By Jenna White

As we all know, online advertising is almost impossible to escape. In fact, the average consumer in the United States sees about five thousand advertisements each day.[1] Even more frustrating to consumers is website publishers’ ever-increasing use of paywalls and subscriptions.[2] But publishers are not to blame. Google is. By monopolizing the digital ad tech market, Google has effectively diminished the monetary value of online advertising, forcing publishers to resort to paywalls and subscriptions to remain afloat.[3]

On January 24, 2023, the Department of Justice (DOJ) filed a Complaint against Google, alleging violations of the Sherman Act,[4] which imposes criminal penalties for monopolistic business practices.[5] Specifically, DOJ alleges that, through anticompetitive acquisitions and exploitation of its dominance in the tech industry, Google now controls the leading technology used by nearly every publisher and advertiser to buy and sell advertising space.[6] The Complaint compares Google’s practices to Goldman or Citibank owning the New York Stock Exchange.[7]

Digital Ad Technology

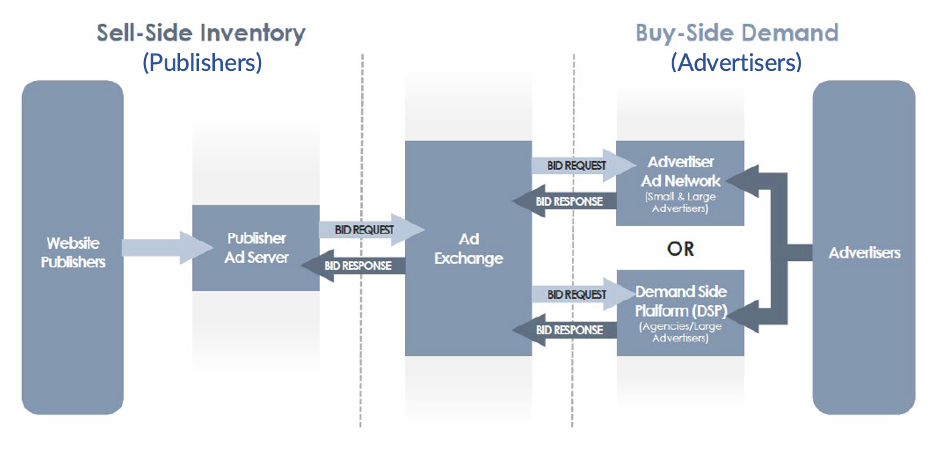

A brief breakdown of how advertisers purchase advertising space from publishers is necessary to understand the breadth of Google’s practices over the past two decades. Publishers sell space on their websites (referred to as inventory) that advertisers can buy to display their ads.[8] Inventory is offered by publishers either through direct sales (one-to-one negotiations with advertisers) or indirect sales, where inventory is offered through an intermediary, most commonly an ad exchange.[9] Ad exchanges are essentially auctions, where publishers offer ad space to advertisers and sell to the highest bidder.[10]

To facilitate these transactions, both advertisers and publishers use ad servers.[11] When a consumer accesses a website, the publisher’s ad server auctions the ad space through an ad exchange.[12] Advertisers use ad servers to connect them to these ad exchanges, make bids, and manage their ad campaigns.[13] Ad exchanges match advertisers and publishers by providing information about the website and the available ad space, and, depending on the scope of the ad exchange and the data available to it, provide information about the individual consumer viewing the website.[14] The figure below provides a simplified visual of the process, which collectively is referred to as the ad tech stack:[15]

Fig. 1

Google’s Takeover of the Ad Tech Stack

DOJ’s primary allegations rest on Google’s control of the entire ad tech stack. On the publisher side, Google owns the leading publisher ad server, Google Ad Manager, after its 2008 acquisition of DoubleClick for Publishers (DFP) for three billion dollars.[16] Google has grown DFP’s market share from sixty percent at the time of acquisition to ninety percent.[17] On the advertiser side, Google owns the leading advertiser ad servers, Google Ads and Display & Video 360 (DV360), as well as DoubleClick Campaign Manager, which manages advertiser’s ad campaigns.[18] Most importantly, Google’s 2008 acquisition of DoubleClick included the now-leading ad exchange AdX.[19] Google’s comprehensive ownership of the ad tech stack, on its own, would be unlikely to trigger violations of the Sherman Act. Nevertheless, Google has exploited its control over digital ad technology and siphoned an inconceivable fortune from the industry by stifling competition and innovation, depriving publishers of real choice and forcing advertisers to pay far more than they would in a competitive market.

Alleged Sherman Act Violations

In its Complaint, DOJ alleges violations under Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act.[20] Section 1 prohibits contracts, combinations, and conspiracies “in restraint of trade.”[21] DOJ alleges that Google has engaged in unlawful tying of AdX and DFP in violation of Section 1 by effectively requiring publishers to use both technologies.[22] The Supreme Court has defined tying as “an agreement by a party [here, Google] to sell one product [here, DFP] on the condition that the buyer [here, publisher] also purchases a different (or tied) product [here, AdX], or at least agrees that he will not purchase from any other seller.”[23]

DOJ argues that Google has unlawfully tied AdX and DFP primarily by offering ad space on Google Ads exclusively through AdX and limiting real-time access to AdX to publishers that use DFP.[24] Because advertisers cannot afford to forego Google Ads as a revenue stream, virtually all advertisers bid for inventory on AdX.[25] Therefore, publishers are effectively forced to auction inventory on AdX to reach Google’s advertising demand.[26] Additionally, AdX is configured to provide lower prices to publishers who access AdX auctions through non-Google (non-DFP) ad servers.[27] Together, these practices amount to unlawful tying of AdX and DFP, and DOJ will likely argue away any potential defenses or justifications.[28]

Section 2 of the Sherman Act prohibits monopolizing, attempting to monopolize, or conspiring to monopolize.[29] DOJ alleges that Google has violated Section 2 by monopolizing the publisher ad server market (through DFP), monopolizing or attempting to monopolize the ad exchange market (through AdX), monopolizing the advertiser ad network.[30] DOJ asserts that Google increased and maintained its monopoly in each of the relevant markets by acquiring DFP and AdX, restricting access to AdX to DFP, manipulating auction bids to benefit AdX, acquiring competitors, and restricting publishers’ ability to transact with competitors or at preferred prices.[31] DOJ emphasizes that “[a]lthough each of these acts is anticompetitive in its own right, these interrelated and interdependent actions have had a cumulative and synergistic effect that has harmed competition and the competitive process.”[32]

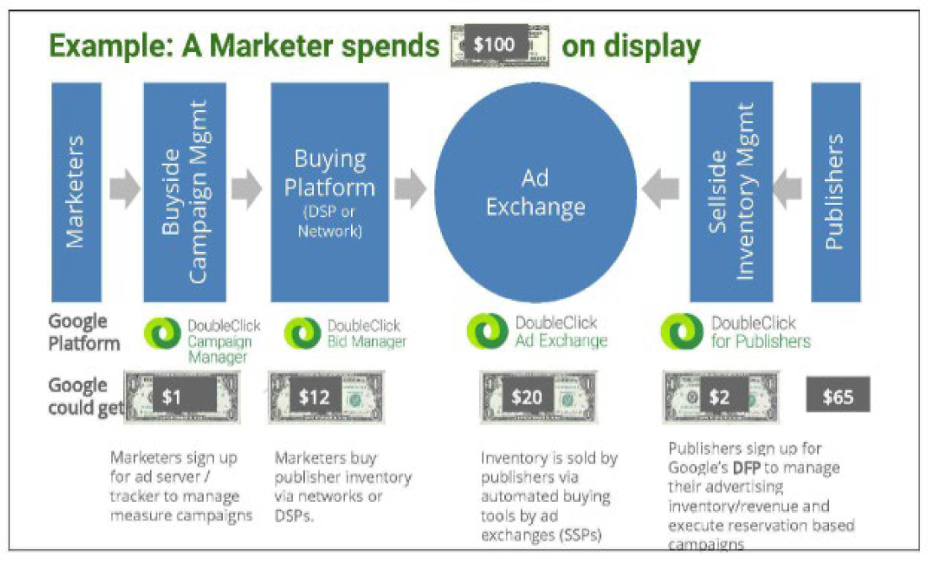

Through these anticompetitive practices, Google has made a fortune. When advertisers purchase ad space from publishers through AdX, Google skims off some of the purchase price for itself.[33] Additionally, Google charges advertisers and publishers for use of its ad servers.[34] Per internal Google documents, Google estimates that it retains about thirty-five cents of every dollar spent on digital ads, primarily through AdX, where it charges twenty percent for ad space bought.[35] The figure below demonstrates how control of the ad tech stack has proved to be a cash cow for Google:[36]

Fig. 2

Google has constructed this money-grabbing structure through monopolistic practices, which, in turn, have reaped significant harm on advertisers, publishers, and the industry at large. DOJ alleges that Google has disrupted the sale of inventory, reduced publishers’ profits, harmed advertisers’ and publishers’ profitability by producing lower-quality transactions, and restricted choice and innovation throughout the ad tech stack.[37] The Complaint also lists the United States as an advertiser harmed by Google’s anticompetitive conduct, alleging that United States departments and agencies, including the Army, have incurred monetary damages as a result of Google’s conduct.[38] Though the overarching purpose of the Sherman Act is to protect consumers,[39] DOJ failed to identify specific harm to consumers or the general public, beyond stating that “Google’s anticompetitive acts have had harmful effects on competition and consumers.”[40] The Complaint briefly alludes to publishers’ increased use of subscriptions, paywalls, and alternative forms of monetization,[41] which potentially harm consumers by reducing access to information and Internet services. However, the Complaints fails to develop this connection between website monetization and consumer harm; rather, the emphasis is on the publishers’ ability to remain profitable through advertising alone.[42] Nevertheless, given that anticompetitive practices arguably always harm consumers, DOJ’s allegations may be sufficient.

As to remedies, DOJ seeks a judgment decreeing that Google violated the Sherman Act, damages to the United States for the monetary damages it incurred, the “divesture of, at minimum, the Google Ad Manager suite” (which includes DFP and AdX), and an injunction against further anticompetitive practices.[43]

Google’s anticompetitive practices described in this blog barely scratch the surface of DOJ’s claims. DOJ alleges a systemic, intentional takeover of the ad tech stack, characterized by tactful acquisitions, exploitation of Google’s customers and consumers, and secret projects that further entrenched Google’s monopoly. For example, in 2014, the Complaint describes ‘Project Bell,’ which lowered advertisers’ bids, without advertisers’ permission, to publishers who partnered with Google’s competitors.[44] Project Bell demonstrates the extent of Google’s anticompetitive scheme, which somehow thwarted the Federal Trade Commission (the agency charged with enforcing the Sherman Act, along with DOJ)[45] for nearly two decades.

When Google laid the first brick in its monopoly by acquiring DoubleClick (DFP and AdX), the FTC investigated but ultimately failed to challenge the acquisition, concluding that DFP’s sixty percent market share was insufficient to pose a risk of monopoly.[46] Had the FTC pursued its initial investigation, Google’s chokehold on digital ad tech may have been avoided. Nevertheless, the FTC’s failure to act likely gave Google the confidence to openly flaunt its unlawful practices, providing DOJ with ample evidence to bring the Sherman Act down on its monopoly.

[1] Ryan Holmes, We Now See 5,000 Ads A Day . . . And It’s Getting Worse, LinkedIn (Feb. 19, 2019), https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/have-we-reached-peak-ad-social-media-ryan-holmes/.

[2] Felix M. Simon & Lucas Graves, Reuters Inst. for the Study of Journalism, Pay Models for Online News in the US and Europe: 2019 Update 1 (May 2019), https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2019-05/Paymodels_for_Online_News_FINAL_1.pdf (finding that almost 70% of publishers in Europe and the US operate some form of paywall).

[3] Complaint at 118–19, United States v. Google, No. 00-108 (E.D. Va. filed Jan. 24, 2023).

[4] Id. at 132-39.

[5] Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1–38.

[6] Complaint, supra note 3, at 117.

[7] Id. at 3.

[8] Damien Geradin & Dimitrios Katsifis, Tilburg University, Google’s (Forgotten) Monopoly – Ad Technology Services on the Open Web 3 (May 21, 2019), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3391913#.

[9] Id.

[10] Id.

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Id. at 3–4.

[15] Complaint, supra note 3, at 16 fig. 2.

[16] Id. at 32.

[17] Id. at 45.

[18] Id. at 19–20.

[19] Id. at 18.

[20] Id. at 132–39.

[21] 15 U.S.C. § 1.

[22] Complaint, supra note 3, at 138–39.

[23] N. Pac. Ry. Co. v. U.S., 356 U.S. 1, 5–6 (1958).

[24] Complaint, supra note 3, at 138.

[25] Id.

[26] Id.

[27] Id. at 43–44.

[28] See, e.g., id. at 138 (alleging that “Google’s exclusionary conduct lacks a procompetitive justification”).

[29] 15 U.S.C. § 2.

[30] Complaint, supra note 3, at 132-39.

[31] Id.

[32] Id. at 133, 135, 137.

[33] Id. at 22.

[34] Id.

[35] Id. at 23.

[36] Id. at 23 fig. 4.

[37] Id. at 133, 135, 137.

[38] Id. at 123.

[39] Robert H. Bork, Legislative Intent and the Policy of the Sherman Act, 9 J.L. & Econ. 7, 11 (1966) (arguing that “the legislative intent underlying the Sherman Act was that court should be guided exclusively by consumer welfare”).

[40] Complaint, supra note 3, at 138.

[41] Id. at 4, 119.

[42] Id. at 118-119 (alleging that, as a result of Google’s practices, advertisers purchase less inventory from “publishers that internet users rely upon to generate and disseminate important content, and ultimately fewer publishers are able to offer internet users content for free (without subscriptions, paywalls, or alternative forms of monetization)”).

[43] Id. at 138-39.

[44] Id. at 72.

[45] Federal Trade Commission, The Enforcers, https://www.ftc.gov/advice-guidance/competition-guidance/guide-antitrust-laws/enforcers.

[46] Federal Trade Commission, Federal Trade Commission Closes Google/Double Click Investigation (Dec. 20, 2007), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2007/12/federal-trade-commission-closes-googledoubleclick-investigation.