By Mary Catherine Young

Last month, an Azerbaijani journalist was forced to deactivate her social media accounts after receiving sexually explicit and violent threats in response to a piece she wrote about Azerbaijan’s cease-fire with Armenia.[1] Some online users called for the Azerbaijan government to revoke columnist Arzu Geybulla’s citizenship—others called for her death.[2] Days later, an Irish man, Brendan Doolin, was criminally charged for online harassment of four female journalists.[3] The charges came on the heels of a three-year jail sentence rendered in 2019 based on charges for stalking six female writers and journalists online, one of whom reported receiving over 450 messages from Doolin.[4] Online harassment of journalists is palpable on an international scale.

Online harassment of journalists abounds in the United States as well, with females receiving the brunt of the persecution.[5] According to a 2019 survey conducted by the Committee to Protect Journalists, 90 percent of female or gender nonconforming American journalists said that online harassment is “the biggest threat facing journalists today.”[6] Fifty percent of those surveyed reported that they have been threatened online.[7] While online harassment plagues journalists around the world, the legal ramifications of such harassment are far from uniform.[8] Before diving into how the law can protect journalists from this abuse, it is necessary to expound on what online harassment actually looks like in the United States.

In a survey conducted in 2017 by the Pew Research Center, 41 percent of 4,248 American adults reported that they had personally experienced harassing behavior online.[9] The same study found that 66 percent of Americans said that they have witnessed harassment targeted at others.[10] Online harassment, however, takes many shapes.[11] For example, people may experience “doxing” which occurs when one’s personal information is revealed on the internet.[12] Or, they may experience a “technical attack,” which includes harassers hacking an email account or preventing traffic to a particular webpage.[13] Much of online harassment takes the form of “trolling,” which occurs when “a perpetrator seeks to elicit anger, annoyance or other negative emotions, often by posting inflammatory messages.”[14] Trolling can encompass situations in which harassers intend to silence women with sexualized threats.[15]

The consequences of online harassment of internet users can be significant, invoking mental distress and sometimes fear for one’s physical safety.[16] In the context of journalists, however, the implications of harassment commonly affect more than the individual journalist themselves—free flow of information in the media is frequently disrupted due to journalists’ fear of cyberbullying.[17] How legal systems punish those who harass journalists online varies greatly both internationally and domestically.[18]

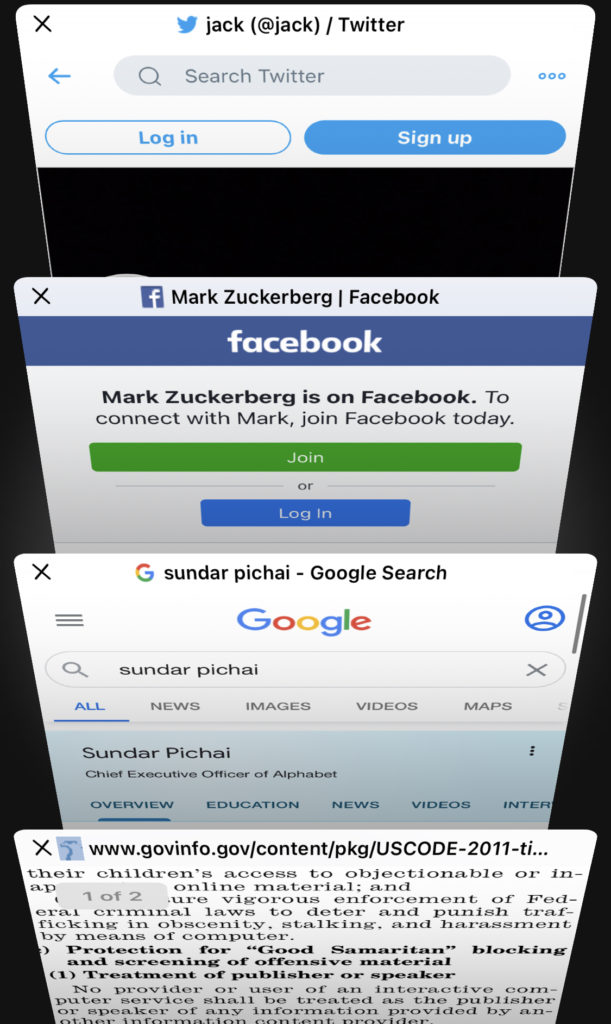

For example, the United States provides several federal criminal and civil paths to recourse for victims of online harassment, though not specifically geared toward journalists.[19] In terms of criminal law, provisions protecting individuals against cyber-stalking are included in 18 U.S.C. § 2261A, which criminalizes stalking in general.[20] According to this statute, “[w]hoever . . . with the intent to kill, injure, harass, intimidate, or place under surveillance with intent to . . . harass, or intimidate another person, uses . . . any interactive computer service . . . [and] causes, attempts to cause, or would be reasonably expected to cause substantial emotional distress to a person . . .” may be imprisoned.[21] In terms of civil law, plaintiffs may be able to allege defamation or copyright infringement claims.[22] For example, when the harassment takes the form of sharing an individuals’ self-taken photographs without the photographer’s consent, whether they are explicit or not, the circumstances may allow the victim to pursue a claim under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.[23]

Some states provide their own online harassment criminal laws, though states differ in whether the provisions are included in anti-harassment legislation or in their anti-stalking laws.[24] For example, Alabama,[25] Arizona,[26] and Hawaii[27] all provide for criminal prosecution for cyberbullying in their laws against harassment, whereas Wyoming,[28] California,[29] and North Carolina[30] include anti-online harassment provisions in their laws against stalking.[31] North Carolina’s stalking statute, however, was recently held unconstitutional as applied under the First Amendment after a defendant was charged for posting a slew of Google Plus posts about his bizarre wishes to marry the victim.[32] The North Carolina Court of Appeals decision in Shackelford seems to reflect a distinctly American general reluctance to interfere with individuals’ ability to freely post online out of extreme deference to First Amendment rights.

Other countries have taken more targeted approaches to legally protecting journalists from online harassment.[33] France, in particular, has several laws pertaining to cyberbullying and online harassment in general, and these laws have recently provided relief for journalists.[34] For example, in July 2018, two perpetrators were given six-month suspended prison sentences after targeting a journalist online.[35] The defendants subjected Nadia Daam, a French journalist and radio broadcaster, to months of online harassment after she condemned users of an online platform for harassing feminist activists.[36] Scholars who examine France’s willingness to prosecute perpetrators of online harassment against journalists and non-journalists alike point to the fact that while the country certainly holds freedom of expression in high regard, this freedom is held in check against other rights, including individuals’ right to privacy and “right to human dignity.”[37]

Some call for more rigorous criminalization of online harassment in the United States, particularly against journalists, to reduce the potential for online harassment to create a “crowding-out effect” that prevents actually helpful online speech from being heard.[38] It seems, however, that First Amendment interests may prevent many journalists from finding relief—at least for now.

[1] Aneeta Mathur-Ashton, Campaign of Hate Forces Azeri Journalist Offline, VOA (Jan. 8, 2021), https://www.voanews.com/press-freedom/campaign-hate-forces-azeri-journalist-offline.

[2] Id.

[3] Tom Tuite, Dubliner Charged with Harassing Journalists Remanded in Custody, The Irish Times (Jan. 18, 2021), https://www.irishtimes.com/news/crime-and-law/courts/district-court/dubliner-charged-with-harassing-journalists-remanded-in-custody-1.4461404.

[4] Brion Hoban & Sonya McLean, ‘Internet Troll’ Jailed for Sending Hundreds of Abusive Messages to Six Women, The Journal.ie (Nov. 14, 2019), https://www.thejournal.ie/brendan-doolin-court-case-4892196-Nov2019/.

[5] Lucy Westcott & James W. Foley, Why Newsrooms Need a Solution to End Online Harassment of Reporters, Comm. to Protect Journalists (Sept. 4, 2019), https://cpj.org/2019/09/newsrooms-solution-online-harassment-canada-usa/.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] See Anya Schiffrin, How to Protect Journalists from Online Harassment, Project Syndicate (July 1, 2020), https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/french-laws-tackle-online-abuse-of-journalists-by-anya-schiffrin-2020-07.

[9] Maeve Duggan, Online Harassment in 2017, Pew Rsch. Ctr. (July 11, 2017), https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/07/11/online-harassment-2017/.

[10] Id.

[11] Autumn Slaughter & Elana Newman, Journalists and Online Harassment, Dart Ctr. for Journalism & Trauma (Jan. 14, 2020), https://dartcenter.org/resources/journalists-and-online-harassment.

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Id.

[15] Id.

[16] Duggan, supra note 9.

[17] Law Libr. of Cong., Laws Protecting Journalists from Online Harassment 1 (2019), https://www.loc.gov/law/help/protecting-journalists/compsum.php.

[18] See id. at 3–4; Marlisse Silver Sweeney, What the Law Can (and Can’t) Do About Online Harassment, The Atl. (Nov. 12, 2014), https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2014/11/what-the-law-can-and-cant-do-about-online-harassment/382638/.

[19] Hollaback!, Online Harassment: A Comparative Policy Analysis for Hollaback! 37 (2016), https://www.ihollaback.org/app/uploads/2016/12/Online-Harassment-Comparative-Policy-Analysis-DLA-Piper-for-Hollaback.pdf.

[20] 18 U.S.C. § 2261A.

[21] § 2261A(2)(b).

[22] Hollaback!, supra note 19, at 38.

[23] Id.; see also 17 U.S.C. §§ 1201–1332.

[24] Hollaback!, supra note 19, at 38–39.

[25] Ala. Code § 13A-11-8.

[26] Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13-2916.

[27] Haw. Rev. Stat. § 711-1106.

[28] Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 6-2-506.

[29] Cal. Penal Code § 646.9.

[30] N.C. Gen. Stat. § 14-277.3A.

[31] Hollaback!, supra note 19, at 39 (providing more states that cover online harassment in their penal codes).

[32] State v. Shackelford, 825 S.E.2d 689, 701 (N.C. Ct. App. 2019), https://www.nccourts.gov/documents/appellate-court-opinions/state-v-shackelford. After meeting the victim once at a church service, the defendant promptly made four separate Google Plus posts in which he referenced the victim by name. Id. at 692. In one post, the defendant stated that “God chose [the victim]” to be his “soul mate,” and in a separate post wrote that he “freely chose [the victim] as his wife.” Id. After nearly a year of increasingly invasive posts in which he repeatedly referred to the victim as his wife, defendant was indicted by a grand jury on eight counts of felony stalking. Id. at 693–94.

[33] Law Libr. of Cong., supra note 17, at 1–2.

[34] Id. at 78–83.

[35] Id. at 83.

[36] Id.

[37] Id. at 78.

[38] Schiffrin, supra note 8.

Post Image by Kaur Kristjan on Unsplash.