By Ali Fenno

On November 8, 2016, the Fourth Circuit issued a published opinion in the civil case of Thomas v. Salvation Army. In Thomas, the Fourth Circuit addressed whether the Western District of North Carolina properly dismissed Sharon Thomas’s (“Thomas”) various claims against three charitable organizations that allegedly refused to admit her to homeless shelters because of her mental disability. The Fourth Circuit held that Thomas did not allege sufficient facts to support her claims and affirmed the lower court’s dismissal of the case.

Facts and Procedural History

On July 22, 2012, Thomas was admitted to defendant Salvation Army’s homeless shelter after being referred there by an organization that provided her with behavioral mental health services. Shortly thereafter, Salvation Army transferred Thomas to defendant Church in the City, a stricter shelter run by the final defendant, Victory Christian Center, because Salvation Army’s shelter had become too crowded.

Thomas disclosed her mental health issues immediately upon arriving at Church in the City. While living there, she returned to Salvation Army for two separate visits, at which she disclosed that she was receiving behavioral mental health services, authorized the release of some of her medical records to Salvation Army, and was referred to a behavioral health center.

On August 12, 2012, Church in the City evicted Thomas. Thomas was given no reason for her eviction and alleged that she had never missed curfew. She tried to be readmitted to the Salvation Army shelter but was turned down because she was evicted from Church in the City. Thomas made numerous other attempts to return over the next few days, but was still denied re-entrance on the grounds that she had violated Church in the City’s curfew and was not a good fit for the shelter. One staff member told her that she would likely be admitted after getting a mental health evaluation, but the shelter later refused Thomas admission when she returned with psychiatric discharge papers.

Thomas did not attempt to return to the shelter after this last attempt, but she continued to try to discover why she was denied admission. In September, a Salvation Army caseworker that had investigated her case informed her that her dismissal had been justified because she had been disrespectful and hostile towards the shelter staff. He offered her admission to the shelter if she submitted a mental health evaluation and received behavioral mental health services. Thomas instead requested records of her stay at the shelter and of the relationship between Salvation Army and Church in the City. This request was denied.

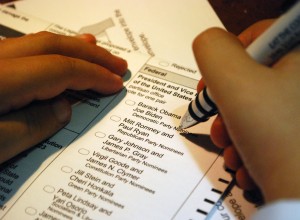

Nearly two years later, Thomas filed this action in the Western District of North Carolina, moving to proceed in forma pauperis. Although the district court granted the motion, in the very same order it dismissed all of her claims under 28 U.S.C. § 1915(e)(2)(B)(ii) for failure to state a claim on which relief could be granted. The court also warned Thomas that it would require her to show cause as to why it should not enter a pre-filing injunction against her if she continued to file meritless lawsuits.

Thomas then appealed to the Fourth Circuit, challenging her appeals under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 (“§ 1983”), 42 U.S.C. § 1985 (“§ 1985”), the Americans with Disabilities Act (“ADA”), the Fair Housing Act (“FHA”), and the Rehabilitation Act.

§ 1915(e)(2)(B)(ii) Standard of Review

The Fourth Circuit established that the standard for reviewing a dismissal under § 1915(e)(2)(B)(ii) is the same as that for a dismissal under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6). It therefore reviewed the district court’s dismissal de novo and accepted Thomas’s pleaded facts as true. Because Thomas was a pro se plaintiff, the court liberally construed the allegations in her complaint, but it maintained that her claims for relief must still be plausible on their face.

Lack of State Action Invalidates § 1983 Claim

The Fourth Circuit first determined that Thomas’s § 1983 claim was correctly dismissed because the defendants were not state actors. It recognized that § 1983’s color of law requirement does not cover private conduct, and private conduct can only be converted to state action when the state dominates the private activity. Here, because all three defendants were private organizations and Thomas did not allege any facts attributing their actions to the state, the Fourth Circuit held that Thomas had not plead a valid § 1983 claim.

Lack of a Conspiracy Invalidates § 1985 Claim

The court next approved the dismissal of Thomas’s § 1985 claim, holding that she did not allege any facts supporting the existence of a conspiracy between Salvation Army and Church in the City. Although Thomas alleged that her Salvation Army badge included a mention of Church in the City and that her inability to return to Salvation Army was due to her ejection from Church in the City, the court concluded that these facts only showed that the charities worked together to help Charlotte’s homeless population. Thomas’s remaining allegation that Salvation Army conspired with Church in the City was merely conclusory, which is not enough to proceed on a § 1985 claim.

No Standing for an ADA Claim

The Fourth Circuit then addressed Thomas’s ADA claim. The district court dismissed the claim on the grounds that Title I of the ADA requires a plaintiff to exhaust her administrative remedies before pursuing civil litigation. But the Fourth Circuit rejected this reasoning, noting that Title I of the ADA only applies to claims concerning employment, and here, Thomas’s claim did not concern employment.

However, the Fourth Circuit still found that that Thomas lacked standing to bring an ADA claim pursuant to both Title II and Title III of the ADA. Title II did not apply because it only applies to actions against public entities, and in this case, none of the defendants were public entities. Title III, though applying to places of public accommodation like the shelters in Thomas, still did not give the plaintiff standing because it only provides a private right of action for injunctive relief. The court noted that injunctive relief is only available to plaintiffs that show they have suffered irreparable injury, which requires a showing of a real or immediate threat that the plaintiff will be harmed again. Here, the court concluded that Thomas did not show a real or immediate threat that she would be harmed again because all the alleged harms occurred over two years before the action was filed. Furthermore, Thomas admitted that she filed the relief not to prevent future discrimination, but because of her “persistent and distressing memories” of the past discrimination. Accordingly, the court concluded that the ADA claim was invalid because the facts alleged in Thomas’s complaint did not establish irreparable harm entitling her to injunctive relief.

Lack of Discrimination Invalidates FHA Claim

The Fourth Circuit approved the dismissal of Thomas’s FHA claim because her complaint did not contain a plausible allegation of discrimination. The court first noted that the FHA prohibits “mak[ing] unavailable or deny[ing] . . . a dwelling to any buyer or renter because of a handicap,” and that a handicap is “a physical or mental impairment which substantially limits one or more of such person’s major life activities.” Here, Thomas did not adequately identify a mental impairment for the purpose of the FHA: she identified her mental illness as a mood disorder, but then alleged that she was “mentally stable” and that the mental evaluation requested by Salvation Army was not necessary.

Even if Thomas had identified a valid mental illness, the court concluded that she did not allege facts establishing a nexus of causation between that illness and the defendants’ actions. The complaint listed multiple reasons besides Thomas’s mental disability for her eviction from the shelters, and the court further found that Thomas’s behavior with staff members gave Salvation Army valid grounds for requesting mental health examinations and records. Accordingly, the Fourth Circuit held that Thomas’s FHA claim must be dismissed because her factual allegations did not amount to a plausible showing of a mental impairment and causation, which are both essential to proving the discrimination element of a FHA claim.

Failure to Meet the Rehabilitation Act’s Heightened Causation Standard

The Fourth Circuit last concluded that Thomas failed to meet the Rehabilitation Act’s heightened causation standard. Like the ADA and FHA, the Rehabilitation Act forbids discrimination based on a disability. However, the court noted that it is different in two ways: (1) it applies only to programs receiving federal assistance, and (2) the plaintiff must show that the discrimination was solely by reason of her disability. The court first recognized that the Plaintiff only alleged that the Salvation Army received federal funding; there was no mention in the complaint of such funding for Church in the City or Victory Christian Center. It then reasoned that the second causation element must fail for the same reasons the FHA claim failed: (1) the complaint failed to allege a mental illness qualifying as a disability under the Act, and (2) it did not establish a nexus of causation between Salvation Army’s refusal to admit her and that disability. Accordingly, the court affirmed the district court’s dismissal of the claim.

Conclusion

Because the Fourth Circuit approved the dismissal of all five of Thomas’s claims, it also affirmed the district court’s decision to not exercise supplement jurisdiction over Thomas’s state law claims and to dismiss them without prejudice. However, the court noted that Thomas was not given an opportunity to respond before the district court dismissed her complaint sua sponte or to amend her complaint. Thus, the Fourth Circuit affirmed the decision of district court but modified it so that the dismissal would be without prejudice.