14 Wake Forest L. Rev. Online 124

Paul H. Robinson[1] & Jeffrey Seaman[2]

Introduction

Progressive criminal justice reform has gained remarkable power in recent years. A wave of laws, such as California’s Proposition 47,[3] has reduced the punishment for many crimes,[4] downgraded felonies to misdemeanors,[5] and decriminalized previous offenses.[6] Bail requirements have been all but eliminated in many jurisdictions.[7] Progressive prosecutors control half of America’s largest district attorney’s offices and are responsible for making prosecution decisions affecting 72 million Americans.[8] Prison abolitionism has moved from the academic fringe to the vanguard of a public decarceration movement that seeks to empty prisons to combat “mass incarceration.” Some of this success is understandable. At its best, progressive reform promised to replace an unjustly harsh “throw away the key” mentality with a concern for giving offenders appropriate sentences the community finds just. But in practice, progressive reformers have increasingly embraced a “throw away the lock” mentality that sees minimizing punishment as itself a positive good. Here, however, progressive reform has lost its way. Its shift from demanding just punishment to preferring little or no punishment damages justice, fairness, and equity—all values progressive reformers claim to champion.[9] If it is to ever achieve those goals, much less win over the majority of Americans, progressive criminal justice reform needs to embrace the value of just punishment. The progressive reform movement has struggled to formulate an effective message on crime because the anti-punishment philosophy it accepts[10] leaves no room for the basic human intuition that wrongdoing should be punished in proportion to its severity. Progressive reformers can and should argue about what constitutes a just punishment, but they need to stop their destructive and futile crusade to abolish it. Part I of this piece describes the origins of the anti-punishment movement, and Parts II and III examine its manifestations in the prison abolition and progressive prosecutor movements. Parts IV, V, and VI argue that anti-punishment policies undermine justice, fairness, and equity, and Part VII calls for progressive reformers to embrace the value of just punishment.

I. The Anti-Punishment Movement

The progressive crusade against punishment began, as many destructive movements do, with a development in academia. Around the middle of the twentieth century, liberal criminologists embraced a disease theory of crime under which it made no sense to punish the infected.[11] If crime was not a choice, the only moral course of action was to replace the barbaric notion of punishment with treatment for the individual criminal (rehabilitation) and vaccination for society (social programs).[12] Such reformers took for granted that the purpose of the criminal justice system is merely to reduce crime and that punishment is a backward and ineffective means of doing so.[13] As one progressive criminologist wrote, “[P]unishment is never fated to ‘succeed’ to any great degree.”[14] A society that “intends to promote disciplined conduct and social control will concentrate not upon punishing offenders but upon socializing and integrating young citizens.”[15]

This anti-punishment perspective stands in sharp contrast to what the vast majority of people throughout history believed: that a criminal’s willful violation of another’s rights creates a moral basis, or even a necessity, to restrict the wrongdoer’s rights.[16] Ordinary people have always understood proportionate punishment as morally deserved regardless of its effects on future crime rates. Treatment can and should supplement such morally deserved punishment, but it cannot replace punishment without the “justice” part of the justice system being lost in the public mind.

While the progressive anti-punishment philosophy took shape in the mid-twentieth century,[17] the massive crime wave starting in the 1960s[18] pushed policymakers in the opposite direction. Harsh drug penalties, crude mandatory minimums, and three-strikes laws sometimes sentenced criminals for utilitarian reasons like deterrence or incapacitating recidivists without regard to their individual moral blameworthiness.[19] For example, one felon received a mandatory life sentence for three felonies that amounted to stealing just $229 in total, with the constitutionality of the sentence affirmed by the Supreme Court.[20]

This utilitarian-inspired “lock ‘em up and throw away the key” reaction to the crime wave cleared the way for the progressive criminal justice movement’s initial success. As the crime wave receded in the early 2000s,[21] progressive reformers called for reducing punishments and prison populations.[22] The resulting progressive-inspired reforms were often necessary even from the perspective of deserved punishment. Many mandatory minimums have been repealed to allow for an offender’s individual circumstances to be considered in sentencing decisions.[23] Numerous harsh drug penalties have been reduced to ones more in keeping with the public’s view of the blameworthiness of drug usage.[24] Old three-strikes laws have been repealed or amended to make sure distinctions can be drawn between misdemeanants and murderers.[25] Of course, more can be done to ensure just sentencing in these areas, but progress has been considerable.

Unfortunately, many progressives were not satisfied with pushing these laudable reforms. Having helped swing the pendulum of punishment toward a more justified middle closer to community views on just sentencing, the logic of the anti-punishment movement inexorably forced its proponents to swing for the opposite extreme.

II. The Prison Abolition Movement

The most explicit manifestation of this extreme anti-punishment swing is the prison abolition movement—which contains the leading edge of progressive criminal justice activists. Consciously styling themselves after anti-slavery abolitionists,[26] prison abolitionists leave no room for doubting their anti-punishment agenda or the moral seriousness with which they take the task of freeing imprisoned offenders.[27] The movement seeks to end the use of all prisons for all offenders, at least in the long run—an aim tantamount to ending criminal punishment in practice, as the suggested alternatives are non-punitive, such as therapy and education.[28] As Dorothy Roberts expresses it, the goal is to “build a more humane, free, and democratic society that no longer relies on caging people to meet human needs and solve social problems.”[29]

Despite the obvious impracticality (not to mention injustice) of ending prison and punishment, the abolition movement has had substantial success at steering the conversation, at least among progressive reformers. The success of best-selling books like prison abolitionist Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow[30] has led to serious coverage of the movement in outlets including The New York Times,[31] The Guardian,[32] GQ,[33] and The New Yorker.[34] A growing contingent of progressive academics identify as prison abolitionists, and where academia leads, policymakers often follow.

The broader and more successful decarceration movement (which includes some voices not opposed to punishment, such as our own) is often spearheaded by prison abolitionists who see reducing prison populations as a step toward ending all prison in the future. Tellingly, such prison abolitionists in the decarceration movement seem more concerned with ending punishment itself than prison as a method of punishment. If anti-prison advocates are really concerned with simply ending prison, rather than as a means toward ending punishment, they should work harder to develop and implement more punitive forms of non-incarcerative sanctions that can safely and justly substitute for prison sentences in a wider range of criminal cases. Railing against the use of prison is not nearly as productive as finding alternative punishments that satisfy the public’s demand for justice while being cheaper and less likely to promote recidivism. Studies show ordinary people intuitively agree that the right combination of non-incarcerative sanctions can equal the punitive “bite” of many prison sentences.[35] For example, one study found that respondents perceived a (2023 inflation-adjusted) $50,000 fine as being more punitive than a one-year prison sentence (for certain offenders).[36] Meanwhile, weekends in jail, ISPs (intensive supervision programs), or home confinement for two years were seen as more punitive than six months in prison.[37] These findings show it is possible to construct scalable non-incarcerative punishments that would still be seen by the community as doing justice.[38] We have written elsewhere proposing such a justice-satisfying “electronic prison” scheme.[39]

But progressive reformers have shown little interest to date in pursuing these promising possibilities because they still involve punishment, and the philosophical underpinnings of progressive criminal justice reform oppose punishment.[40] Decarcerating while preserving punishment may be seen as preserving the “barbarity” of retribution—a barbarity that many progressive reformers would like to end once and for all. If punishment in response to crime is viewed as a kind of unjustifiable oppression,[41] simply switching the form of that oppression from a prison sentence to an equivalently punitive non-incarcerative sentence will still be viewed as unacceptable. Supporting sensible and productive replacements for prison sentences would also never allow prison abolitionists to reach their no-prison goal because the public will always see some of the most serious crimes as requiring incarceration. No amount of community service or intensive supervision on its own is going to be seen as a just punishment for murder.

Of course, many progressive reformers who hold anti-punishment views do not openly advocate for ending all punishment.[42] Targeting prison—rather than punishment itself—is a strategic rhetorical choice on the part of radical reformers who know their ultimate goal is unacceptable to the vast majority of people.[43] Such reformers presumably hope to use public dissatisfaction with the current prison system to implement decarceration policies that simply do away with punishment without the public noticing. Indeed, this can be seen in the policies pursued by the progressive prosecutor movement.

III. The Progressive Prosecutor Movement

Perhaps because they seek to win elections, progressive prosecutors often claim their goal is to use prosecutorial discretion to end overly punitive punishments, especially for minor crimes, and focus on punishing serious offenders with the saved resources.[44] Progressive prosecutors would be less controversial if they really did try to assign punishments based on what their community found just, including an increased focus on prosecuting severe crime. However, after promising to punish serious crime to win elections, such prosecutors commonly reveal their true priorities in office. Instead of trying to deliver punishments the community finds just, progressive prosecutors too often take a slash-and-burn approach to reducing prison populations by simply letting criminals go free. As progressive prosecutor Sarah George explains, “The most powerful thing that elected prosecutors can do is not charge.”[45] Progressive prosecutors repeatedly use prosecutorial discretion in quasi-legislative ways, employing non-prosecution policies to refuse to prosecute whole swaths of crime, systematically downgrade charges, drop cases, or cut lenient plea bargains that let serious criminals escape prison.[46] The rate at which progressive prosecutors have reduced prosecutions (and therefore punishment for criminality) is astonishing and deeply disturbing to those who still support punishing crime.

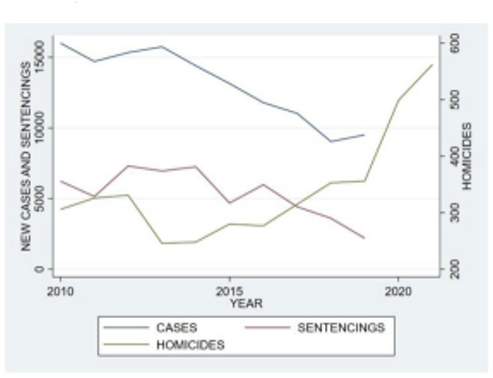

For example, consider how Philadelphia has fared in the years since progressive prosecutor Larry Krasner was elected in 2017. Krasner has filed the fewest criminal cases in Philadelphia’s modern history and reduced criminal sentencings by an astounding 70%.[47] Meanwhile, in what progressives maintain is surely a coincidence, homicides have reached the highest rate in Philadelphia’s history, up from 315 in 2017 to 562 in 2021—an increase of 78%.[48]

For example, consider how Philadelphia has fared in the years since progressive prosecutor Larry Krasner was elected in 2017. Krasner has filed the fewest criminal cases in Philadelphia’s modern history and reduced criminal sentencings by an astounding 70%.[47] Meanwhile, in what progressives maintain is surely a coincidence, homicides have reached the highest rate in Philadelphia’s history, up from 315 in 2017 to 562 in 2021—an increase of 78%.[48]

Krasner’s office dropped 65% of gun charges in 2021,[49] despite the fact Philadelphia was suffering a surge in shootings caused by criminals carrying guns on the street.[50] Krasner’s prioritization of reducing prison populations above punishing and preventing serious crime may seem strange to those who do not share his anti-punishment philosophy, but when punishment itself is viewed as the problem to be solved, Krasner becomes a hero of the oppressed lawbreaker.

Krasner’s duplicitous promise to focus on just punishments and serious crime only to pursue decarceration by any means is hardly unique among progressive prosecutors. Similar patterns of decreased prosecution amid increasing crime have been observed in a wide range of jurisdictions helmed by progressive DAs. In Dallas, guilty verdicts for felonies decreased by a dramatic 30% after John Creuzot assumed office.[51] In Chicago, Kim Foxx dismissed charges against nearly 30% of felony suspects,[52] while suffering a 50% increase in homicides in 2020. Progressive prosecutors have also routinely decriminalized entire classes of crime even against community wishes. San Francisco’s Chesa Boudin did not secure a single conviction for dealing fentanyl during 2021,[53] even though San Francisco was in the midst of a surging fentanyl crisis that killed nearly 500 people the year before.[54]

Progressive DAs have also consistently downgraded the punishment of a wide variety of crimes without any consideration of community views. Even in the face of violent crime rates stuck at high levels[55] and citizens clamoring for punishment and protection,[56] Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg announced his intention to downgrade felony charges in cases including armed robberies and drug dealing and declared he will “not seek a carceral sentence other than for homicide” or a “class B violent felony” with few exceptions.[57] Some progressive DAs have even discouraged crime victims from turning to the justice system, believing that prosecution and punishment is not an appropriate response. Former Virginia Commonwealth Attorney Buta Biberaj believed most domestic abuse victims should seek help through social services as opposed to pursuing a criminal complaint.[58] Unsurprisingly, she dropped 66% of domestic violence cases, leading to community dissatisfaction and her ouster from office in 2023, an otherwise excellent election cycle for Virginia Democrats.[59]

The actions of progressive prosecutors often appear baffling and could easily be misinterpreted as incompetence if not for the unifying thread running through all their decisions: send as few criminals to prison as possible for as little time as possible. It would be insulting to DAs like Krasner and Bragg to suggest they do not understand their own actions. Rather, they see reducing or eliminating punishment through their policies as wholly appropriate because it is, at least within the context of their anti-punishment ideology. Such prosecutors understand they cannot release all criminals, as they might wish in the utopian future of the prison abolitionists, but they can release far more criminals than any of their predecessors, thus sparing thousands of oppressed offenders the further predations of the justice system. To those who believe in the value of deserved punishment, however, the anti-punishment actions of progressive prosecutors seem at best a dereliction of duty and at worst a malign assault on society. This is especially the case since the vast majority of serious crime already goes unpunished in the current system—more than half of murderers and more than nine out of ten robbers, rapists, and assaulters escape punishment for their crimes.[60] In light of this crisis of under-punishment, releasing even more offenders appears shockingly negligent. But when criminal punishment is equated with societal oppression, releasing as many criminals back onto the streets as possible becomes a bold act of social justice. What is lost, however, is individual justice.

IV. Justice Problems: The Futility of Fighting Human Nature and the Detrimental Consequences of Doing So

Are progressives right to embrace the anti-punishment movement? What is lost by turning punishment into a problem to be solved rather than a just sentence to be served? The answer is justice, fairness, and equity—all values progressives should support.

First, opposing punishment is destructive because a non-punitive approach fails to do justice, regardless of whether one believes a “just” system requires punishment as a matter of morality or whether it merely requires controlling crime in the long run (which anti-punishment advocates believe can be done through non-punitive, therapeutic interventions). Attempting to minimize criminal punishment is obviously unjust from the perspective of “just deserts”—a belief that criminals morally require punishment proportional to their wrongdoing. Inconveniently for progressive reformers, this view of justice is a fundamental part of human nature and is supported by the vast majority of people regardless of time period or culture.[61] The empirical proof of this fact is overwhelming. Cross-cultural studies and laboratory experiments reveal humans’ deep-seated desire to punish what they perceive as wrongdoing against either themselves or others, even if it requires sacrifice on their part. Consider just one example, the so-called Ultimatum Game, a study that tests people’s willingness to punish perceived wrongdoing.[62] In the game, two participants are randomly assigned to be a “Proposer” or “Responder.”[63] The Proposer is provisionally given a sum of money, called an “Endowment,” often ten dollars, to split between himself and the Responder.[64] If the Responder accepts the suggested split, both walk home with the divided money.[65] If the Responder rejects, they both get nothing.[66] Proposers are typically quite fair, offering between 40% and 50% of the Endowment to Responders,[67] even though from a perspective of pure self-interest they should only offer one dollar to the Respondent, who is still better off accepting versus walking away with nothing. But in fact, when Proposers suggest highly unjust splits giving the Responder only 10%, 20%, or 30% of the endowment, Responders usually reject the proposal, forfeiting the money they could have gained in order to punish the perceived wrongdoing of the Proposer.[68] This decision to punish contrary to self-interest happens under carefully controlled conditions, when the subjects do not physically interact with one another, do not know one another’s identities, and when even the experimenter does not know the Responder’s decision.[69] Even more striking, third-party observers with no stake in the game will themselves pay to punish Proposers they perceive as behaving intentionally unfairly towards Responders.[70]

And this desire to punish is not socially learned. Studies have shown that even preverbal infants display a desire to punish offenders in cases where they have no personal stake in the interaction—demonstrating just how deep and instinctual the human desire for just punishment is.[71] The fact that humans of all ages will sacrifice their own interests to punish offenders in unrelated cases is indisputable. As several scholars note, the evidence for the human desire to punish offenders “is so universal and robust that it does not require any more replication studies.”[72]

Importantly, this ingrained desire to punish reflects a moral belief in the value of doing justice, not merely utilitarian considerations such as preventing future crime. Studies examining whether ordinary people assign criminal punishments on the basis of desert (the blameworthiness of the individual offender) or deterrence and incapacitation (promoting crime control) have consistently shown that people choose to punish based on desert.[73] Although people certainly support deterring future crime and incapacitating dangerous criminals as goals of the justice system,[74] furthering these goals is not enough to meet the human demand for justice. Even if—and it is a very large and dubious if—progressive reformers could provide non-punitive means that were as or more effective at controlling crime than punishment, it would not satisfy the human demand for justice. If a serial killer were made harmless through the ministrations of a personal therapist, almost everyone would still demand he be punished even though he posed no further threat to society. To the extent that any moral principles are hardwired into humans, a demand for just punishment is one of them.

But perhaps, as some progressives believe, the innate human desire for proportionate punishment is simply wrong, and we can use our rational brains to make moral progress by building a criminal justice system without punishment that still controls crime. This certainly appears to be the vision of Dorothy Roberts, the prison abolitionist quoted previously.[75] But it is impossible. Even if a non-punitive justice system could succeed in theory (in that it controls crime as effectively as just punishment would), it would still fail in practice because a justice system that flouts the (even mistaken) moral intuitions of its citizens erodes the moral credibility of the law and inspires crime. The empirical and historical evidence is clear: the crime control effectiveness of a justice system increases as its reputation for doing justice as the community sees it increases.[76] The more the system is perceived as failing to do justice, the more it will “provoke resistance, subversion, and vigilantism”—even if society’s elites believe it to be superior.[77] Even small incremental losses in the system’s moral credibility with the public can produce corresponding losses in compliance with the law.[78] This is both because people will believe they can get away with breaking the law and because the stigma of breaking the law is reduced as the legal system loses moral authority for failing to deliver the community’s understanding of justice. This dynamic helps explain the vicious cycle communities with high crime and low rates of punishment experience—many residents observe the legal system as failing to do justice (i.e., punish lawbreakers) and consequently do not see the law as worthy of respect or compliance.

So even if we accept—contrary to human nature—that a non-punitive justice system that controlled crime would be morally just, it would still be impossible to remove punishment from the system. Even if non-punitive therapy stopped individual criminals from reoffending, the overall loss in credibility a punishment-free legal system would experience would replenish the ranks of new offenders. Until the community actually believes criminals should not be punished (and there has been no progress at rooting out this deep human desire), it will be impossible to achieve “justice” in either the way most humans understand it (which requires punitiveness) or even as some utilitarians understand it (simply controlling crime) without resorting to retribution.

Perhaps the clear necessity of retributive punishment to satisfy public demands—even from a utilitarian perspective—explains why the American Law Institute amended its Model Penal Code, which is the foundation for criminal codes in three-quarters of U.S. states, in 2007 to set desert (punishing offenders in proportion to their blameworthiness) as the dominant, inviolable distributive principle over all other principles for distributing punishment.[79] Deterring, incapacitating, and rehabilitating criminals are all worthy goals, but they should be pursued within the framework of delivering a punishment the community agrees is just. The progressive push to do away with punishment, or at least reduce it far below a level the community would find just, is a push against human nature that is bound to fail, but not before it does real harm to the moral credibility of the law and invites the increased crime such damage causes.

V. Fairness Problems: Fair Notice, Consistency, and Equal Treatment Under the Law

In addition to damaging the delivery of justice, progressive reforms often damage the fundamental notions of fairness that underpin the legal system. American criminal law is built on the legality principle, which requires a prior clear and specific written legislative statement of what is criminal, in order to give fair notice and guarantee people will be treated equally under the system—the “rule of law” rather than the “rule of the individual.”[80] Fair notice is important not only so people can avoid criminal behavior, but also to maximize liberty by avoiding gray areas where uncertainty may discourage people from engaging in lawful conduct. Clarity and consistency in application also means that powerful officials, like judges or prosecutors, cannot arbitrarily find their own personal or political reasons to punish—or not punish—individuals. It is also basic fairness that the same standard of criminal behavior and punishments should apply to all people within the same jurisdiction. While some discretion in charging and sentencing is certainly necessary for prosecutors and judges to distinguish the special circumstances of an individual case from those of other cases, this discretion should only operate to decide how a specific criminal relates to the governing law, not grant the power to rewrite the law. For example, a prosecutor might legitimately use their discretion to charge a specific robber carrying a holstered gun with simple robbery instead of armed robbery if the defendant in question did not act like other armed robbers by directly threatening the victim with the weapon. By contrast, instituting a policy of charging all robbers with only a lesser charge of theft reflects a desire to override the democratically enacted criminal law, not an exercise of discretion to account for special circumstances.

When progressive reformers change the criminal law through a state’s normal democratic processes, fairness is not undermined no matter how unwise or destructive the legal change. However, when anti-punishment prosecutors decarcerate criminals by abusing prosecutorial discretion, their actions undermine the legality principle’s promise of fair notice and equal treatment, creating a deeply unfair rule of the individual as opposed to the rule of law.

First, the ad hoc decriminalization and decarceration decisions made by progressive prosecutors undermine equal treatment by creating an enormous potential for gross disparities in the application of the same state law for similar offenders committing similar offenses, with only a county line between the crimes. For example, San Francisco’s progressive former DA, Chesa Boudin, chose to de facto decriminalize shoplifting by refusing to bring charges against such theft.[81] While Boudin’s actions kept criminals out of jail, they created clear unfairness by creating an arbitrary difference in the way criminals were treated under the same state law based on city borders. The abuse of discretion by progressive prosecutors also creates unfairness to residents. While burglaries fell nationwide in 2020, they surged by almost 50% in San Francisco.[82] Walgreens was forced to close 22 stores in the city due to squads of shoplifters cycling in and out.[83]

A thief who stole from a store in Boudin’s jurisdiction could reasonably expect no punishment and store owners could reasonably expect no protection, while the opposite could be true of a thief who stole from another store a few thousand feet away in a different DA’s jurisdiction. The thief who is punished might rightly wonder why the legal system treats his behavior so much more severely when he committed the same action as the thief nearby who received no punishment. By the same logic, a store owner in San Francisco might rightly wonder why they receive no protection when a nearby store does.

The state law is meant to protect and punish equally across the state, but patchwork decriminalization by progressive prosecutors means both law-abiding citizens and criminals will receive vastly different treatment based on the whims of individual prosecutors. The only fair way for anti-punishment advocates to achieve their goal is to undertake the normal democratic process of changing the state’s criminal law—or, at the very least, persuading the legislature that local jurisdictions ought to be delegated full criminalization authority. But progressive reformers often opt for local change because it is hard to pass anti-punishment laws when a majority of people in every state do not fundamentally oppose punishment. It is far easier to win local elections in highly partisan districts. As a result, progressive prosecutors routinely adopt a deeply unfair and anti-democratic work-around to changing the law by abusing their prosecutorial discretion instead.

A second unfairness is that when the de facto criminal law of a jurisdiction changes through the individual whim of the prosecutor, it erodes the legality principle by making it unclear what conduct is in practice criminal and what the punishment for legally defined crimes will be. The de facto law even within the same county is subject to change without notice as progressive prosecutors adjust their charging decisions based on the political climate or an election that ushers in a new prosecutor with different political views. The result is often a massive change in the treatment of citizens in the same place even with no change in law—the very definition of the “rule of the individual” as opposed to the rule of law. For example, the results of Boudin’s policies proved so unpopular even in progressive San Francisco that he was recalled from office in June 2022 and replaced by a new prosecutor more willing to prosecute and jail offenders.78 Once again, the state of the law became unclear to residents. Was theft punishable again? Would the same actions that one day brought no punishment suddenly bring punishment again the next day because a new person sat in the prosecutor’s office? Only extreme partisanship can blind one to the fundamental arbitrariness created by progressive reformers’ slash-and-burn approach to reducing punishment regardless of statutory law. Regardless of their intentions, progressive prosecutors’ abuse of discretion to confusingly bend the criminal law back and forth damages the principles of fairness upon which the American justice system is built.

VI. Equity Problems: Making the Poorest and Most Vulnerable Bear the Cost of Progressive Social Experimentation

An argument commonly made in defense of progressive criminal justice reforms is that one cannot make an omelet without breaking a few eggs. As Milwaukee’s progressive DA, John Chrisholm, explained, “Is there going to be an individual that I divert, or I put into treatment program, who’s going to go out and kill somebody? You bet. Guaranteed. It’s guaranteed to happen. It does not invalidate the overall approach.”[84] (Incidentally, Darrel Brooks, the man who massacred six people at a Christmas Parade in Wisconsin was indeed released by Chrisholm’s office despite violently assaulting the mother of his child and having a long history of serious crime.)[85] Such reasoning holds that a temporary rise in victimizations now is a worthwhile price to advance the anti-punishment cause, free oppressed criminals, and ultimately usher in a better future with less crime for all.[86] While non-progressives may protest at the prospect of eggs being broken for what looks to them like a grease fire rather than an omelet, even if we accept the claim that temporary additional victimizations are necessary to produce a better future, there is still the problem of who bears that cost. While progressives are devoted to discovering and combatting real or imagined disparities in the justice system’s treatment of racial minorities, they appear stunningly uncurious about the impact of their anti-punishment policies on crime in minority communities. The stark truth is that indiscriminately releasing criminals without punishment—often justified by the claim it is reducing the racial injustice of “mass incarceration”—is directly and disproportionately fueling victimizations in minority communities, thus making society less equitable. Why should the most vulnerable in society pay the current costs of building what reformers hope will one day be a better society? Progressive reformers would like to deny or ignore this problem, but they cannot if they wish to take equity seriously.

All crime, especially violent crime, affects poor and minority communities the most. First, the violent crime rate is disproportionately higher in poor neighborhoods,[87] and the people who live in those areas are often racial minorities.[88] For example, the Department of Justice found that from 2008 through 2012, Americans living in households at or below the Federal Poverty Level had more than double the rate of violent victimization as persons in higher-income households.[89] In 2020, Blacks suffered the highest rate of violent victimization of any racial group.[90] Police also solve crimes less often in minority neighborhoods. For example, police in Chicago have historically solved homicide cases involving a White victim 47% of the time, cases involving a Hispanic victim 33% of the time, and cases involving a Black victim 22% of the time.[91] Any policies that release offenders back into the high-crime communities they victimize are likely to lead to additional strings of unsolved crimes affecting poor and minority residents. Crime surges always affect minority communities the worst. For example, the recent murder surge starting in 2020 has been mainly driven by Black victims, with the murder rate for White victims increasing by 0.4 per 100,000 between 2018 and 2021, while the rate for Black victims increased by 9.7 per 100,000—25 times more than for White victims.[92] A Washington Post investigation of murder trends in several large cities found that “Black people made up more than 80 percent of the total homicide victims [in those cities] in 2020 and 2021,”[93] and most of these murders have gone unsolved. When progressive DAs like Manhattan’s Alvin Bragg “break eggs” in the form of allowing offenders to go unpunished and revictimize their communities, they are forcing minority communities to bear the brunt of the pain. In 2021, 97% of shootings in New York City were of Blacks or Hispanics.[94]

Minority communities have noticed the lack of concern from progressive reformers. Even as violence surged in Philadelphia’s minority neighborhoods, Philadelphia’s progressive DA stated the city did not have a “crisis of crime” or a “crisis of violence”—statements that he ultimately was forced to walk back even as he continued dropping thousands of cases.[95] Of course, in the gated communities where elite progressives often live, there is little need to worry about crime. The reality for ordinary citizens is different. Former Philadelphia mayor Michael Nutter, who is Black, excoriated Krasner by arguing if the DA “actually cared about [Black and Latino communities], he’d understand that the homicide crisis is what is plaguing us the most.”[96]

If progressives are to preserve their commitment to equity in the criminal justice system, they must recognize that releasing criminals without punishment will inevitably make society less equitable in terms of criminal victimization. The excuse that imprisoning Black or Latino offenders is somehow more damaging to equity is to make the appalling (not to mention racist) assumption that the interests of minority communities are chiefly represented by the welfare of lawbreakers and not the majority of law-abiding residents prone to be victimized. Releasing minority offenders to revictimize minority residents does not advance racial justice. Too often the same advocates who protest against police violence and decry the injustices caused by “systemic racism” in the legal system are nowhere to be found on the issue of decreasing crime in minority communities. As argued previously,[97] anti-punishment policies will not decrease crime in the long run, but even if they did, it would be essential to ensure their short-term costs were not borne disproportionately by the most disadvantaged members of society. One might expect progressives to pair anti-punishment policies with heightened police protection for minority neighborhoods. Of course, the contrary often occurs, with progressives advocating less police presence even while releasing more offenders. Unfortunately, it appears that solipsistic self-congratulation, rather than promoting actual equity, has become a motivation for criminal justice policy among too many progressive reformers.

VII. The Future of Progressive Criminal Justice Reform

Progressive criminal justice reform, guided by anti-punishment principles, has mistakenly embraced policies aimed at reducing the justice system’s power to control or punish criminals. Whether it is ending bail requirements without suitable alternatives,[98] dropping charges against clearly guilty offenders,[99] downgrading felonies to misdemeanors,[100] or reducing police funding, progressive criminal justice reform undoubtedly deserves its perception among non-progressives as “soft on crime.” The negative consequences of these reforms have led to widespread backlash and the reversal of numerous progressive policies. Bail reform has been walked back in many jurisdictions, including New York.[101] Progressive prosecutors have been voted out of office, like Chesa Boudin[102] or Buta Biberaj,[103] or they have resigned under pressure like Kim Gardner.[104] States have moved to reverse poorly considered progressive decriminalizations, with California preparing to tighten laws against theft[105] and Oregon recriminalizing hard drugs.[106] Jurisdictions and policymakers that previously championed defunding the police in favor of social services have admitted their mistakes and called for more police funding.[107] This backtracking is a tacit admission of failure as well as evidence that such policies are politically infeasible in the long run. Many Democratic officials have come to understand that opposing punishment is an unwise decision from a policy and electoral standpoint. Democratic mayors, legislators, governors, and even President Joe Biden have all spoken about the need for taking crime more seriously—through enforcing the law and punishing crime.[108] The question is whether progressive reformers will listen to the legitimate criticisms of their policies coming from the left, right, and center. Heeding such criticism does not mean giving up on the noble goals of progressive reform. There is nothing wrong with progressives wanting to stop crime at its roots through social programs or desiring to improve treatment and training programs available to offenders. There is nothing wrong with desiring to reduce jail and prison populations or working to decriminalize behavior the community no longer sees as condemnable. The problem is when progressives pursue their goals by ignoring the community’s demand for imposing just punishment on criminals. Progressives need to embrace a punishment-and-reform instead of a punishment-or-reform perspective if they wish to achieve lasting success.

The anti-punishment movement, including its manifestations in the prison abolition and progressive prosecutor movements, is a dead-end for progressives. Real criminal justice reform needs to embrace punishment—as paradoxical as it may sound to progressives—to succeed at advancing justice, fairness, and equity. Its rallying cry should be “just punishment for all” not “no punishment for most.” Instead of subverting criminal codes with non-prosecution, it should gain support for changing statutory punishments to ones in line with public views on what constitues appropriate punishment. Instead of thoughtlessly slashing prison populations, it should seek to impose just non-incarcerative punishments and reform the nature of prison to make it less damaging to offenders. Instead of fighting punishment, those of all political affiliations need to fight injustice—including the failure to punish crime.

- . Paul H. Robinson is the Colin S. Diver Professor of Law at the University of Pennsylvania. ↑

- . Jeffrey Seaman holds a Master of Science in Behavioral and Decision Sciences from the University of Pennsylvania and is a Levy Scholar at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. ↑

- . Safe Neighborhoods and Schools Act (Proposition 47), 2014 Cal. Legis. Serv. 47 (codified at Cal. Penal Code § 1170.18). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Theodora Koulouvaris, How Have Other States Implemented the Near Elimination of Cash Bail?, WCIA (Jan. 26, 2023), https://www.wcia.com/news/how-have-other-states-implemented-the-near-elimination-of-cash-bail/. ↑

- . Josh Christensen, Report: Soros Prosecutors Run Half of America’s Largest Jurisdictions, Wash. Free Beacon (June 8, 2022), https://freebeacon.com/democrats/report-soros-prosecutors-run-half-of-americas-largest-jurisdictions/. ↑

- . Candace Smith et al., Progressive Prosecutors Aim to Change the Criminal Justice System from the Inside, ABC News (Oct. 1, 2020), https://abcnews.go.com/US/progressive-prosecutors-aim-change-criminal-justice-system-inside/story?id=73371317. ↑

- . Paul H. Robinson & Joshua Crawford, Opinion, Progressive Prosecutors and the Inconvenient Democratic Will, Newsweek (May 5, 2023), https://www.newsweek.com/progressive-prosecutors-inconvenient-democratic-will-opinion-1798165. ↑

- . See, e.g., Francis T. Cullen, Rehabilitation: Beyond Nothing Works, in 42 Crime and Justice in America 1975–2025, at 299, 308–12 (Michael Tonry ed. 2013). ↑

- . See id. at 309. ↑

- . See, e.g., id. at 313. ↑

- . David Garland, Punishment and Modern Society 289 (1990). ↑

- . Id. at 292. ↑

- . Daniel McDermott, The Permissibility of Punishment, 20 L. & Phil. 403, 404 (2001). ↑

- . Joshua Kleinfeld, Two Cultures of Punishment, 68 Stan. L. Rev. 933, 1030 (2016). ↑

- . Barry Latzer, The Rise and Fall of Violent Crime in America 110 (2016). ↑

- . Joe D. Whitley, Three Strikes and You’re Out: More Harm Than Good, 7 Fed. Sent’g Rep. 64 (1994); Kleinfield, supra note 17, at 933. ↑

- . Rummel v. Estelle, 445 U.S. 263, 285 (1980). ↑

- . Maria Kaylen et al., The Impact of Changing Demographic Composition on Aggravated Assault Victimization During the Great American Crime Decline: A Counterfactual Analysis of Rates in Urban, Suburban, and Rural Areas, 42 Crim. Just. Rev. 291, 296 (2017). ↑

- . See Dorothy E. Roberts, Abolition Constitutionalism, 133 Harv. L. Rev. 1, 115 (2019). ↑

- . See id. at 115–16, 116 n.719. ↑

- . See id. at 115–17, 116 n.721; U.S. Sent’g Comm’n, Retroactivity & Recidivism: The Drugs Minus Two Amendment 1 (2020). ↑

- . See David Mills & Michael Romano, The Passage and Implementation of the Three Strikes Reform Act of 2012 (Proposition 36), 25 Fed. Sent’g Rep. 265, 265 (2013); Apoorva Joshi, Explainer: Three Strikes Laws and Their Effects, Interrogating Justice (July 23, 2021), https://interrogatingjustice.org/mandatory-minimums/three-strikes-laws-and-effects/. ↑

- . Roberts, supra note 22, at 4–5, 5 n.17. ↑

- . See id. at 4–5, 5 n.17, 8. ↑

- . See id. at 43–44. ↑

- . Id. at 12. ↑

- . See generally Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow (2010). ↑

- . See, e.g., Rachel Kushner, Is Prison Necessary? Ruth Wilson Gilmore Might Change Your Mind, N.Y. Times Mag. (Apr. 17, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/17/magazine/prison-abolition-ruth-wilson-gilmore.html. ↑

- . See, e.g., Joshua Dubler & Vincent Lloyd, Think Prison Abolition in America is Impossible? It Once Felt Inevitable, Guardian (May 19, 2018), https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/may/19/prison-abolition-america-impossible-inevitable. ↑

- . See, e.g., Gabriella Paiella, How Would Prison Abolition Actually Work, GQ (June 11, 2020), https://www.gq.com/story/what-is-prison-abolition. ↑

- . See, e.g., Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, The Emerging Movement for Police and Prison Abolition, New Yorker (May 7, 2021), https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/the-emerging-movement-for-police-and-prison-abolition. ↑

- . See Robert E. Harlow et al., The Severity of Intermediate Penal Sanction: A Psychophysical Scaling Approach for Obtaining Community Perceptions, 11 J. Quantitative Criminology 71, 71–89 (1995). ↑

- . Id. at 85. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. at 89. ↑

- . Paul H. Robinson & Jeffrey Seaman, Electronic Prison: A Just Path to Decarceration, (Univ. of Penn. L. Sch. Pub. L. and Legal Theory Rsch. Paper Series, Paper No. 24-20) (forthcoming 2025), https://ssrn.com/abstract=4808818. ↑

- . See id. at 7. ↑

- . See id. at 18. ↑

- . See id. at 7. ↑

- . See id. at 7. ↑

- . See Platform, Larry Krasner for District Attorney, https://krasnerforda.com/platform (last visited Nov. 1, 2024) (Larry Krasner’s platform promising this). ↑

- . Meet the Movement/Voices of Change, Fair & Just Prosecution, https://fairandjustprosecution.org/movement/voices-of-change/ (last visited Nov. 1, 2024). ↑

- . See Thomas P. Hogan, De-prosecution and Death: A Synthetic Control Analysis of the Impact of De-prosecution on Homicides, 21 Criminology & Pub. Pol’y 489, 490 (2022). ↑

- . Id. at 499. ↑

- . See id. at 500. ↑

- . The Editors, To Stop Philly’s Cycle of Violence, D.A. Krasner Must Prosecute Gun Crimes, Broad & Liberty (Aug. 8, 2021), https://broadandliberty.com/2021/08/08/stop-phillys-cycle-of-violence-d-a-krasner-must-prosecute-gun-crimes/. ↑

- . See id. ↑

- . L. Enf’t Legal Def. Fund, Prosecutorial Malpractice (2020), https://www.policedefense.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Prosecutorial-Malpractice.pdf. ↑

- . Charles D. Stimson & Zach Smith, “Progressive” Prosecutors Sabotage the Rule of Law, Raise Crime Rates, and Ignore Victims, Heritage Found. (Oct. 29, 2020), https://www.heritage.org/crime-and-justice/report/progressive-prosecutors-sabotage-the-rule-law-raise-crime-rates-and-ignore. ↑

- . Anna Tong & Josh Koehn, DA Boudin and Fentanyl: Court Data Shows Just 3 Drug Dealing Convictions in 2021 as Immigration Concerns Shaped Policy, S.F. Standard (May 17, 2022), https://sfstandard.com/criminal-justice/da-chesa-boudin-fentanyl-court-data-drug-dealing-immigration/. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . See Despite Recent Uptick, New York City Crime Down from Past Decades, Reuters (Apr. 13, 2022), https://www.reuters.com/world/us/despite-recent-uptick-new-york-city-crime-down-past-decades-2022-04-12/. ↑

- . See Fear of Rampant Crime is Derailing New York City’s Recovery, Bloomberg (July 29, 2022), https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2022-is-nyc-safe-crime-stat-reality/. ↑

- . See Brittany Bernstein, New Manhattan DA Walks Back Memo Claiming Decriminalization ‘Will Make Us Safer,’ Nat’l Rev. (Jan. 20, 2022), https://www.nationalreview.com/news/new-manhattan-da-walks-back-memo-claiming-decriminalization-will-make-us-safer/. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Matt Palumbo, George Soros Spent $40M Getting Lefty District Attorneys, Officials Elected All Over the Country, N.Y. Post (Jan. 26, 2023), https://nypost.com/2023/01/22/george-soros-spent-40m-getting-lefty-district-attorneys-officials-elected-all-over-the-country/. ↑

- . In 2006, the last year state homicide conviction data was published, only 36% of murders ended in a homicide conviction. The number is likely lower today due to falling clearance rates since 2006. See Sean Rosenmerkel et al., U.S. Dep’t of Just., Bureau of Just. Stat., Felony Sentences in State Courts, 2006—Statistical Tables (2010), https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/fssc06st.pdf. For statistics on rape, robbery, and assault, see The Criminal Justice System: Statistics, RAINN, https://www.rainn.org/statistics/criminal-justice-system (last visited Nov. 1, 2024). ↑

- . See Mathias Twardawski et al., What Drives Second- and Third-Party Punishment? Conceptual Replications of the Intuitive the “Intuitive Retributivism Hypothesis, 230 Zeitschrift für Psychologie 77, 77 (2022). ↑

- . See Gary E. Bolton & Rami Zwick, Anonymity Versus Punishment in Ultimatum Bargaining, 10 Games & Econ. Behav. 95, 95–96 (1995). ↑

- . Colin Camerer, Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments in Strategic Interaction 48 (2003). ↑

- . See Bolton & Zwick, supra note 62, at 96. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . This varies considerably depending on the details of the experimental procedure. See Camerer, supra note 63, at 49–52. ↑

- . Id. at 49–54. ↑

- . See Bolton & Zwick, supra note 62, at 111 (showing that punishment occurs even when experimenters do not know subjects’ decisions). ↑

- . Daniel Kahneman et al., Fairness and the Assumptions of Economics, 59 J. Bus. S285, S288–91 (1986). ↑

- . Yasuhiro Kanatogi et al., Third-Party Punishment by Preverbal Infants, 6 Nature Hum. Behav. 1234, 1239 (2022); Katherine McAuliffe et al., Costly Third-Party Punishment in Young Children, 134 Cognition 1, 8 (2015). ↑

- . Twardawski et al., supra note 61. ↑

- . Kevin M. Carlsmith et al., Why Do We Punish? Deterrence and Just Deserts as Motives for Punishment, 83 J. Personality & Soc. Psych. 284, 289 (2002). ↑

- . See id. ↑

- . Roberts, supra note 22, at 7–8. ↑

- . Paul Robinson et al., The Disutility of Injustice, 85 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1940 (2010). ↑

- . Paul Robinson & Lindsay Holcomb, The Criminogenic Effects of Damaging Criminal Law’s Moral Credibility, 31 S. Cal. Interdisc. L.J. 277 (2022). ↑

- . Robinson et al., supra note 76, at 2013. ↑

- . Paul Robinson & Tyler Scot Williams, Mapping American Criminal Law: Variations Across 50 States, at 8 (2018). ↑

- . See Paul H. Robinson et al., Rethinking the Balance of Interests in Non-Exculpatory Defenses, 114 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 1, 41–42 (2024). ↑

- . See Michael Barba, Data Shows Chesa Boudin Prosecutes Fewer Shoplifters Than Predecessor, S.F. Exam’r (July 9, 2021), https://www.sfexaminer.com/archives/data-shows-chesa-boudin-prosecutes-fewer-shoplifters-than-predecessor/article_7dbc7d85-cde9-59d9-8f23-7b240ee6f26d.html (under Boudin, the number of charges for petty theft drastically decreased in 2021). ↑

- . Rachel Scheier, San Fransisco Confronts a Crime Wave Unusual Among U.S. Cities, L.A. Times (Jan. 3, 2022), https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-01-03/san-francisco-property-crime-spikes; Rachel E. Morgan & Alexandra Thompson, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Bureau of Just. Stat., Criminal Victimization, 2020 (2021), https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/cv20.pdf. ↑

- . Scheier, supra note 82. ↑

- . Thomas Hogan, Guaranteed Murder, City J. (Nov. 26, 2021), https://www.city-journal.org/article/guaranteed-murder. ↑

- . Bryan Polcyn, Darrell Brooks Freed on Bond Before Parade, No Record of Hearing, Fox 6 Milwaukee (Nov. 30, 2021), https://www.fox6now.com/news/darrell-brooks-freed-on-bond-before-parade-no-record-of-hearing. ↑

- . See Jeffrey Toobin, The Milwaukee Experiment, New Yorker (May 4, 2015), https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/05/11/the-milwaukee-experiment (opponent criticizing Chisholm’s approach of releasing incarcerated people back into society, where minority communities are inevitably victimized). ↑

- . Chase Sackett, Neighborhoods and Violent Crime, Evidence Matters (2016), https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/em/summer16/highlight2.html. ↑

- . Neighborhood Poverty, Nat’l Equity Atlas, https://nationalequityatlas.org/indicators/Neighborhood_poverty (last visited Nov. 1, 2024); see also John Creamer, Inequalities Persist Despite Decline in Poverty For All Major Race and Hispanic Origin Groups, U.S. Census Bureau (Sept. 15, 2020), https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2020/09/poverty-rates-for-blacks-and-hispanics-reached-historic-lows-in-2019.html. ↑

- . Erika Harrell et al., U.S. Dep’t of just., Bureau of Just. Stat., Household Poverty and Nonfatal Violent Victimization, 2008-2012 1 (2014), https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/hpnvv0812.pdf; see also Melissa S. Kearney & Benjamin H. Harris, The Unequal Burden of Crime and Incarceration on America’s Poor, Hamilton Project, (Apr. 28, 2014), https://www.hamiltonproject.org/publication/post/the-unequal-burden-of-crime-and-incarceration-on-americas-poor/. ↑

- . Rachel Morgan & Alexandra Thompson, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Criminal Victimization, 2020—Supplemental Statistical Tables (2022), https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/criminal-victimization-2020-supplemental-statistical-tables. ↑

- . Conor Friedersdorf, Criminal Justice Reformers Chose the Wrong Slogan, The Atlantic (Aug. 8, 2021), https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/08/instead-of-defund-the-police-solve-all-murders/619672/. ↑

- . Robert VanBruggen, An Update on America’s Homicide Search, City J. (Jan. 25, 2023), https://www.city-journal.org/update-on-americas-homicide-surge. ↑

- . These Are Nine Stories from America’s Homicide Crisis, Wash. Post (Nov. 27, 2022), https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/interactive/2022/america-homicide-victim-stories/; James Freeman, Bloody Blue Cities, Wall St. J. (Nov 28, 2022), https://www.wsj.com/articles/bloody-blue-cities-11669674866. ↑

- . Keechant Sewell, New York City Police Dep’t., Crime and Enforcement Activity in New York City 11 (2021), https://www.nyc.gov/assets/nypd/downloads/pdf/analysis_and_planning/year-end-2021-enforcement-report.pdf. ↑

- . TaRhonda Thomas, Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner Looks to Clear Air After ‘No Crisis of Crime’ Comment, 6ABC (Dec. 9, 2021), https://6abc.com/philly-da-larry-krasner-crisis-of-crime-philadelphia-district-attorney-gun-violence/11317164/. ↑

- . Cleve R. Wootson, The White DA, the Black ex-Mayor and a Harsh Debate on Crime, Wash. Post (Dec. 28, 2021), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/12/28/krasner-nutter-philadelphia-crime/. ↑

- . See supra Part I. ↑

- . Hogan, supra note 84. ↑

- . Palumbo, supra note 59. ↑

- . Safe Neighborhoods and Schools Act, supra note 3. ↑

- . John Ketcham, Correcting Course, City J. (Apr. 11, 2022), https://www.city-journal.org/ny-state-budget-negotiations-yield-criminal-justice-changes. ↑

- . Palumbo, supra note 59. ↑

- . Christensen, supra note 8. ↑

- . Kevin Held et al., St Louis Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner Resigns, Effective June 1, Fox2 (May 4, 2023), https://fox2now.com/news/missouri/st-louis-circuit-attorney-kim-gardner-resigns-effective-june-1/. ↑

- . Ashley Sharp, Theft and Drug Crackdown? Proposed Measure to Reform Prop 47 Gathers Last Signatures for November Ballot, CBS News (Mar. 6, 2024), https://www.cbsnews.com/sacramento/news/measure-to-reform-prop-47-gathers-last-signatures-november-ballot/. ↑

- . Opinion, Oregon Rethinks Drug Decriminalization, Wall St. J. (Jan. 29, 2024), https://www.wsj.com/articles/oregon-rethinks-drug-decriminalization-measure-110-aclu-744d2544. ↑

- . Opinion, Refunding the San Francisco Police: Mayor London Breed Undergoes a Law-and-Order Conversion, Wall St. J. (Dec. 16, 2021), https://www.wsj.com/articles/refunding-the-san-francisco-police-london-breed-crime-11639696468. ↑

- . Aaron Blake, Biden Tries to Nix ‘Defund the Police,’ Once and for All, Wash. Post (Mar. 2, 2022), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/03/02/biden-nix-defund-police/. ↑