By Samuel Gilleran

In a sweeping, 357-page ruling released yesterday afternoon, a three-judge panel of North Carolina Superior Court judges unanimously held that partisan gerrymandering violates multiple provisions of the North Carolina Constitution,[1] including the Equal Protection Clause,[2] the Free Elections Clause,[3] and the Freedom of Speech and Freedom of Assembly Clauses.[4]

The panel then proceeded to enjoin the use of the maps in the 2020 primary and general elections, ordered the General Assembly to enact new maps within two weeks, and forbade the use of “[p]artisan considerations and election results data.”[5] The panel further decreed that the General Assembly could not use the current map “as a starting point for drawing new districts, and no effort may be made to preserve the cores of invalidated 2017 districts.”[6] The panel forbade the use of outside consultants without Court approval and demanded that “the entire remedial process” must occur “in full public view. At a minimum, this requires all map drawing to occur at public hearings, with any relevant computer screen visible to legislators and public observers.”[7] Finally, the panel “retain[ed] jurisdiction” to adjust the dates of the 2020 primary elections in the event that such an adjustment was “necessary to provide effective relief in this case.”[8]

The panel noted that the allegations of partisan gerrymandering were essentially uncontested.[9] After all, in the related redrawing of the congressional district lines, Rep. David Lewis (R-Harnett), a leader in the Republican redistricting effort, plainly stated his belief that a “political gerrymander [was] not against the law” in urging the adoption of a map that would “give a partisan advantage to 10 Republicans and 3 Democrats because I do not believe it’s possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and 2 Democrats.”[10] The real question at issue was whether such gerrymandering was both proscribed under the North Carolina Constitution and justiciable by the North Carolina courts. The panel answered both questions affirmatively.

Before the panel expounded its holdings under the state constitution, it first explained why the Supreme Court’s opinion in Rucho v. Common Cause[11] did not control. As the panel noted, the Supreme Court explicitly reserved the issue of partisan gerrymandering for state review. It quoted the high court’s assertion that its opinion in Rucho did “not condone excessive partisan gerrymandering” and did not “condemn complaints about districting to echo into a void.”[12] “Rather, the Supreme Court held, ‘[t]he States . . . are actively addressing the issue on a number of fronts,’ and ‘[p]rovisions in state statutes and state constitutions can provide standards and guidance for state courts to apply.’”[13] The panel held that such provisions were present in North Carolina’s constitution.

First, the panel examined the Free Elections Clause. It noted that this clause “is one of the clauses that makes the North Carolina Constitution more detailed and specific than the federal Constitution in the protection of the rights of its citizens.”[14] The panel traced the evolution of the Free Elections Clause throughout the history of North Carolina’s legal system and concluded that it provides a justiciable right to North Carolinians; it is not merely hortatory or aspirational language.[15] It specifically pointed to a 1971 revision of the state constitution in which the wording of the clause was changed from “all elections ought to be free” to “all elections shall be free.”[16] “This change was intended to ‘make [it] clear’ that the Free Elections Clause and the other rights secured to the people by the Declaration of Rights ‘are commands and not mere admonitions’ to proper conduct on the part of the government.”[17]

The panel went on to hold that “[t]he partisan gerrymandering of the 2017 Plans strikes at the heart of the Free Elections Clause. . . . Elections are not free when partisan actors have tainted future elections by specifically and systematically designing the contours of the election districts for partisan purposes and a desire to preserve power. In doing so, partisan actors ensure from the outset that it is nearly impossible for the will of the people—should that will be contrary to the will of the partisan actors drawing the maps—to be expressed through their votes for State legislators.”[18]

In holding that North Carolina’s Free Elections Clause proscribed partisan gerrymandering, the panel’s logic tracked that of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which in 2018 held that a similar clause in that state’s constitution forbade partisan gerrymandering.[19] In that case, the court overturned a Republican gerrymander of Pennsylvania’s congressional districts; in the ensuing election, Democrats flipped three seats and came within 11,239 votes in three more.[20] Were it not for Pennsylvania’s political geography, in which there are 260,000 excess Democratic votes in the 3rd Congressional District (Philadelphia), Democrats could have won even more seats.[21]

Second, the panel examined North Carolina’s Equal Protection Clause.[22] The panel noted that the state version of the clause has been interpreted more broadly than the federal courts have interpreted the federal clause.[23] And so the panel relied on previous state supreme court precedents to explicate that North Carolina’s Democratic voters were being treated unequally and that because the fundamental right to vote was implicated, strict scrutiny applied.[24]

Third, the panel turned to the Free Speech and Free Assembly claims. The panel held that “the 2017 Plans discriminate[d] against . . . Democratic voters based on their protected expression and association” and that “[d]iscriminating against citizens based on their political beliefs does not serve any legitimate government interest.”[25] The panel also held that the 2017 plans were unconstitutional under a retaliation theory of the Free Speech and Free Assembly Clauses; because Democratic voters had past protected political activity (i.e., voting for Democratic candidates) and because Republican mapmakers had chosen Democrats for negative treatment based on their protected activity, a retaliation claim was successful.[26]

Finally, the panel had to decide whether the claims were justiciable. After all, the Supreme Court had essentially held just a few months prior that while partisan gerrymandering was bad behavior, it was powerless to stop it due to a lack of judicially manageable standards. The panel held that the question of partisan gerrymandering did not fall within the political question doctrine; it is justiciable.[27] The panel specifically noted that one of the main purposes of the judicial branch of government was to be a check on the legislature’s desire to aggrandize power to itself. Citing a case from 1787, dating all the way back to the founding of the Republic, the panel declared:

“If unconstitutional partisan gerrymandering is not checked and balanced by judicial oversight, legislators elected under one partisan gerrymander will enact new gerrymanders after each decennial census, entrenching themselves in power anew decade after decade. When the North Carolina Supreme Court first recognized the power to declare state statutes unconstitutional, it presciently noted that absent judicial review, members of the General Assembly could ‘render themselves the Legislators of the State for life, without any further election of the people.’ Those legislators could even ‘from thence transmit the dignity and authority of legislation down to their heirs male forever.’ Extreme partisan gerrymandering reflects just such an effort by a legislative majority to permanently entrench themselves in power in perpetuity.”[28]

Notably, the panel rejected the argument that because gerrymandering had a long history, it was therefore constitutional. Citing to the seminal voting rights case Reynolds v. Sims, the panel stated that “widespread historical practices does not immunize governmental action from constitutional scrutiny.”[29] Merely because a practice was longstanding – and even, as in this case, engaged in by one of the Plaintiffs (i.e., the North Carolina Democratic Party) during the many years when it was in power – does not somehow eliminate the rights reserved by North Carolinians under the state constitution. The panel also rejected the idea that it needed to find a bright-line rule for how much partisan gerrymandering was too much, the question that so plagued the Supreme Court in Rucho. Instead, the panel stated the obvious: “[t]his case is not close.”[30] In essence, the panel held that, wherever the line is, this set of facts is so far past that line that Plaintiffs’ entitlement to relief is indisputable.

The reaction to the panel’s decision was swift. Sen. Jeff Jackson (D-Mecklenburg) tweeted that the ruling was “the single best news [he] ha[d] ever heard” during his time in the legislature,[31] while Rep. Graig Meyer (D-Orange) called the ruling “a big win for democracy and a game changer for 2020.”[32] But the biggest news came from Republican Senate Majority Leader Phil Berger (R-Rockingham), who announced that Republicans would not appeal the decision to the state Supreme Court. Although castigating the panel’s decision, Sen. Berger stated that “[n]early a decade of relentless litigation has strained the legitimacy of this state’s institutions, and the relationship between its leaders, to the breaking point. It’s time to move on. To end this matter once and for all, we will follow the court’s instruction and move forward with adoption of a nonpartisan map.”[33] Election law scholar Rick Hasen suggested a few reasons why Republicans elected not to appeal, including the simple facts of sure loss in the North Carolina Supreme Court and the greater precedential value of the inevitable negative decision from that court.[34]

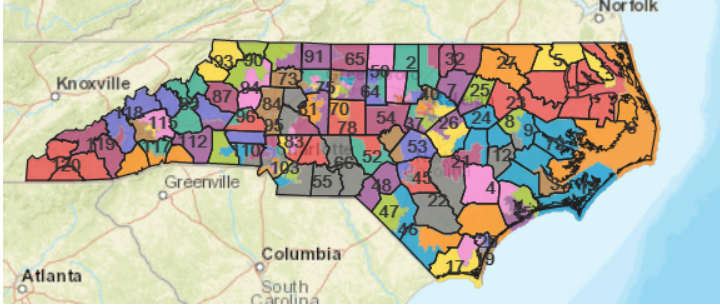

What are the practical ramifications of this decision? For the first time in a long time, Democrats truly believe they can win back majorities in each house of the legislature.[35] Republicans currently maintain a 65-55 margin in the state house, and given the sheer number of districts identified in the decision as unconstitutionally gerrymandered, Democrats have to feel good about the prospects of taking back at least that chamber. Democrats carried a majority of the two-party vote in 2018,[36] and it is historically likely that the electorate in 2020, a presidential year, will be younger and more racially diverse than in 2018, a midterm year.[37]

Judging from the simulations run by political scientists and adjusting for a 2020 political environment, Democrats have a strong chance at flipping House seats in Columbus County,[38] Cumberland County,[39] Franklin County,[40] Pitt County,[41] Guilford County,[42] Forsyth County (possibly two)[43], New Hanover County,[44] Onslow County,[45] Anson County,[46] and Alamance County.[47] If Democrats were able to flip even six of these eleven targets, it would give them a 61-59 majority in the state house, all other things being equal.

Similarly, on the Senate side, Republicans retain a 29-21 majority,

so the Democrats would have to flip five seats. The panel’s ruling gives Democrats

a reasonable chance at flipping seats in Mecklenburg County[48]

and Wake County,[49]

but in other gerrymandered districts that would be unwound by the ruling, such

as in Guilford County and New Hanover County, Democrats managed to defeat the

gerrymander in 2018. That said, unwinding the gerrymander makes the playing

field different and, in a good year, could allow Democrats to take Senate seats

that they ordinarily would not. In addition, when decennial redistricting occurs

in 2021 after the 2020 census, it could be that a few seats will shift from

rural to suburban and urban areas, thereby helping Democratic chances moving

forward.

[1] Common Cause v. Lewis, No. 18-cv-14001, slip op. at 352–53 (N.C. Super. Ct. [Wake] Sep. 3, 2019), https://big.assets.huffingtonpost.com/athena/files/2019/09/03/5d6ec7bee4b0cdfe0576ee09.pdf.

[2] N.C. Const. art. I, § 19.

[3] N.C. Const. art. I, § 10.

[4] N.C. Const. art. I, §§ 12, 14.

[5] Common Cause, slip op. at 353–55.

[6] Id. at 355.

[7] Id. at 356.

[8] Id. at 357.

[9] Id. at 23.

[10] Hearing Before the J. Comm. on Redistricting, Extra Sess. 48, 50 (N.C. Feb. 16, 2016) (statement of Rep. David Lewis, Co-Chair, J. Comm. on Redistricting), redistricting.lls.edu/files/NC%20Harris%2020160216%20Transcript.pdf.

[11] 139 S. Ct. 2484 (2019) (holding partisan gerrymandering non-justiciable under the federal Constitution).

[12] Common Cause, slip op. at 299 (quoting Rucho, 139 S. Ct. at 2507).

[13] Id. (emphasis added in Common Cause).

[14] Id.

[15] Id. at 303–04.

[16] Id. at 304 (emphasis added in Common Cause) (quoting N.C. Const. art I, § 10) (comparing 1868 version to 1971 version).

[17] Id. (quoting N.C. State Bar v. DuMont, 304 N.C. 627, 635, 639, 286 S.E.2d 89, 94, 97 (1982)).

[18] Id. at 305.

[19] See League of Women Voters of Pa. v. Commonwealth, 178 A.3d 737, 804 (Pa. 2018).

[20] Pennsylvania Election Results, N.Y. Times (last updated Dec. 19, 2018, 5:12 PM), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/11/06/us/elections/results-pennsylvania-elections.html.

[21] Id.

[22] Common Cause, slip op. at 307.

[23] Id. at 308–09.

[24] Id. at 315–16.

[25] Id. at 328.

[26] Id. at 329–31.

[27] Id. at 334.

[28] Id. at 333 (quoting Bayard v. Singleton, 1 N.C. 5, 7 (1787)).

[29] Id. (citing Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 582 (1964) (invalidating Alabama’s malapportioned legislative districts despite a history of malapportionment that dated back to the founding). North Carolina itself engaged in such malapportionment, which has been documented as early as 1792. See Thomas Rogers Hunter, The First Gerrymander?: Patrick Henry, James Madison, James Monroe, and Virginia’s 1788 Congressional Districting, 9 Early Am. Stud. 781, 819 (2011) (discussing a 1792 map that “severely overpopulated” congressional districts in the northeast corner of the state).

[30] Common Cause, slip op. at 341.

[31] Jeff Jackson (@JeffJacksonNC), Twitter (Sep. 3, 2019, 4:40 PM), https://twitter.com/JeffJacksonNC/status/1168987115637682176.

[32] Graig Meyer (@GraigMeyer), Twitter (Sep. 3, 2019, 4:44 PM), https://twitter.com/GraigMeyer/status/1168988126200705026.

[33] Nick Ochsner (@NickOchsnerWBTV), Twitter (Sep. 3, 2019, 5:27 PM), https://twitter.com/NickOchsnerWBTV/status/1168998919885508608.

[34] See Rick Hasen, North Carolina Republicans Won’t Appeal Gerrymandering Ruling, Promise “Nonpartisan” Map. What’s the End Game?, Election L. Blog (Sep. 3, 2019, 3:13 PM), https://electionlawblog.org/?p=107179.

[35] See Jeff Jackson (@JeffJacksonNC), Twitter (Sep. 3, 2019, 7:03 PM), https://twitter.com/JeffJacksonNC/status/1169023123938824194 (“With fair maps, we have a genuine shot at electing a state legislature that actually reflects the political will of our state.”).

[36] Common Cause, slip op. at 233.

[37] See, e.g., Matthew Yglesias, The 2018 Electorate Was Older, Whiter, and Better Educated Than in 2016, Vox (Nov. 12, 2018, 10:00 AM), https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/11/12/18083014/2018-election-results-turnout

[38] Common Cause, slip op. at 153.

[39] Id. at 157–58.

[40] Id. at 161–64.

[41] Id. at 164–69.

[42] Id. at 170–75.

[43] Id. at 181–85.

[44] Id. at 194–99.

[45] Id. at 199–203.

[46] Id. at 203–08.

[47] Id. at 209–15.

[48] Id. at 109–17.

[49] Id. at 117–23.