By Eric Jones

On December 18, 2015, the Fourth Circuit issued a published opinion in the criminal case United States v. Stover. Lavelle Stover was convicted of possession of a firearm as a felon, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(1). At trial, Stover motioned to suppress the firearm that he discarded in front of his vehicle, but the motion was denied. On appeal Stover argued that the firearm should have been suppressed as the product of an illegal seizure under the Fourth Amendment. The Fourth Circuit affirmed his conviction.

The Arrest and Trial

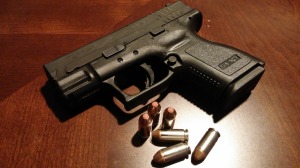

In the early morning hours of March 13, 2013, police noticed Stover sitting in a vehicle that was double-parked in a small private parking lot. When they returned several minutes later and saw that Stover was still double-parked, the officers decided to approach the vehicle because there had recently been several violent robberies in the area. The uniformed officers activated their emergency lights and aimed a spotlight on Stover’s vehicle as they pulled in to block the car in the parking lot. As the officers exited the patrol car, Stover exited his vehicle and made his way to the front of his car. He completely ignored the officers’ ordering him to stop and return to his vehicle. Stover tossed a loaded nine millimeter handgun into the grass in front of his vehicle. One officer proceeded along the right side of Stover’s vehicle and confronted him with his gun drawn, believing that Stover was preparing to run. At that point Stover silently complied with the officers’ orders and returned to his vehicle.

At trial in the District Court for the District of Maryland, Stover motioned to suppress the handgun on the theory that it was the product of an illegal seizure under the Fourth Amendment. The District Court found that Stover had not submitted to police authority until after abandoning the firearm, and thus the protections Fourth Amendment did not apply. The firearm was entered into evidence, and Stover was convicted by a jury and sentenced to 57 months in prison. Stover filed a timely appeal.

The Fourth Amendment’s Protections Against Illegal Seizure

As the Fourth Circuit explained, the moment that Stover was seized is vital to determine whether or not the firearm should have been suppressed. If the officers had reasonable suspicion to stop Stover, the Fourth Amendment is not implicated and the weapon was properly entered. If there was not reasonable suspicion to stop the defendant, however, the Circuit Court explained that the exact circumstances of the stop are important to determine whether an illegal seizure has occurred. The Fourth Circuit applied a two-part test outlined in California v. Hodari D..

First, the Circuit Court asked whether the Fourth Amendment was implemented due to a show of authority by the officers. In order to determine whether a show of authority had occurred, the Supreme Court has explained that you must consider whether “in view of all the circumstances surrounding the incident, a reasonable person would have believed that he was not free to leave.” As applied here, the Fourth Circuit held that blocking in Stover’s car with a marked police car, activating the emergency lights, using their spotlight, and approaching Stover’s vehicle in uniform all clearly indicated that a show of force had been made, and thus the Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable seizures.

The second part of the two-part test in order to determine whether the firearm could be admitted into evidence asks precisely when the defendant was seized. The Fourth Circuit explained that after submitting to police authority, the Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable seizure. If the defendant has not capitulated to the police’s orders, however, there has been at most an “attempted seizure,” and the protections of the Fourth Amendment are not applicable until after the defendant has submitted. The Fourth Circuit explained that if a defendant is fleeing from the police, he has not submitted and thus anything he tosses to the side as he runs is not subject to the protections of the Fourth Amendment. If, however, the defendant has submitted (by being tackled, by stopping voluntarily, or any other submission), the Fourth Amendment applies to anything found on his person.

Stover Did Not Submit to the Officers until After Abandoning His Firearm

In this case, the Fourth Circuit held that Stover had not submitted to the officers until after abandoning the firearm, and thus the Fourth Amendment was not applicable. The Court relied on the fact that Stover exited his vehicle despite the flashing emergency lights and direct orders to remain in his vehicle. He then proceeded toward the front of his car, directly away from the officers, and did not indicate that he heard them or intended to comply. Only after abandoning his firearm and being confronted by the armed officer did Stover submit to their authority and follow their commands. Thus, because Stover was not seized until after he threw the handgun into the grass, he simply abandoned it and it was not seized by the police.

One Circuit Judge dissented in this case, arguing that Stover acquiesced to the officers’ orders by remaining on the scene and simply attempted to abandon his firearm while remaining under police control. If this were the case, the legality of the seizure would have been determined by whether or not the officers had reasonable suspicion to stop Stover. The majority, however, held that ignoring verbal orders and proceeding away from officers is not consistent with submitting to the police, and thus no seizure had yet occurred.

The Fourth Circuit Affirmed Stover’s Conviction

Because the evidence indicated that Stover had not submitted to the police and may have been attempting to flee when he abandoned the handgun, the Fourth Circuit affirmed that he had not been seized and thus his firearm was not the product of an illegal search or seizure. Because the handgun was properly admitted as evidence, therefore, the Circuit affirmed Stover’s conviction.