By: Lesley Wexler

This article is only available in PDF format. Click here for the full PDF version of this article.

By: Lesley Wexler

This article is only available in PDF format. Click here for the full PDF version of this article.

By: Michael Selmi*

The Civil Rights Act of 1991 (“CRA”) sought to change the employment discrimination landscape. The CRA overturned or repudiated eight Supreme Court decisions that had narrowed the scope of Title VII in a way that Congress determined was inconsistent with the broad purpose of eradicating employment discrimination.[1] Relatedly, the CRA transformed Title VII from an equitable relief statute—under which attorneys were most commonly compensated through attorney fee petitions—to a tort-like statute that allows for jury trials and damages for claims relating to intentional discrimination. The CRA also marked the most comprehensive amendment to the original Civil Rights Act; although Title VII had been amended several times previously, the CRA was, by far, the most substantial amendment then or now.[2]

In this Article, I will explore the effect the CRA has had on employment discrimination litigation, primarily in the Supreme Court, but I will also glance toward litigation in the lower courts. Based on a review of the Title VII cases and other related cases the Court has decided over the last twenty years,[3] it appears that the CRA had a meaningful restraining effect on the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence. Since the CRA was passed, the Court has generally, though by no means always, been more supportive of plaintiffs’ Title VII claims than it had been in the years immediately preceding the CRA. There is, however, an important caveat: in the most ideological cases, or those cases that might have the most dramatic effect on litigation, the Court has remained decidedly pro-defendant. In other words, in the most meaningful cases, plaintiffs continue to encounter a hostile Supreme Court. It also appears that the changes wrought by the CRA did not substantially improve outcomes for plaintiffs, though there was, especially in the early years, a dramatic increase in filings. On the whole, plaintiffs have fared only marginally better on the merits, and employment discrimination cases continue to be more difficult to win than most other comparable civil cases.

This Article will proceed in two primary parts. The first Part will explore the cases that preceded the CRA and introduce the positive political theory framework through which I want to analyze the Court’s response. Positive political theory sees the relationship between the judicial, legislative, and executive branches as a political game designed to assert preferences; several scholars have assessed the origins of the CRA against the positive political theory framework.[4] The second Part of the Article will go beyond those analyses to assess the Supreme Court’s response to see how the Court has adopted a strategically sophisticated approach that has diverged significantly from its interpretative path prior to the CRA.

The history behind the CRA is well known and I will provide only a cursory outline, some of which is informed by my experiences as a staff attorney with the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights at the time the Act was under consideration. Although I played a rather minor monitoring role, the Lawyers’ Committee and my direct supervisor, Rick Seymour, were heavily involved in the drafting and negotiating of the legislation, and I later became enmeshed in some of the early litigation interpreting the CRA.

During the 1980s, the Supreme Court took a deeply conservative turn on issues of civil rights, particularly with respect to employment discrimination. The Court repeatedly reached adverse results for plaintiffs, and even in cases in which the plaintiffs prevailed, the Court would often impose significant limitations on the employment discrimination doctrine.[5] There were a substantial number of cases that limited the rights of plaintiffs, but three cases decided during the 1989 term were particularly important in prompting congressional action.

Probably the most significant departure from prior precedent came in the case of Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, in which the Court severely restricted the scope of § 1981.[6] The statute had never been a major source of employment rights, but it was one of the original civil rights statutes enacted during Reconstruction, and it had a long history that the Supreme Court effectively ignored in holding that the statute only applied to contract formation, and not to acts of discrimination that occurred thereafter.[7] Not only did the Court limit the statute’s reach, it did so aggressively and on its own initiative. After the case was initially briefed and argued on the question of the statute’s scope, the Court, on its own motion, called for reargument on whether the statute should apply to private parties, an issue the Supreme Court had addressed in Runyon v. McCrary[8] just a decade earlier and that the parties had not raised.[9] Ultimately, the Court backed away from that radical reinterpretation, in part because of an outpouring of briefs and critical public reaction,[10] but the Court’s gesture, and its limitation of the statutory scope, sent a signal that settled civil rights principles were up for reconsideration.

During the same term, the Court also rewrote the law with respect to class action settlements. In Martin v. Wilks, a group of white firefighters sought to intervene in a case that had been resolved through a consent decree many years earlier.[11] The white firefighters sought to challenge the remedial provisions in the decree, which they argued impermissibly limited their opportunities within the fire department; by a five-to-four vote, the Court permitted the intervention, even though the firefighters had the opportunity to contest the decree when it was originally entered.[12] This meant that, despite the Court’s frequent admonitions regarding the importance of finality in litigation, it would often be difficult to determine when a settlement embodied in a consent decree could be assumed to be final and free from challenge. It also meant that a new group of firefighters could challenge settlements that their predecessors had accepted.[13]

The Wilks case also offers important context for understanding the Court’s direction during this time period. The consent decree at issue in Wilks provided for preferential treatment of African American firefighters as part of the remedies that had been incorporated into the decree.[14] The case therefore became part of the affirmative action debate that was raging throughout much of the 1980s, and was seen as integral to the Reagan administration’s broader assault on civil rights and affirmative action.[15] Even though the administration had been unsuccessful in many of the cases,[16] the Wilks case was seen as giving a green light to efforts to dismantle remedial orders.[17] From this perspective, the Court’s decision was fully consistent with the position espoused by the Reagan administration—and to a lesser extent by the Bush administration—and the Democratic Congress became concerned with what the future might hold.[18]

While Wilks and Patterson reflected the Court’s hostility toward employment discrimination claims, the coup de grâce came with the Court’s decision in Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio, a complicated case in which the Court rewrote part of the disparate impact law to place the burden of proof of the business-necessity defense squarely on the plaintiffs.[19] Although the Court’s decision was seen as a significant change in the law, it had also become clear that a majority was developing on the Court in favor of eliminating the disparate impact theory altogether—a theory the Court had created in common law fashion in its landmark Griggs decision.[20] Like Wilks, Wards Cove was also seen as indirectly connected with the affirmative action debate, given that the disparate impact theory had often, and mistakenly, been seen as prompting employers to adopt quotas as a way of avoiding litigation.[21] The Wards Cove case was decided on the last day of the same term that produced the Wilks and Patterson decisions; shortly after the term ended, Congress began work on what was then dubbed the Civil Rights Act of 1990.[22]

While the three cases discussed above played the strongest role in motivating Congress to act, the Court issued a number of other controversial decisions on smaller issues, all of which made it more difficult for discrimination plaintiffs to obtain relief on their claims. Some of the issues involved interest on judgments and awards of expert fees,[23] while others involved the timing of claims[24] or the extraterritorial application of Title VII.[25] Together these cases represented a clear hostility to the interests of plaintiffs—a hostility that became particularly apparent when seen in connection with a series of nonemployment discrimination cases decided at the same time that reflected a broader hostility to civil rights claims, particularly in the area of affirmative action.[26] When we turn to an assessment of the effects of the CRA, it is important to keep these smaller cases in mind, as in the 1980s no case seemed too small for the Court to side with employers.

Once the legislation began to move through Congress, several obstacles became apparent. With President George H.W. Bush in office, the Democratically controlled Senate had to secure the votes necessary to overcome a presidential veto. Many of the proposed provisions were uncontroversial, and there was also widespread agreement that Title VII plaintiffs should be afforded jury trials with damages available.[27] At the same time, a group of Republican Senators were intent on making the bill part of a larger tort-reform effort and therefore sought to place caps on the damages provisions.[28] Among some in Congress, there was a sense that capping the damages in Title VII cases would lead to damage caps in other federal statutes, although efforts to impose broader tort reform stalled shortly after the passage of the CRA.[29]

The most controversial part of the legislation was the provision designed to overturn the Wards Cove decision. As I have argued elsewhere, the disparate impact theory has always rested uneasily within antidiscrimination law and it has likewise always been equated with affirmative action, an issue that was particularly divisive at the time.[30] The Supreme Court, and politicians, had cautioned against aggressive interpretations of the disparate impact law for fear that employers would be forced to adopt quotas as a way to avoid lawsuits.[31] This always seemed mostly a specious argument given that the disparate impact theory had been in existence since 1971, with reasonably aggressive interpretations in the 1970s, without any hint of broadscale quota-motivated hiring.[32] In any event, the rhetoric proved powerful and the disparate impact provisions became hotly contested and produced a series of innovative legislative provisions.

Within the Senate, a debate broke out regarding whether Wards Cove was truly a departure from past precedent, eventually leading to dueling legislative memoranda that were written primarily by interest groups.[33] At least in this particular instance, Justice Scalia’s theory of statutory interpretation was given full credence, as the memoranda were naked attempts to influence how the statute should be interpreted almost entirely independent of the legislators themselves, though not independent of their staffs, which had been deeply involved in the process.[34] As a result, the Senate inserted a most peculiar provision into the statute forbidding courts from looking to the legislative history.[35] The Wards Cove company also got its hands in the legislative cookie jar, as it was worried that the legislative fix might undo its ten-year victory, and the company eventually purchased its own statutory provision that exempted the Wards Cove case from the legislation.[36]

Despite all of the legislative maneuvering, the controversy refused to die, and President Bush vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1990 due to the disparate impact provision.[37] Congress failed in its override attempt but immediately set out to craft a new bill, although the prospects for passage remained dim until the Clarence Thomas hearings intervened.[38] While Congress was debating what was then known as the Civil Rights Act of 1991, Anita Hill’s allegations of sexual harassment surfaced, which led to a public debate over the emerging sexual harassment doctrine. Those hearings ultimately contributed to the passage of the CRA; indeed, I think it is fair to say that without the hearings, there may not have been a CRA.[39] There were two reasons for this connection. First, Missouri Senator John Danforth was both a Republican sponsor of the CRA and the shepherd for Clarence Thomas, who had worked for the Senator many years earlier in the Missouri Attorney General’s office.[40] After the Anita Hill allegations arose, Senator Danforth pledged to ensure Thomas’s nomination and the passage of the CRA—a pledge he ultimately lived up to.[41]

Second, and sometimes lost in the story, was the realization during the hearings that victims of sexual harassment were often left without any meaningful remedy. Not only did civil rights advocates have Justice Thomas to thank for the passage of the CRA, Judge Daniel Manion from the Seventh Circuit also chipped in with his own contribution.[42] In a case involving clear and uncontested sexual harassment, Diane Swanson had been denied any relief since she did not lose her job and therefore did not suffer monetary loss.[43] Not content to simply deny her relief, the Seventh Circuit went on to conclude that because she was not eligible for any relief, she had no claim and therefore was responsible for the defendant’s court costs, which were taken directly out of her paycheck.[44]

As noted at the outset, the CRA overturned parts or all of eight Supreme Court decisions, and it added important new remedial provisions to the statute.[45] Equally important, the CRA sent a strong signal that Congress believed the Court was interpreting Title VII too narrowly, and there was language to this effect included in the statutory preface.[46] The debate over the Act occurred in a very public forum over the course of two years and tainted the arrival of the Court’s newest member. All of this is to suggest that it would have been difficult for the Supreme Court to ignore the message behind the CRA, but it was less clear whether the Act would have its intended effect. Some of the provisions were effectively self-executing: the interest and attorney’s fees provisions allowed for little judicial interpretation, and the provision designed to overturn Martin v. Wilks also turned out to be a clear directive that produced no meaningful subsequent litigation. But the real question was whether the Supreme Court would take Congress’s broader message seriously and interpret Title VII with an eye toward fulfilling the underlying purpose of the CRA rather than with an eye toward protecting employers.

The message sent by—as opposed to the substantive provisions of—the 1991 Act raises important questions about the relationship between Congress and the Court. Here Congress was not only reversing specific decisions but was also seeking to change the Court’s interpretive direction. Congress’s oversight powers, however, are limited; Congress could always pass new legislation to change or modify Supreme Court decisions, but short of new legislation the Court is largely free to ignore congressional directives. Suggesting that the Court is free to ignore congressional directives assumes that the Court may have its own interests or preferences in mind in interpreting statutes. Most scholars who concentrate on statutory interpretation assume that a court’s judicial duty is to interpret the statute consistent with congressional intent, with the primary area of contention being what Congress intended.[47] Positive political theorists, on the other hand, treat courts as political actors who desire to implement their own preferences; these theorists typically see modes of statutory interpretation as rhetorical, rather than restraining.[48] Numerous empirical scholars have also documented that courts frequently decide cases based on judges’ presumed ideological preferences.[49] For a conservative court, when it comes to issues of employment discrimination, those preferences are most likely to include insulating employers from liability, and as we have just seen, that was how the pre-CRA Court proceeded.

Yet the Court was ultimately unsuccessful, and within the positive political theory framework, a court that wants to implement its preferences must avoid having its decisions overturned. As a strategic matter, this can lead to some complex analysis, as the Supreme Court would be primarily concerned not with the Congress that enacted a statute but with the current Congress that would be responsible for passing any new legislation, and, similarly, with the President who might veto the legislation.[50] Under this guise, the Court clearly played the game poorly in its discrimination decisions of the late 1980s, since those decisions all had a very short shelf life. In light of the CRA’s repudiation of those decisions, we might expect the Supreme Court to change its game plan. As we will see, that is precisely what it did—and it did so in a strategic way that has protected most of the decisions the Court seems to care most about.

This Part will assess the Supreme Court’s behavior following the passage of the CRA in 1991 and will demonstrate that the Court has acted as positive political theory would predict. Apparently chastened by the CRA rebuke, the Court has proceeded more wisely, ruling for plaintiffs in the majority of cases, often unanimously, while siding with the interests of employers in the cases that matter most. During this time period, from 1993 to 2009, the Court’s composition has changed but it has remained a fundamentally conservative Court, one that arguably is more conservative than the Court that issued the decisions that led to the CRA.[51] It is important, however, to highlight the Court’s process—many of the cases the Court has adjudicated over the last two decades have raised rather minor issues, and a surprising number of cases were simply necessary to reverse plainly incorrect lower court cases. In these minor cases, the plaintiffs have uniformly prevailed. But there were also a handful of controversial and important cases, and in those cases the defendants have prevailed, suggesting that the Court was still willing to implement its preferences, at the risk of reversal, in the cases of greatest significance. Finally, there were cases addressing issues of intermediate importance in which the plaintiffs fared well, and it is in this handful of cases that the Court likely exercised the most judicial restraint.

Before discussing the cases, I must address several preliminary matters. As noted previously, I have excluded disability cases from the analysis, primarily because the CRA was not aimed at the disability statute. The Court unquestionably interpreted the ADA narrowly, and Congress recently passed legislation intended to modify the Court’s approach in several of the cases;[52] it will be interesting to see how the Court responds, and if the CRA offers any guidance to the Court’s likely reaction to the statutory repudiation. I have also excluded most of the cases that involve arbitration agreements since the cases have primarily involved interpretation of a different statute—the Federal Arbitration Act[53]—or issues not directly related to discrimination claims.[54] I have, however, included the several cases that directly involve discrimination issues. Finally, I should note that classifying several of the cases has required subjective determinations as to who prevailed in a case, and also as to whom the doctrine is most likely to benefit. I will highlight where I have made such judgments.

Immediately following the passage of the CRA, the Supreme Court appeared to be up to its old tricks. The first two cases the Supreme Court addressed involved the retroactivity of the statute—specifically, whether the CRA applied to cases that were pending at the time of enactment.[55] In both cases, the Court held that the CRA did not apply retroactively but instead only applied to controversies that arose after it was passed.[56] This effectively delayed implementation for several years. Notably, however, both decisions were written by Justice Stevens with Justice Blackmun as the lone dissenter, and there was substantial support for the Court’s decision both in the legislative history, which was purposefully left unresolved, and in the body of law that had developed regarding the retroactive application of legislation.[57] The Court also decided the controversial St. Mary’s Honor Center v. Hicks case after the CRA was passed, but the case itself had little to do with the statute even though the Court’s decision made it more difficult for plaintiffs to prevail in certain cases.[58] Yet if we view Hicks as part of the post-CRA history, the Court’s treatment is consistent with the pattern we observe in other cases—namely, that the most significant cases remain solidly in the defendants’ camp.

After Hicks, the Court heard a series of cases in which plaintiffs prevailed, often through unanimous decisions. In Appendix A, I provide a list of the cases decided since the CRA was passed, noting the party that prevailed, the year the case was decided, and the Supreme Court vote breakdown. The results are revealing: the Supreme Court decided forty-three cases in connection with Title VII, the ADEA, and § 1981, and in twenty-nine, or 67.4%, of those decisions found in favor of the plaintiffs. The defendants prevailed in thirteen, or 30.2%, of the cases.[59] Of the forty-three decisions, twenty were unanimous, 46.5% of the total, and, remarkably, eighteen of the unanimous decisions were in favor of plaintiffs. Indeed, nearly two thirds (62.1%) of the decisions favoring plaintiffs were unanimous.[60]

Table 1: Employment Discrimination Cases Decided 1993–2010

| Decision | Plaintiff | Defendant |

| Prevail | 29 | 13 |

| Unanimous | 18 | 2 |

| 5–4 | 1 | 5 |

The high number of unanimous decisions in favor of plaintiffs offers a sharp contrast to the Court’s decisions rendered prior to the CRA. During the period 1986–1989, there were five unanimous decisions and all but one had a significant concurring opinion supporting a more limited approach.[61] Interestingly, none of the unanimous decisions were issued during 1989, when the Court was most active in limiting the scope of Title VII.[62] In terms of substance, only one of the unanimous cases involved race discrimination, while three involved important issues relating to sex discrimination. In contrast, the cases that most clearly prompted the CRA—Patterson, Wilks, and, to an extent, Wards Cove—all involved issues of race discrimination, as was true for most of the controversial affirmative action cases that arose during this time period.[63]

Table 2: Employment Discrimination Cases Decided 1987–1991

| Decision | Plaintiff | Defendant |

| Prevail | 10 | 12 |

| Unanimous | 5 | 0 |

| 5–4 | 1 | 3 |

| 6–3 | 2 | 4 |

The substantial rise in unanimous decisions not only represents a change in course for the Supreme Court but also highlights an important issue embedded in these cases—namely, just how conservative some of the lower courts have become. Perhaps more accurately, the cases indicate how much more conservative some of the lower courts are compared to what is generally viewed as a very conservative Supreme Court. While it is difficult to draw any conclusions based on this small sample, it is worth noting that of the eighteen unanimous decisions, eleven originated from the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Circuits, with the Sixth leading the way with five unanimous reversals. Only one of the unanimous decisions was an outright affirmance, and that was the mixed-motives case Desert Palace, Inc. v. Costa,[64] which arose out of the Ninth Circuit, often considered the most liberal appellate court. Some of the cases involved appellate decisions that were clearly outliers and were essentially summarily reversed. For example, the Fourth Circuit held that to establish a prima facie age discrimination claim, an individual had to demonstrate that she had been replaced by someone outside of the protected class, a holding that had no support in the statutory language and that the Supreme Court reversed in a seven-paragraph opinion.[65] The same court also held that former employees could not bring Title VII claims, excising from the statute anyone who was no longer employed.[66] This latter case had some resemblance to the Supreme Court’s decision in Patterson—as both cases involved the scope of the statute—and suggests that the Supreme Court may have taken seriously Congress’s directive to interpret the statutes consistently with their underlying purposes.

Perhaps the most interesting of the unanimous decisions reversing a hostile lower court was a case that involved racial epithets. In Ash v. Tyson Foods, Inc., the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals had held that the use of “boy,” when directed at an African American man, was not evidence of discriminatory intent unless it was qualified by a racial term such as “black.”[67] In a per curiam rebuke, the Supreme Court rejected the need for the racial qualifier, noting that whether the term was evidence of discrimination should be considered within its context and in conjunction with additional evidence the plaintiff produced.[68] In the same case, the Court also rejected the appellate court’s standard—that pretext could only be established by comparison to the employer’s treatment of others to the extent the “disparity in qualifications is so apparent as virtually to jump off the page and slap you in the face.”[69] Despite the Supreme Court’s sound rejection, the Eleventh Circuit recently reaffirmed a dismissal of the case, albeit under slightly different legal standards.[70]

Another noteworthy aspect of the unanimous cases is that most of the cases were of minor significance. Several had to do with procedural issues that had not been resolved in the thirty-year history of Title VII, such as the requirements for verifying a complaint and the method for counting employees to meet the statutory coverage requirement.[71] The Supreme Court decided only two cases during the Wards Cove era that presented similar interpretive questions,[72] and in these and other cases, the Court has recently taken a pragmatic rather than literal linguistic approach. This was true in the Court’s definition of “employee” and its determination that the number of employees is not a jurisdictional issue, even though there were substantial arguments in support of the other side on both issues.[73] In the earlier era, it seems quite likely that the Court would have ruled differently, or, more likely, allowed the lower court decisions to stand without review.[74]

Not all of the unanimous cases have turned on minor issues. The Court held that Title VII prohibits same-sex harassment,[75] an issue that had caused considerable havoc in the lower courts; tossed aside any remnant of the pretext-plus issue;[76] and in two cases, crafted quite liberal principles of law relating to retaliation claims.[77] Indeed, if there has been any major and surprising turn of events, it has been the Supreme Court’s protective approach to retaliation claims. Plaintiffs have prevailed in all five retaliation claims the Court has considered, and the Court has adopted an expansive interpretation of the statute in each case. In one of the cases, the Court had to identify a retaliation claim when the statute was arguably silent or at best ambiguous on the issue.[78] These cases have helped spark a sharp rise in retaliation claims, but despite that increase, the Court has not sought to cut back on its broad interpretations, and it is difficult to see the Court as anything other than genuinely protective of retaliation claims.[79]

The plaintiff-friendly cases demonstrate that the Supreme Court has moved in a direction that has been more protective of victims of discrimination, but there is an important countertrend that offers a clear balance and also suggests that the Court may be playing a sophisticated political game. In the most significant cases—including the sole employment case to touch on questions relating to affirmative action[80]—the defendants continue to prevail, and often by five-to-four majorities. In these cases, the Court continues to impose its preferences, but now does so while also issuing a series of pro-plaintiff decisions, most of which likely do not implicate clear preferences of the Court. There have been five decisions in favor of defendants by a five-to-four margin, and at least four of the cases are among the most significant decided since the CRA.[81] As noted previously, the Supreme Court began the post-CRA era with a five-to-four decision in St. Mary’s Honor Center v. Hicks, in which it held that proof of pretext leads to a permissive inference of discrimination rather than the mandatory presumption advocated by the plaintiffs and adopted by the lower court.[82] That decision also kept alive the damaging pretext-plus theory, though only by disingenuous lower court interpretations, which the Supreme Court abrogated nearly a decade later.[83]

More recently, the Supreme Court has issued several controversial decisions favoring defendants. In Ricci v. DeStefano, the conservative majority of the Court invalidated an employer’s voluntary efforts to remedy the adverse impact of several promotion tests it had administered.[84] Reverting to its Wards Cove days, the Court deemed the tests valid even though the tests had not been subject to any legal scrutiny and despite strong arguments that the tests could not be validated under existing law.[85] The Ricci case has drawn considerable attention and harkens back to the assault on affirmative action from the 1980s, as the Court appeared to view the city’s remedial action as akin to instituting racial preferences for the minority firefighters.[86] The following term, the Court also held that the mixed-motives theory, often seen as a boon to plaintiffs, was not available under the ADEA, even though the language at issue in the ADEA was quite similar to the language in Title VII that permits such claims.[87] The difference in results between cases decided under Title VII and the ADEA may be a sign that statutory language can, in fact, restrain the Court. Although the Court announced a liberal standard for Title VII claims based on language from the CRA, that language did not apply to the ADEA, leaving the Court free to implement its preference on age claims.

Table 3: Five-to-Four Decisions: 1993–2010

|

The other noteworthy five-to-four decision reveals that the Court can still overplay its hand. In the only employment discrimination case to receive more attention than Ricci, the Supreme Court held that Lilly Ledbetter had waited too long to file her wage discrimination claim.[88] There were, to be sure, some pragmatic aspects to the case that led the Court to side with the employer. However, in doing so, the Court imposed a restrictive standard that would have likely foreclosed most wage discrimination claims since it can often take employees years to learn that pay raises were issued in a discriminatory fashion. In her dissenting opinion, Justice Ginsburg called on Congress to act,[89] and it quickly did so. Just over a year after the decision was issued, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act (“Fair Pay Act”) became the first bill President Barack Obama signed into law, thus reversing the Supreme Court’s decision and likely expanding the statute of limitations beyond what had existed in most of the lower courts.[90] The case, and the subsequent Fair Pay Act, also drew attention to the issue of pay equity in a way the Court likely did not intend, and there is little question that to the extent the Court was seeking to insulate employers from wage discrimination claims, its Ledbetter decision ultimately had the opposite effect.[91] Nevertheless, the unintended consequences may prove more theoretical than real, as to date there has not been any significant increase in wage claims, and a bill to address pay equity issues has failed to gain traction.[92]

I should also note that rather than overplaying its hand, the Supreme Court may have misjudged future election results. The Ledbetter decision was issued toward the end of the Bush presidency but before the Democrats took over the presidency and both houses of Congress. It is certainly possible that had the decision been issued the following year, the Court may have sought a more moderate path, although its decision in the Ricci case may suggest otherwise. There is, however, an important distinction between those two cases: Ledbetter was purely a matter of statutory interpretation and relatively easy to overturn, while Ricci represented an amalgam of interpretations of past Supreme Court precedent with overlays of constitutional considerations. The Ricci case also involved race, whereas Ledbetter presented a more appealing sex discrimination claim that was ripe for congressional review.

In addition to the unanimous decisions for plaintiffs and the five-to-four decisions for defendants, there was a series of cases decided by various margins and also a set of cases in which it was difficult to determine what party would ultimately come out ahead. These latter cases included three in which the Court provided a legal standard that was generally protective of plaintiff interests, and then carved out an affirmative defense to encourage employers to take precautionary measures.[93] The Court first took this step in a pair of sexual harassment cases in which it crafted an affirmative defense out of thin air—but a defense that also seemed consistent with the purpose behind the CRA, which is to prevent rather than remedy harassment.[94] What is perhaps most revealing is that although the language of the affirmative defense should make it difficult for employers to proceed, lower courts have frequently construed the defense more broadly so as to deny plaintiffs relief.[95] In another case—this one unanimous—the Supreme Court resolved a long-standing split in the circuits by holding that the age discrimination statute permitted disparate impact claims, while creating a very loose standard for employers to justify their practices.[96]

Viewed in their entirety, the cases decided after 1991 reveal a decidedly different Supreme Court from the one that prompted passage of the CRA. The current Court seems more moderate and less hostile to employment discrimination plaintiffs and remarkably protective of the right to be free from retaliation, but at the same time continues to implement its own preferences when it matters the most. As a matter of positive political theory, the Court has responded not with timidity but in a strategically sophisticated fashion, and most of its decisions have remained in force. In other words, the CRA provided a meaningful but not total restraint on the Court’s impulses.

Although the CRA appears to have restrained the Supreme Court, it has had significantly less force in the lower courts. While I will not go into great detail to demonstrate the hostility to employment discrimination claims at the appellate level, I will highlight three different indicators. One has already been discussed, and that is the number of cases in which the Supreme Court unanimously reversed lower courts. In addition, appellate courts have created a number of legal doctrines that make it more difficult for plaintiffs to prove their cases. Many of the doctrines are evidentiary in nature, but all of them make it more, rather than less, difficult for plaintiffs to prevail. These doctrines include the creation of a fourth element of the prima facie case that requires plaintiffs (in some circuits) to prove that there is a similarly situated individual who was treated differently, with strict requirements governing who will satisfy the requirement; the stray remarks doctrine; and the same actor inference.[97] Equally important, no evidentiary rule or legal doctrine has arisen that favors plaintiffs, with the possible exception of some of the emerging case law regarding mixed-motives claims.[98]

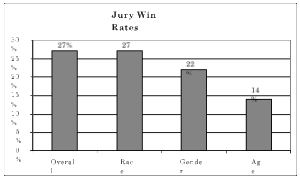

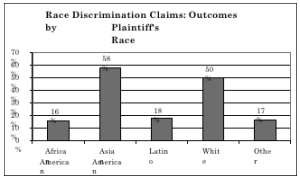

Perhaps the strongest indicator of the difficulty plaintiffs face in lower courts is revealed by the many studies that have documented low success rates both at trial and on appeal. In her Symposium contribution, Professor Wendy Parker surveys the studies,[99] and I will only add a brief summary of my own. The various studies are all consistent in their findings—more employment discrimination cases go to trial than do other kinds of cases, but plaintiffs typically have a lower success rate. Plaintiffs succeed in somewhere between 35–40% of their cases tried before a jury, with a significantly lower success rate before a judge.[100] Even though most cases are now tried before juries, this latter finding is important because judges handle the pre- and post-trial motions, and plaintiffs tend to have a low success rate in defending summary judgment motions.[101] The data also demonstrate that employment discrimination plaintiffs fare worse than other civil plaintiffs both at trial and on appeal.[102]

It might be that the lower success rates reflect weaker cases, but it is not at all clear why this might be so. There is no clear reason why employees would file weaker cases, particularly given the filtering process that requires individuals to first proceed through the federal EEOC or the state analogue.[103] While there may be a higher number of pro se plaintiffs, the absolute number remains very small, and very few ever get to trial.[104] The settlement values are also typically modest,[105] so these cases should not be particularly attractive to profit-motivated attorneys, though the availability of attorney’s fees might be an additional incentive. Nevertheless, if the monetary value is not the inducement, the prospect of success surely should be, and again, unless the cases were worth significantly more, attorneys should have the same incentives to bring strong employment discrimination claims as they would to bring other civil cases.[106] It also strikes me as problematic to assume it is the cases rather than the judges that drive the disparate results—it seems to me the burden should be on explaining what those differences might be rather than simply suggesting employment discrimination cases are less meritorious. Indeed, the “blame the cases” mentality—which arises in most presentations of the data—mirrors the judicial hostility to employment discrimination cases.

Although it may come as a surprise to some that in the context of employment discrimination cases the lower courts now appear to be more conservative than the Supreme Court, this is less of a surprise within the positive political theory framework. Congressional action is almost always aimed at the Supreme Court rather than lower courts, and as a result, Congress poses less of a threat to the lower courts. Instead, the Supreme Court plays the primary restraining role on the appellate courts, and it may be that the chance of review and reversal is so low as to pose only a limited constraint. At the same time, the prospect of congressional reversal also seems quite low, and it is not clear why one would pose a greater restraint than the other. It may be that the difference lies in the assumptions behind the process: Supreme Court review is a normal part of the appellate process, whereas congressional action is an extraordinary and public process that typically is directed at cases of greater magnitude.

Whatever the reason, the problem for plaintiffs pursuing employment discrimination claims lies primarily in the lower courts rather than in the Supreme Court; this also makes the prospect for meaningful change more complicated since congressional action is less likely to reshape judicial approaches in the appellate courts. The Supreme Court might be able to prompt change, but, outside of a handful of aberrational cases, that does not seem to be the Court’s interest. I think there is little question that the current Supreme Court remains fundamentally conservative and is not likely to have a preference for greater plaintiff success in the lower courts.

Conclusion

The CRA not only reversed a series of decisions but also prompted the Supreme Court to change its interpretive position. Plaintiffs have fared considerably better in the last two decades than they did in the period immediately preceding the passage of the CRA. But the Supreme Court has clearly not entirely relented, as it continues to reach conservative results in the cases in which it appears to have the strongest preferences. Close decisions continue to trend for defendants without much variation, whereas the decisions that side with plaintiffs are now most commonly unanimous, and often short, decisions. Yet, as noted, the real obstacles for plaintiffs have simply moved to the appellate courts, in which plaintiffs now continually face hostile forums, ones that the Supreme Court is generally willing to accept and that avoid the glare of Congress. So while the Supreme Court has become a more favorable forum for employment discrimination plaintiffs, conditions on the whole have not significantly improved.

| Case | Outcome | Margin |

| Harris v. Forklift Sys., 510 U.S. 17 (1993) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| McKennon v. Nashville Banner Publ’g Co., 513 U.S. 352 (1995) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| O’Connor v. Consol. Coin Caterers Corp., 517 U.S. 308 (1996) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Walters v. Metro. Educ. Enters., Inc., 519 U.S. 202 (1997) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Robinson v. Shell Oil, 519 U.S. 337 (1997) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Oubre v. Entergy Operations, Inc., 522 U.S. 422 (1998) | Pl. | 6-3 |

| Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Servs., 523 U.S. 75 (1998) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Burlington Indus., Inc. v. Ellerth, 524 U.S. 742 (1998) | Pl. | 7-2 |

| Faragher v. City of Boca Raton, 524 U.S. 775 (1998) | Pl. | 7-2 |

| West v. Gibson, 527 U.S. 212 (1999) | Pl. | 5-4 |

| Kolstad v. Am. Dental Ass’n, 527 U.S. 526 (1999) | Pl. | 9-0 & 5-4 |

| Reeves v. Sanderson Plumbing Prods., Inc., 530 U.S. 133 (2000) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Pollard v. E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., 532 U.S. 843 (2001) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| EEOC v. Waffle House, Inc., 534 U.S. 279 (2002) | Pl. | 6-3 |

| Edelman v. Lynchburg Coll., 535 U.S. 106 (2002) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Nat’l R.R. Passenger Corp. v. Morgan, 536 U.S. 101 (2002) | Pl. | 9-0 & 5-4 |

| Clackamas Gastroenterology Assocs., P.C. v. Wells, 538 U.S. 440 (2002) | Pl. | 7-2 |

| Desert Palace, Inc. v. Costa, 539 U.S. 90 (2003) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Jones v. R.R. Donnelley & Sons Co., 541 U.S. 369 (2004) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Smith v. City of Jackson, 544 U.S. 228 (2005) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Ash v. Tyson Foods, Inc., 546 U.S. 454 (2006) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Arbaugh v. Y&H Corp., 546 U.S. 500 (2006) | Pl. | 8-0 |

| Burlington N. & Santa Fe Ry. Co. v. White, 548 U.S. 53 (2006) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Fed. Express Corp. v. Holowecki, 552 U.S. 389 (2008) | Pl. | 7-2 |

| CBOCS W., Inc. v. Humphries, 553 U.S. 442 (2008) | Pl. | 7-2 |

| Gomez-Perez v. Potter, 553 U.S. 474 (2008) | Pl. | 6-3 |

| Meacham v. Knolls Atomic Power Lab., 554 U.S. 84 (2008) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Crawford v. Metro. Gov’t of Nashville & Davidson Cnty., 129 S. Ct. 846 (2009) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Lewis v. City of Chi., 130 S. Ct. 2191 (2010) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Sprint/United Mgmt. Co. v. Mendelsohn, 552 U.S. 379 (2008) | None | 9-0 |

| Hazen Paper Co. v. Biggins, 507 U.S. 604 (1993) | Def. | 9-0 |

| St. Mary’s Honor Ctr. v. Hicks, 509 U.S. 502 (1993) | Def. | 5-4 |

| Landgraf v. USI Film Prods., 511 U.S. 244 (1994) | Def. | 8-1 |

| Rivers v. Roadway Express, Inc., 511 U.S. 298 (1994) | Def. | 8-1 |

| Comm’r v. Schleier, 515 U.S. 323 (1995) | Def. | 6-3 |

| Clark Cnty. Sch. Dist. v. Breeden, 532 U.S. 268 (2001) | Def. | 9-0 |

| Gen. Dynamics Land Sys. v. Cline, 540 U.S. 581 (2004) | Def. | 6-3 |

| Pa. State Police v. Suders, 542 U.S. 129 (2004) | Def. | 8-1 |

| Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 550 U.S. 618 (2007) | Def. | 5-4 |

| Ky. Ret. Sys. v. EEOC, 554 U.S. 135 (2008) | Def. | 5-4 |

| AT&T Corp. v. Hulteen, 129 S. Ct. 1962 (2009) | Def. | 7-2 |

| Gross v. FBL Fin. Servs., Inc., 129 S. Ct. 2343 (2009) | Def. | 5-4 |

| Ricci v. DeStefano, 129 S. Ct. 2658 (2009) | Def. | 5-4 |

| Case | Outcome | Margin |

| Cal. Fed. Sav. & Loan Ass’n v. Guerra, 479 U.S. 272 (1987) | Pl. | 6-3 |

| United States v. Paradise, 480 U.S. 149 (1987) | Pl. | 5-4 |

| Johnson v. Transp. Agency, 480 U.S. 616 (1987) | Pl. | 6-3 |

| St. Francis Coll. v. Al-Khazraj, 481 U.S. 604 (1987) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S. 656 (1987) | Def. | 6-3 |

| EEOC v. Commercial Office Prods. Co., 486 U.S. 107 (1988) | Pl. | 6-3 |

| Watson v. Fort Worth Bank & Trust, 487 U.S. 977 (1988) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989) | Def. | 6-3 |

| Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio, 490 U.S. 642 (1989) | Def. | 5-4 |

| Martin v. Wilks, 490 U.S. 755 (1989) | Def. | 5-4 |

| Lorance v. AT&T Techs., Inc., 490 U.S. 900 (1989) | Def. | 5-3 |

| Patterson v. McClean Credit Union, 491 U.S. 164 (1989) | Def. | 5-4 |

| Indep. Fed’n of Flight Attendants v. Zipes, 491 U.S. 754 (1989) | Def. | 6-2 |

| Pub. Emps. Ret. Sys. v. Betts, 492 U.S. 158 (1989) | Def. | 7-2 |

| Univ. of Pa. v. EEOC, 493 U.S. 182 (1990) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| W. Va. Hosps., Inc. v. Casey, 499 U.S. 83 (1991) | Def. | 6-3 |

| Int’l Union v. Johnson Controls, Inc., 499 U.S. 187 (1991) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| EEOC v. Arabian Am. Oil Co., 499 U.S. 244 (1991) | Def. | 6-3 |

| Stevens v. Dep’t of Treasury, 500 U.S. 1 (1991) | Pl. | 8-1 |

| Gilmer v. Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp., 500 U.S. 20 (1991) | Def. | 7-2 |

| Astoria Fed. Sav. & Loan Ass’n v. Solimino, 501 U.S. 104 (1991) | Pl. | 9-0 |

| Gregory v. Ashcroft, 501 U.S. 452 (1991) | Def. | 6-3 |

* Samuel Tyler Research Professor of Law, George Washington University Law School. An earlier version of this Article was presented at a Symposium held at Wake Forest University School of Law, where I benefitted from the comments and conversations I had at the time. Particular thanks to Professor Wendy Parker for the invitation to participate and for very helpful suggestions.

The NAACP Legal Defense Fund sought and obtained participation as amicus curiae by 47 of the 50 states, the American Bar Association, and a bipartisan group of 66 Senators and 119 Representatives. It sought also the participation of the executive branch as amicus, but the administration decided not to participate.

Id. at 952 n.18; see also Al Kamen, Administration Won’t Argue Rights Case: Solicitor General Upsets Conservatives, Wash. Post, June 24, 1988, at A1. “The Government had filed a brief on Patterson’s behalf on initial argument which had assumed the validity of Runyon’s interpretation of § 1981, and, given that premise, had supported Patterson’s position that racial harassment could give rise to a valid § 1981 claim against a private employer.” Livingston & Marcosson, supra, at 952 n.18.

No statements other than the interpretive memorandum appearing at Vol. 137 Congressional Record S 15276 (daily ed. Oct. 25, 1991) shall be considered legislative history of, or relied upon in any way as legislative history in construing or applying, any provision of this Act that relates to Wards Cove—Business necessity/cumulation

/alternative business practice.

Civil Rights Act of 1991, Pub. L. No. 102-166, § 105(b), 105 Stat. 1071, 1075 (codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1981 (2006)).

By: Melissa Hart*

When Congress passed the 1991 Civil Rights Act (“1991 Act”), the new disparate impact provisions of the law were heralded as a victory for civil rights plaintiffs.[1] After all, the statute was enacted in response to the Supreme Court’s cramped, “near-death”[2] interpretation of disparate impact law in Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio.[3] The new law was a legislative sanctioning of the judicially created doctrine that facially neutral policies may still violate Title VII if their impact falls too heavily on a protected class and they cannot be justified as “business necessity.”[4] This aspect of antidiscrimination law was viewed by many as the best chance for challenging the “built-in headwinds” that continue to keep equal employment opportunity out of reach.[5]

Twenty years later, it is not at all clear that the disparate impact provisions of the 1991 Act have delivered their promised victory. Disparate impact claims are very rarely successful.[6] Moreover, the Supreme Court’s 2009 decision in Ricci v. DeStefano,[7] while technically a disparate treatment case, may well have done as much to eviscerate disparate impact’s potential as Wards Cove did twenty years earlier.[8] The decisions share many common themes: both have particularly unusual facts, both reveal the Court’s willingness to eschew procedural limitations to reach substantive questions not properly before the Court, and both show sharp divisions among the Justices. Perhaps most importantly, both reveal deep skepticism on the part of many Justices about the underlying premise of disparate impact law: that racial inequalities persist because of continued systemic and institutional biases that can and should be addressed.

But while Wards Cove spoke directly to standards of proof for litigating disparate impact claims, Ricci’s consequences will be felt on the compliance side of the law. These consequences may be especially dire because disparate impact was always most useful for its deterrence and compliance effects. Even though plaintiffs have only rarely succeeded in bringing disparate impact claims, the powerful statement of equality inherent in such claims—embodied in the principle that employers should not use facially neutral practices that create a disparate impact unless there is a true business necessity to do so—is an essential message of antidiscrimination law. And the possibility of disparate impact litigation prompts companies to evaluate their own practices and to make internal adjustments that make employment policies more fair.

This Article begins, in Part I, by considering the early potential of disparate impact law, and the Supreme Court’s response in Wards Cove. Part II evaluates how much the Civil Rights Act of 1991 actually promised discrimination plaintiffs and examines how disparate impact litigation developed in subsequent years. Part III considers the Court’s decision in Ricci and its consequences for the voluntary compliance efforts that disparate impact law has encouraged.

When the Supreme Court in 1971 first recognized disparate impact as a legal theory under Title VII, the Court explained that the “absence of discriminatory intent does not redeem employment procedures or testing mechanisms that operate as ‘built-in headwinds’ for minority groups and are unrelated to measuring job capability.”[9] Forty years later, it is the built-in headwinds of a Supreme Court skeptical of—perhaps even hostile to—the goals of disparate impact theory that pose the greatest challenge to continued movement toward workplace equality.

The disparate impact cause of action was first recognized by the Supreme Court as a necessary element of Title VII in order for that statute to truly reach all employment practices that operated to deny equal opportunity. In Griggs v. Duke Power Co., the Supreme Court explained that Title VII “proscribes not only overt discrimination but also practices that are fair in form, but discriminatory in operation. The touchstone is business necessity. If an employment practice that operates to exclude Negroes cannot be shown to be related to job performance, the practice is prohibited.”[10] The Griggs Court understood that intentional discrimination was not only hard to prove but was also only part of the problem in workplaces that had for so long unthinkingly imposed rules that disadvantaged women and people of color.[11]

During the 1970s and 1980s, disparate impact theory was used to challenge the kinds of “objective” employment criteria—primarily standardized test requirements—that had been disputed in Griggs.[12] Importantly though, it also encouraged employer compliance efforts and even voluntary affirmative action programs.[13] Lawyers and human resource professionals advised companies to carefully evaluate their job requirements and to “initiate and implement more creative selection and training procedures.”[14] And many civil rights advocates viewed disparate impact theory as a driving force behind Title VII’s success as a “major instrument of social progress.”[15]

But disparate impact faced vocal criticism from the beginning.[16] Courts and commentators worried that

acceptance of the idea that discrepancies between racial composition of the community and the plant or department alone make out a prima facie case of discrimination leads inevitably toward a narrowing of the Court’s options in fashioning a remedy. If the problem is to be demonstrated by the mere fact of a discrepancy, then the solution logically must amount to an order to bring the employment statistics into line with the population statistics . . . .[17]

This fear, that employers would simply engage in quota hiring to avoid disparate impact liability, was a constant threat to disparate impact law’s development.

Five years after deciding Griggs, the Court concluded that the disparate impact theory was not available to plaintiffs bringing constitutional claims; instead, the Equal Protection Clause is violated only by intentionally discriminatory conduct.[18] Indeed, the Washington v. Davis majority revealed considerable skepticism about disparate impact as a theory of discrimination, announcing that, “[a]s an initial matter, we have difficulty understanding how a law establishing a racially neutral qualification for employment is nevertheless racially discriminatory and denies ‘any person . . . equal protection of the laws’ simply because a greater proportion of Negroes fails to qualify than members of other racial or ethnic groups.”[19] This rejection of disparate impact theory in constitutional analysis put disparate impact claims on shaky ground by creating a distinction between “true” discrimination and claims of disparate impact.[20]

The question of whether disparate impact effectively required employers to implement quotas to avoid liability was presented to the Supreme Court as early as 1977.[21] The concern expressed by critics of impact theory was that, if plaintiffs can make out a prima facie case of disparate impact discrimination merely by showing that an employer’s hiring or promotion policies lead to statistical underrepresentation of a protected class, then defendants will have an incentive to avoid liability by simply ensuring that their workforce does not show that statistical underrepresentation.[22] This is troubling, critics argue, because Title VII specifically provides that the statute shall not be interpreted to require any kind of proportional representation.[23]

In International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States, the Supreme Court dismissed the concern that reliance on statistical proof will lead to race-based quota hiring.[24] In a disparate treatment case, statistics are probative because they are “often a telltale sign of purposeful discrimination.”[25] In disparate impact litigation, statistical disparities push the employer to justify its business practices—to explain why the practice that is creating the disparity is actually necessary for the workplace. Liability will not flow from statistical disparities alone, but from reliance on business practices that are unnecessary and that impose a disproportionate disadvantage on women or people of color.[26]

The tension between those who viewed disparate impact as the best hope for challenging continued workplace inequality and those who viewed impact theory as an illegal directive to implement hiring quotas came to a head in Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio. In Wards Cove, the Supreme Court confronted a disparate impact challenge to the racially segregated world of salmon canneries in Alaska.[27] At the two canneries that were the subject of the litigation, jobs were classified as “cannery” (unskilled) and “noncannery” (skilled).[28] The cannery jobs were filled almost entirely by Filipinos and Alaska Natives who were either hired through one union or resided in villages near the canneries.[29] The noncannery jobs, which paid more than the cannery positions, were filled predominantly by whites who were recruited in Washington and Oregon.[30] Cannery employees lived in separate dormitories and ate in separate dining halls from the noncannery employees.[31] Justice Blackmun described these working conditions in his dissenting opinion:

The salmon industry as described by this record takes us back to a kind of overt and institutionalized discrimination we have not dealt with in years: a total residential and work environment organized on principles of racial stratification and segregation . . . . This industry long has been characterized by a taste for discrimination of the old-fashioned sort: a preference for hiring nonwhites to fill its lowest level positions, on the condition that they stay there.[32]

In 1974, fifteen years before the case would reach the Supreme Court, a class of nonwhite cannery workers brought suit challenging a broad range of the companies’ employment policies: nepotism, separate hiring channels for cannery and noncannery positions, a rehire preference, a practice of not promoting from within, an English language requirement, no posting for noncannery positions, and a lack of objective hiring criteria.[33] The plaintiffs contended that these practices “were responsible for the racial stratification of the work force and had denied them and other nonwhites employment as noncannery workers on the basis of race.”[34] They claimed both disparate impact and disparate treatment violations of Title VII.[35] The Wards Cove litigation had a tortuous procedural history during which the lower courts rejected the plaintiffs’ disparate treatment claims but permitted the impact claims.[36] The dispute arrived at the Supreme Court on an interlocutory appeal, and the Court took the case as an opportunity to make a number of pronouncements about Title VII’s disparate impact standards.[37]

In a sharply divided opinion, the Court first criticized the lower court’s comparison of the percentage of cannery positions held by nonwhites with the percentage of noncannery positions held by nonwhites.[38] The relevant comparison, the majority explained, is between the percentage of job holders and the percentage of qualified applicants for those jobs.[39] In telling its story about what qualifications were relevant to that comparison, the Wards Cove majority focused exclusively on the noncannery jobs that required special skills, such as accountants, doctors, and other professionals.[40] To compare those jobs to the unskilled positions held by cannery workers was to hold the employer responsible for differences between the two labor pools that had nothing to do with the employers’ policies and practices: “If the absence of minorities holding such skilled positions is due to a dearth of qualified nonwhite applicants (for reasons that are not the petitioners’ fault), petitioners’ selection methods or employment practices cannot be said to have had a ‘disparate impact’ on nonwhites.”[41]

The Court went on to hold that a plaintiff bringing a disparate impact challenge must identify with specificity what particular employment practice caused the complained-of disparate impact.[42] Plaintiffs cannot make out a prima facie case of disparate impact simply by pointing to significant racial disparities in workforce composition.[43] The Court concluded that “[t]o hold otherwise would result in employers being potentially liable for ‘the myriad of innocent causes that may lead to statistical imbalances in the composition of their work forces.’”[44]

Finally, and most controversially, the Court reversed twenty years of disparate impact law and concluded that an employer seeking to explain racial disparity with a “business necessity” will not have to demonstrate that the practice in question is “essential” or “indispensible.”[45] Forcing the employer to meet this burden, the majority explained, imposes too onerous a standard, and “would result in a host of evils.”[46] This “host of evils” is the possibility that employers will engage in quotas or hiring goals in order to avoid disparate impact liability.[47] Instead, the Court held that an employer facing a charge of disparate impact discrimination would not have to “demonstrate” anything, in the sense of meeting a burden of proof.[48] Instead of being an affirmative defense—which “business necessity” had been since Griggs—the majority concluded that the employer’s burden should be merely a burden of production.[49] The disparate impact plaintiff would be required to demonstrate that the challenged practice was not a business necessity.[50] Moreover, the Wards Cove majority significantly weakened the “business necessity” threshold, concluding that an employer’s challenged policy need only serve “the legitimate employment goals of the employer.”[51]

Wards Cove produced two impassioned dissents, one penned by Justice Blackmun[52] and the other by Justice Stevens.[53] Blackmun’s dissent observed that the legal changes wrought by the decision “essentially immunize[d] . . . from attack” the range of practices that entrenched “racial stratification and segregation” in the salmon industry.[54] Justice Stevens’s dissent accused the majority of “[t]urning a blind eye to the meaning and purpose of Title VII,” when it “perfunctorily reject[ed] a longstanding rule of law and underestimate[d] the probative value of evidence of a racially stratified work force.”[55] One of the most striking things about the three opinions—the majority and the two dissents—is what radically different meaning the dissenting Justices took from the facts of the case than did the members of the five-Justice majority. As Justice Blackmun concluded, “One wonders whether the majority still believes that race discrimination—or, more accurately, race discrimination against nonwhites—is a problem in our society, or even remembers that it ever was.”[56]

Justice Stevens’s dissent began by observing that this case had very unusual and complicated facts and should not have been used to rewrite the law.[57] He went on to detail the ways in which the Wards Cove majority broke from the settled law in disparate impact cases.[58] A substantial part of the dissent was occupied with challenging the majority’s view of how to think about the statistical evidence offered to the lower courts.[59] Where the majority disregarded the segregation of the noncannery and cannery workforces as being irrelevant comparisons, Justice Stevens argued that in the “unique industry” of Alaskan salmon canneries, there are key elements that make the comparison of these two groups particularly appropriate.[60] He presented a very different picture of the “skilled” noncannery positions filled almost entirely by white employees; instead of focusing on the doctors and accountants that occupy the majority, he pointed out that the “skills” required for many of those positions included only things like English literacy, typing, good health, and possession of a driver’s license.[61] Moreover, Justice Stevens pointed out that one of the most important job qualifications for both cannery and noncannery employees in this industry was a willingness to be available for and to accept seasonal employment.[62] That important variable makes the comparison between these two groups of employees arguably more relevant than any other comparison and certainly as relevant as a comparison of noncannery workers with the general labor force.

The fundamental difference between the stories told by the dissents and the story told by the majority is a crucial element of Wards Cove. The majority saw the facts through a lens of skepticism about—even perhaps hostility to—the reach of disparate impact theory. The absolute segregation of the salmon industry did not worry the Justices in the majority because they viewed that segregation as occurring naturally, unrelated to policy choices being made by the employer. For the dissenting Justices, the “unsettling resemblance to aspects of a plantation economy”[63] was the major concern, and the lens through which the applicable legal standards were considered. Wards Cove revealed how completely divergent views about disparate impact law mirrored similar debates about affirmative action. In both contexts, one sees the substantial divide between those who view workplace discrimination against people of color as a continuing serious problem and those who believe that antidiscrimination laws have themselves become a source of unfair treatment of white workers.[64]

The Civil Rights Act of 1991 was an emphatic and hard-fought rejection of several 1989 Supreme Court decisions—most especially of Wards Cove’s changes to disparate impact law.[65] The bill that passed and that was signed by President George H. W. Bush was heralded as a victory for plaintiffs in part because of the process that led to its passage. The bill was first vetoed, and the subsequent year-long negotiations ended with what many called a “capitulation” by a Republican White House to the demands of civil rights leaders that disparate impact law remain a viable litigation theory.[66] The core of the debate that shaped the relevant provisions of the legislation was about the relationship between disparate impact and quotas.

The 1991 codification of disparate impact explicitly returned the law, in certain respects, to its pre-Wards Cove status.[67] In particular, section 703(k) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, amended by section 105(a) of the 1991 Act, now specifies that “business necessity” is an affirmative defense, which the defendant carries the burden of demonstrating after the plaintiff has made out a prima facie case that an employer practice disproportionately impacts protected employees.[68] “Business necessity,” which the Wards Cove majority had described as anything consistent with “legitimate employment goals,”[69] is defined in the new section 703(k) as “job related for the position in question and consistent with business necessity.”[70] The 1991 Act also specifically returned the meaning of “alternative employment practice” to that which it had been under “the law as it existed on June 4, 1989.”[71] As to the prima facie case, which the Supreme Court had said required identification of a specific employment practice,[72] Congress provided that a plaintiff typically does have to demonstrate a particular practice that causes a disparate impact, but the legislature offered an exception for circumstances in which the plaintiff can demonstrate “that the elements of a [defendant’s] decisionmaking process are not capable of separation for analysis.”[73] In that circumstance, “the decisionmaking process may be analyzed as one employment practice.”[74]

Given the battle over disparate impact that led to the 1991 Civil Rights Act, it would be reasonable to imagine an increase in the number of disparate impact cases following the statute’s enactment. In fact, however, there was no surge in the number of disparate impact suits filed after 1991. And, as Michael Selmi’s 2006 empirical evaluation of disparate impact cases demonstrated, plaintiffs had significantly more success with disparate impact claims before 1991 than after.[75]

There are a number of possible explanations for the relatively small number of disparate impact claims in the federal courts. Perhaps most significantly, the 1991 Act added compensatory and punitive damages to Title VII’s remedial arsenal, but only for claims of intentional discrimination.[76] This change created substantial incentives for plaintiffs to frame their suits as disparate treatment rather than disparate impact claims. Further, although the 1991 Act was quite explicit in rejecting Wards Cove, the statute still left considerable uncertainty about core interpretive questions—including what constitutes an “employment practice” subject to challenge and precisely what “business necessity” means—in disparate impact litigation. And importantly, the number of disparate impact claims was lower by the 1990s because disparate impact theory was doing what it was in large part intended to do: encourage employers to develop internal practices that did not have a disparate impact on protected classes. Indeed “[t]he disparate impact standard . . . triggered reconsideration of a wide range of promotion practices and other devices that failed to accurately measure and predict candidates’ job performance.”[77] By 1991, twenty years after Griggs, employer practices that caused obvious disparate impact without any business justification had been eliminated in many workplaces through employers’ own internal compliance efforts.

Just as the promise of the 1991 Act might have been more rhetorical than substantive for potential disparate impact litigation, the perils that opponents saw lurking behind disparate impact theory did not emerge in the wake of the new law. There is absolutely no evidence to suggest that the newly codified disparate impact theory led employers to adopt quotas or to lower their employment standards. But the fear that potential disparate impact liability might lead employers to adopt hiring quotas—and more generally the anxiety that antidiscrimination laws were themselves prompting discrimination against white employees—has not diminished.

Twenty years and twenty days after announcing its ruling in Wards Cove, the Supreme Court issued another sharply divided set of opinions in Ricci v. DeStefano.[78] Ricci was a disparate treatment case, but the allegation of disparate treatment stemmed from the City of New Haven’s effort to avoid disparate impact liability.[79] A five-Justice majority concluded that the City had engaged in intentional discrimination against white firefighters when it declined to certify the results of a promotion test that had a disparate impact on minority firefighters.[80]

Ricci shared a number of similarities with the Wards Cove decision. One of the most immediately notable is that in both cases the Court’s majority ignored basic procedural norms that are supposed to constrain the Supreme Court in order to reach its preferred outcome. In Wards Cove, the Court significantly altered disparate impact law in a case that came to it on interlocutory review, and the dissent was sharply critical of what it saw as procedural impropriety.[81] Similarly in Ricci, the dissenting Justices observed that the majority was departing from the Court’s usual procedural rules by not simply reversing the summary judgment granted and upheld below, but actually reviewing the record and granting summary judgment for the other side.[82] The willingness to ignore procedural norms gives both opinions an aura of “judicial activism” that heightens the sense that both are part of a political debate in which statutory interpretation is just one argument.

Wards Cove and Ricci are also notable for their complex facts, and for the widely different view of the facts offered by the majority and the dissent in each case. The highly contested facts in Ricci made especially surprising the majority’s decision to grant summary judgment based on the record as it stood at the Supreme Court.[83]

In 2003, the City of New Haven administered a written test as part of the process for selecting promotion-eligible employees for officer positions in the fire department.[84] The test was developed to account for sixty percent of the promotion process because the City’s decades-old contract with the firefighter’s union provided that promotion would be based sixty percent on a written exam and forty percent on an oral exam.[85] The City charter provided that, after the exam was administered, the Civil Service Board would rank applicants, creating a list from which vacancies would be filled.[86] Candidates had to be chosen from among the top three scorers on the list, and the list would remain valid for two years.[87] Seventy-seven candidates completed the 2003 lieutenant examination and forty-one candidates completed the examination for promotion to captain.[88] The results on both examinations showed significant racial disparities for both African-American and Latino test takers sufficient to make out a prima facie case of disparate impact under Title VII.[89]

As soon as the exam results were made publicly available, “[s]ome firefighters argued the tests should be discarded because the results showed the test to be discriminatory. They threatened a discrimination lawsuit if the City made promotions based on the tests. Other firefighters said the exams were neutral and fair. And they, in turn, threatened a discrimination lawsuit” if the City did not certify the results.[90] At this point, the City found itself between the proverbial rock and a hard place.

In January 2004, the Civil Service Board met to decide whether to certify the results of the exam.[91] At the beginning of the meeting, the City’s director of Human Resources informed the board that she believed the exam created a “significant disparate impact” on test takers.[92] Over the course of five meetings, the Civil Service Board heard testimony from the person who had developed the test for the City, additional firefighters, New Haven community members, other professional test developers, individuals employed in fire departments in other cities, the City’s legal counsel, and a psychologist from Boston College, among others.[93] At the close of these meetings, the Civil Service Board voted on whether to certify the results. With one member recused, the remaining four board members were deadlocked, two to two, on whether to certify; consequently, the list was not certified.[94]

Following the decision not to certify the results, seventeen white firefighters and one Hispanic firefighter filed suit, alleging, among other claims, that the decision not to certify was an act of intentional race discrimination.[95] In district court, the City successfully argued that the Civil Service Board’s good-faith belief that certifying the exam would expose it to liability for disparate impact discrimination shielded it from liability for disparate treatment, and was granted summary judgment.[96] The Supreme Court rejected this argument, concluding that “there is no genuine dispute that the examinations were job-related and consistent with business necessity,”[97] and granted summary judgment for the firefighters.[98] For the majority, the story—the undisputed and indisputable story—of what happened in New Haven was this:

The record in this litigation documents a process that, at the outset, had the potential to produce a testing procedure that was true to the promise of Title VII: No individual should face workplace discrimination based on race. Respondents thought about promotion qualifications and relevant experience in neutral ways. They were careful to ensure broad racial participation in the design of the test itself and its administration. As we have discussed at length, the process was open and fair. The problem, of course, is that after the tests were completed, the raw racial results became the predominant rationale for the City’s refusal to certify the results.[99]

This understanding of what happened in New Haven rests on a number of much contested assumptions about the neutrality and fairness of the City’s test and the process used to design it. The majority simply disregarded the catalog of contested factual questions. With these blinders on, it could perceive the statistically significant disparate impact of the test as legally irrelevant.

The Ricci dissent told a very different story. The dissent described a long history of race discrimination in the New Haven Fire Department and pointed to portions of the record that suggested that the challenged test was significantly more problematic than the majority’s recitation of the facts suggested.[100] While the majority lauded the test-development process, the dissent pointed out that there was no determination before hiring the test writer of what kind of test would best evaluate candidates for promotion.[101] In fact, the City didn’t consider any other testing mechanism; didn’t question its use of a decades-old decision to weight the written exam sixty percent and the oral exam forty percent; and didn’t vet the written exam with any experienced local firefighters.[102]

Indeed, only after the test was administered, and the significant adverse impact became apparent, did the City seem to realize the range of flaws in the test and refer the question to the Civil Service Board.[103] At this point, too, the dissenting opinion demonstrates that a very different story can be read in the record than the majority’s view that only statistical racial disparities mattered in the Civil Service Board’s process; the record included evidence that Civil Service Board members understood that “their principal task was to decide whether they were confident about the reliability of the exams: Had the exams fairly measured the qualities of a successful fire officer despite their disparate results? Might an alternative examination process have identified the most qualified candidates without creating such significant racial imbalances?”[104]