed the General Assembly a second opportunity to draw less partisan maps and suspended candidate filing during that period.[22] However, the legislature enacted another congressional map that would have likely resulted in a 10–4 Republican advantage.[23] On February 23, the reviewing three-judge panel rejected the second map drawn by the legislature and adopted a map drawn by four non-partisan special masters, which will likely result in either an 8–6 Republican advantage, or an evenly divided delegation.[24] The state supreme court subsequently approved of this map and reopened candidate filing.[25]

On February 25, the Speaker of the North Carolina House of Representatives, Tim Moore, filed an emergency appeal in the United States Supreme Court seeking to overturn the court-enacted congressional map,[26] arguing that the court-imposed map “usurped the legislature’s power to regulate congressional elections under the U.S. Constitution.”[27] The appeal—Moore v. Harper—was placed on the Court’s shadow docket.[28]

Moore asked the Court to expand its prohibition against judicial interference with redistricting to cover state courts.[29] The theory underlying the Speaker’s appeal is known as the independent state legislature doctrine.[30] The theory is grounded in Article I, Section 4 of the United States Constitution, which gives state legislatures the authority to determine the time, place, and manner of congressional elections.[31] While this grant of authority has been viewed as giving legislative leaders the authority to set the ground rules for elections, it has not previously prevented state court process.[32] However, Speaker Moore and legislative Republicans argued that the legislature’s power under the Constitution is supreme, thereby preventing state court interference, even in instances where a map might violate the state constitution.[33] Particularly, Moore argued that the state supreme court interfered with legislative authority to regulate the manner of elections when it enacted a map drawn by its own special masters.[34]

For over one-hundred years, the Supreme Court has rejected this expansive view of the powers granted to state legislatures.[35] In accord with this precedent, the Court rejected Moore’s appeal.[36] However, fissures are starting to appear in what had seemed to be a settled area of law. First, at least four of the Court’s current justices signaled some willingness to examine the independent state legislature doctrine during former President Trump’s challenges to the 2020 election.[37] Second, while the Court’s decision in Moore left in place the court-imposed maps, it did so over a pointed dissent penned by Justice Alito, who was joined by Justices Thomas and Gorsuch.[38] The dissenters noted that the “case present[ed] an exceptionally important and recurring question of constitutional law, namely, the extent of a state court’s authority to reject rules adopted by a state legislature for use in conducting federal elections.”[39] Justice Alito stressed the importance of answering this question, before lamenting that the Court had missed another opportunity to do so.[40]

Justice Kavanaugh wrote separately, concurring in the denial of Moore’s application for a stay.[41] While Kavanaugh ultimately voted with the majority, he did so only because he felt that it was “too late for the federal courts to order that the district lines be changed for the 2022 primary and general elections[.]”[42] Kavanaugh largely agreed with Justice Alito that Moore had “advanced serious arguments on the merits” and posed a question that will “keep arising until the Court definitively resolves it.”[43]

This is likely not the end of the road for the independent state legislature doctrine. We now know at least four justices are willing to entertain the doctrine, enough to grant certiorari. Some “Court watchers” are predicting that the fate of the theory rests on the vote of Justice Amy Coney Barrett, the only justice who has been, as of yet, completely silent on the merits of the doctrine.[44] Time will tell.

[1] Tracy W. Kimbrell & R. Bruce Thompson II, 2010 North Carolina Election Analysis, Parker Poe (Nov. 3, 2010), https://www.parkerpoe.com/news/2010/11/2010-north-carolina-election-analysis.

[2] Id.

[3] See Noah Tom Bullock, North Carolina’s Congressional Primaries Are a Mess Because of These Maps, NPR (Mar. 10, 2016, 5:00 AM), https://www.npr.org/2016/03/10/469548881/north-carolinas-congressional-primaries-are-a-mess-because-of-these-maps. One district, the twelfth, looked reminiscent of a snake, running along I-95 for approximately 80 miles. The district spanned from Charlotte to Winston-Salem, and at times was no wider than the interstate it tracked.

[4] Scott Bland, Court Throws Out N.C. Congressional Map Before Election, Politico (Aug. 27, 2018, 7:54 PM), https://www.politico.com/story/2018/08/27/north-carolina-congressional-map-thrown-out-798609.

[5] N.C. Const. art. II, § 22(5).

[6] Patrick Rodenbush, Eric Holder and Marc Elias Discuss NRAF Redistricting Lawsuits, Nat’l Redistricting Action Fund (Apr. 27, 2021), https://redistrictingaction.org/news/eric-holder-and-marc-elias-discuss-nraf-redistricting-lawsuits.

[7] Doug Spencer, All About Redistricting North Carolina, Loyola L. Sch., https://redistricting.lls.edu/state/north-carolina/?cycle=2020&level=Congress&startdate=2021-11-04 (last visited Mar. 23, 2022).

[8] Id.

[9] Bland, supra note 4.

[10] See Michael Wines, North Carolina Court Says G.O.P. Political Maps Violate State Constitution, N.Y. Times (Feb. 4, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/04/us/north-carolina-redistricting-gerrymander-unconstitutional.html.

[11] Bill O’Neil, North Carolina Gains Seat in Congress After Census Results Released, WXII12 (Apr. 26, 2021, 8:43 PM), https://www.wxii12.com/article/north-carolina-census-results-additional-congress-seat/36255789.

[12] Wines, supra note 10.

[13] Id.

[14] See supra notes 7–8 and accompanying text.

[15] Unanimous Three-Judge Panel Upholds N.C. Election Maps, Appeal Likely, Carolina Journal (Jan. 11, 2022, 5:43 PM), https://www.carolinajournal.com/news-article/unanimous-three-judge-panel-upholds-n-c-election-maps-appeal-likely/.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] Ethan Cohen, North Carolina Supreme Court Strikes Down Redistricting Maps, CNN Politics (Feb. 4, 2022, 7:59 PM), https://www.cnn.com/2022/02/04/politics/north-carolina-redistricting-struck-down/index.html.

[20] Harper v. Hall, 868 S.E.2d 499, 546 (N.C. 2022).

[21] Id. at 544.

[22] Id. at 559.

[23] Michael Wines, North Carolina Court Imposes New District Map, Eliminating G.O.P Edge, N.Y. Times (Feb. 23, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/23/us/politics/north-carolina-maps-democrats.html.

[24] Id.

[25] Id.

[26] What Redistricting Looks Like in Every State, FiveThirtyEight (Mar. 22, 2022, 4:50 PM), https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/redistricting-2022-maps/north-carolina/.

[27] Id.

[28] Moore v. Harper, SCOTUSblog, https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/moore-v-harper/ (last visited Mar. 7, 2022).

[29] Adam Liptak, Supreme Court Allows Court-Imposed Voting Maps in North Carolina and Pennsylvania, N.Y. Times (Mar. 7, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/07/us/supreme-court-voting-maps.html (arguing “that the state legislature has sole responsibility for drawing congressional districts and that state courts have no role to play”).

[30] Richard L. Hasan, North Carolina Republicans Ask SCOTUS to Decimate Voting Rights in Every State, Slate (Feb. 25, 2022, 7:32 PM), https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2022/02/north-carolina-republicans-scotus-gerrymandeering-assault.html.

[31] U.S. Const. art. I, § 4.

[32] Hasan, supra note 30.

[33] Id.

[34] Rusty Jacobs, Supreme Court Filing in NC Redistricting Matter Poses Thorny Questions for Conservatives, WFAE 90.7 (Feb. 28, 2022, 5:03 PM), https://www.wfae.org/politics/2022-02-28/supreme-court-filing-in-n-c-redistricting-matter-poses-thorny-questions-for-conservatives.

[35] Hasan, supra note 30.

[36] Liptak, supra note 29.

[37] Id.

[38] Moore v. Harper, No. 21A455, slip op. at 1 (U.S. Mar. 7, 2022) (Alito, J., dissenting), https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/21a455_5if6.pdf.

[39] Id. s

[40] Id.

[41] Moore v. Harper, No. 21A455, slip op. at 1 (U.S. Mar. 7, 2022) (Kavanaugh, J., concurring), https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/21a455_5if6.pdf.

[42] Id. at 2.

[43] Id. at 1.

[44] Ian Millhiser, The Fate of American Elections Is in Amy Coney Barrett’s Hands, Vox (Mar. 4, 2022, 8:00 AM), https://www.vox.com/22958543/supreme-court-gerrymandering-redistricting-north-carolina-pennsylvania-moore-toth-amy-coney-barrett.