14 Wake Forest L. Rev. Online 20

C. Isaac Hopkin

Introduction

This Note begins with the story of two investment managers. Manager One was an investment manager in Texas who oversaw funds exempt from registration with the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC” or the “Commission”).[1] Manager One set up two private investment partnership funds that held about $24 million in assets and had a little over a hundred investors.[2] These funds were described as “hedge-fund like” investments for sophisticated investors.[3] Following the 2008 crash, the funds failed.[4] In 2013, the SEC charged Manager One with fraud.[5] The SEC alleged that Manager One had (1) misrepresented who served as prime broker and as auditor; (2) misrepresented the funds’ investment parameters and safeguards; and (3) overvalued the funds’ assets to generate greater fees.[6] The SEC tried the case in an administrative forum.[7]

In 2014, the SEC administrative law judge (“ALJ”) found Manager One liable.[8] Later, the Commission granted an expedited five-year review before issuing its final order in September 2020.[9] The Commission imposed a monetary penalty of $300,000 on Manager One, ordered his fund to disgorge $685,000 in ill-gotten gains, and barred Manager One from securities activities.[10] Manager One repeatedly requested a jury trial in an Article III court and was repeatedly denied because the SEC, in its sole discretion, chose an administrative proceeding.[11]

Manager Two was also an investment manager in Texas who managed funds exempt from registration.[12] Manager Two set up multiple funds to pursue a hedge-fund-like strategy for sophisticated investors.[13] Following the 2001 crash, the funds collapsed due to a combination of mismanagement and market factors.[14] The SEC charged Manager Two with fraud for overvaluing his funds.[15] The SEC brought the action in federal district court, where the jury found Manager Two liable and imposed a civil penalty of $50,000, a permanent injunction, and a disgorgement of $900,000 of ill-gotten gains.[16]

Why were Manager One and Manager Two treated so differently? The difference is timing. When Manager One was charged, the SEC had to bring all civil enforcement actions against unregistered funds in an Article III court, where the jury right automatically attaches.[17] Unfortunately for Mr. Jarkesy (Manager One), he was charged in 2013 when the SEC had the discretion to choose between an Article III forum or an administrative forum to adjudicate its civil enforcement actions against unregistered funds.[18]

This dramatic shift in the SEC’s power was no accident. In response to the 2008 financial crash, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act, giving the SEC sole authority to pursue civil or equitable remedies in either an administrative forum or an Article III court.[19] Nothing limits the SEC’s discretion in this choice.[20] Moreover, the legislative history makes it clear that the SEC’s unbounded discretion was what Congress intended:

This section streamlines the SEC’s existing enforcement authorities by permitting the SEC to seek civil money penalties in cease-and-desist proceedings under Federal securities laws. The section provides appropriate due process protections by making the SEC’s authority in administrative penalty proceedings coextensive with its authority to seek penalties in Federal court. As is the case when a Federal district court imposes a civil penalty in a[n] SEC action, administrative civil money penalties would be subject to review by a Federal appeals court.[21]

As written, this provision puts the Seventh Amendment in the hands of the SEC. The Seventh Amendment protects civil jury trials “in suits at common law.”[22] The Supreme Court has held that when the government is litigating an action in an Article III court that is “analogous to suits at common law,” the Seventh Amendment attaches.[23] So how can the SEC can pursue the same remedies in a district court that requires a jury or in its own administrative courts that do not? The answer lies in the messy public rights exception, which allows the government to litigate in a non-Article III forum and where the Seventh Amendment “poses no independent bar” to non-jury factfinding.[24]

Despite the public rights exception, the SEC’s unfettered discretion is troubling.[25] As the statute stands now, the SEC could theoretically choose to grant one defendant’s Seventh Amendment rights while denying a similar defendant her Seventh Amendment rights.[26] This is the crux of the matter in Jarkesy.[27] When Jarkesy challenged the SEC, saying its discretion was unlawful under the Seventh Amendment, the Fifth Circuit agreed.[28] It found the SEC’s discretion unlawful suffered from two “constitutional defects.”[29] First, the court held that the SEC was not litigating a public right, and thus the Seventh Amendment required a jury trial.[30] Second, the Fifth Circuit held that Congress could not delegate forum choice to the SEC.[31] Both holdings reached the right result, but for the wrong reasons.

This Note analyzes the Fifth Circuit opinion in Jarkesy v. SEC by examining the interplay between administrative adjudication and the Seventh Amendment. Part I first explores the history of the Seventh Amendment and its importance at America’s founding. Next, Part I surveys the evolution of the public rights doctrine, specifically explaining how the public rights doctrine allows Article-III-like fact-finding outside Article III courts. This tension between the Seventh Amendment and public rights serves as the backdrop to the Fifth Circuit’s opinion.

Part II of this Note contends that the Fifth Circuit reached the correct outcome for the wrong reasons. The Fifth Circuit’s first holding was that the SEC’s cause of action was not a public right.[32] But this holding is likely wrong because the cause of action fits well into the Atlas Roofing[33] framework. Second, the Fifth Circuit held that the non-delegation doctrine prevented the SEC from choosing the forum.[34] This second holding defies relevant precedent surrounding the non-delegation doctrine.[35] Even so, the result of Jarkesy was correct. As this Note will explain, the opinion should have focused on how the SEC’s unique power over the forum fails to meet the exclusivity requirement found in Granfinanciera,[36] and thus was not a proper assignment. As a result, Mr. Jarkesy—along with others prosecuted under this statute—should have the right to elect a jury. Put differently, the defendants should control their Seventh Amendment rights, not the SEC. This framework provides an easy out for the Supreme Court, which recently granted certiorari in this case. Indeed, the Granfinanciera exclusive assignment requirement would allow the Court to preserve the administrative adjudication status quo while protecting Seventh Amendment rights. In that world, the Supreme Court could have its cake and eat it too.

I. Background, History, and a Battle of Fundamentals

The Seventh Amendment preserves an individual’s jury right in both common law and statutory civil actions.[37] Even so, when the government brings civil actions, the Seventh Amendment does not attach if the government is litigating a public right in a non-Article III forum.[38] This exception is called the public rights doctrine.[39] When a public right is involved, “the Seventh Amendment poses no independent bar”[40] to a non-Article III adjudication so long as “Congress properly assigns a matter to adjudication in a non-Article III tribunal.”[41] Whether a matter is properly assigned is a two-part inquiry: (1) whether the suit is analogous to one that existed at common law; and if so, (2) whether the government civil action is exempted by the public rights doctrine.[42] If either answer is no, defendants like Jarkesy do not have a Seventh Amendment right in the government’s civil action.

Cases like Jarkesy’s highlight two fundamental but conflicting goals in American law. On one side, the American commitment to a jury trial is as old as the country itself.[43] On the other, our Government prioritizes efficiency by using agencies and other bureaus to provide quick resolutions.[44] Thus, to understand Jarkesy, one must understand the history of the Seventh Amendment and the public rights exception.

A. Juries: The History, the Analysis, and the First Inquiry of Jarkesy

1. The Ancient Origin of Juries

“In Suits at common law . . . the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise re-examined in any court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.”[45] This is no small thing. Indeed, the Seventh Amendment was “paid for by thousands of years of slow progress and sacrifice of brave people who stood up for liberty.”[46] The concept of a jury dates back as far as ancient Greece,[47] but it did not evolve into the form contemplated by the Seventh Amendment until eighteenth-century England.[48]

In England, before trial by jury, two primary methods existed in judicial factfinding.[49] One method was trial by combat, where God would bring the truth to light.[50] God would do so during the trial by “giving force to the victor’s arms” while the two litigants fought on foot with a baton.[51] This method soon fell out of favor because trial by combat often lead to the death of noblemen whose life could be “otherwise employed.”[52]

The other, similarly dubious, method came in the form of sworn testimony.[53] With sworn testimony, the litigant presented a witness or witnesses, called compurgators, who swore to the litigant’s innocence or guilt.[54] This method was also problematic because many compurgators were chosen for their willingness to lie in exchange for payment.[55] The structure for factfinding in English law was a mixed bag ripe for reform.

The transformation of the English judicial process began with King Henry II.[56] He established professional judges and authorized “recognitors” or juries.[57] These juries resembled a modern grand jury.[58] The jury’s job was to “accuse” rather than to “try”

the cases.[59] Judge Pope, in his article, explained the process:

“Four persons from a vill, under oath, would report matters of public fame to twelve knights, also under oath. The knights were chosen from a larger area known as the hundred or the wapentake. If the twelve agreed, a presentment was made to the sheriff. After accusation came the trial.”[60]

Those indicted by the accusing jury could still be tried in front of a judge with the accusing jury serving as witnesses rather than triers of fact.[61]

Yet the problem of malicious prosecution remained. As a result, those accused of crimes could go before another jury to show that the charge was “procured out of hate and spite.”[62] If the jury found that the prosecution was false or malicious, the case was over.[63] Soon, the role of the second jury transformed from judging the jury to deciding the case itself.[64]

This process began as early as the thirteenth century.[65] The defendant could bring the same case to a second group “composed of men of a higher rank” called an “attainting jury.”[66] If the second jury disagreed with the first jury, the members of the first jury could be subject to imprisonment, forfeiture of lands, denial of credit, and sometimes death.[67] Out of the “attainting jury” system emerged our system of jurors who judge rather than accuse.[68] The attainting jury would consider what evidence was before the original jury and whether the prior jury accused properly on that evidence.[69] The attainting jury could only consider what was before the prior jury and could not draw any information outside the record.[70]

By the sixteenth century, however, the common law replaced this system, and judges gained the authority to grant a new trial rather than being subject to an attainting jury.[71] To do so, judges now had to hear the evidence along with the jury.[72] The jurors who brought the case had to disclose under oath anything they knew about the facts underlying the case.[73] Rather than jurors being the prosecutor and then the attainment jury determining facts, judges now could usurp the fact-finding function if they found the prosecuting jury’s evidence unsatisfactory.[74]

Perhaps poetically, the “critical moment” for the independent jury as we know it came in a trial against William Penn.[75] Penn, the twenty-six-year-old leader of the Quakers, was charged with “disturbing the King’s peace by preaching nonconformist religious views at an outdoor meeting in London.”[76] After hearing the case, four jurors “refused to convict Penn of the most serious charge.”[77] The judge sent the jury back to reach “the proper verdict,” but the jury again refused.[78] After reaching the wrong verdict again, the court sent the jurors back without “meat, drink, fire, or any other accommodation; they had not so much as a chamber-pot, though desired.”[79] Even in these dreadful conditions, the jurors again returned a verdict for Penn.[80] The court accepted the judgment, but the jurors were fined and jailed for contempt of court.[81] These jurors sued for habeas corpus.[82]

Lord Chief Justice Vaughn, in a monumental opinion, established that juries were entitled to reach their decisions independently.[83] Justice Vaughn observed:

[I]f the Judge having heard the evidence . . . shall tell the jury . . . the law is for the plaintiff, or for the defendant, and you are under the pain of fine and imprisonment to find accordingly, . . . every man sees that the jury is but a troublesome delay . . . and therefore the tryals by them may be better abolish’d than continued; which were a strange new-found conclusion, after a tryal so celebrated for many hundreds of years.[84]

This landmark opinion allowed jurors to be charged with facts, and the judge could no longer override those findings.[85]

Thus, by the eighteenth century, the English court system roughly resembled the forum we know it as today.[86] Judges presided over the trial, and jurors drawn from the community would judge the facts of the case.[87] Jurors were selected because they could determine the facts impartially and attorneys could challenge a juror for cause.[88] Witnesses were subject to open court and gave sworn testimony, and judges ruled on objections.[89] Then, jurors were allowed to privately deliberate until they reached their final verdict.[90] Thus, the common law system produced the modern jury system through the slow drag of time.

2. Juries and the Founding

The new independent jury system became “the grand bulwark of [English] liberties.”[91] Blackstone explained that trial by jury is the glory of the English law and “the most transcendent privilege which any subject can enjoy or wish for, that he cannot be affected, either in his property, his liberty, or his person, but by the unanimous consent of twelve of his neighbors and equals.”[92]

The right to a jury gained equal importance in Colonial America as “[it] was the germ of American freedom–the morning star of that liberty which subsequently revolutionized America.”[93] That is because the jury was one of the few protections against British overreach.[94] The colonists did not get to vote for Parliament, but they could make their grievances against the government known through the local jury.[95] The jury became a vehicle of resistance against British oppression, which in turn led to the British government avoiding jury trials.[96] For example, the Stamp Act cases were tried in admiralty courts in London, depriving many Americans of the local jury.[97] The British government’s manipulation of the system outraged the colonists to the point that the deprivation of their jury rights was a chief grievance in the Declaration of Independence.[98]

The jury protected the community from government overreach and served as a check on judges appointed by British officials.[99] In fact, civil juries were so important that the debate over the Bill of Rights was triggered by a casual comment by George Mason, in which he noted that “no provision was yet made for juries in civil cases.”[100] The Pennsylvania Anti-Federalists nearly prevented ratification of the Constitution because they believed the Federalists were attempting to abolish civil juries.[101] When the Federalists promised the Bill of Rights to assuage the Anti-Federalists concerns, seven of the states proposed amendments including the protection of the civil jury right.[102]

Yet, despite its apparent importance, little is known about the original purpose of the Seventh Amendment.[103] From the contextual history, a general guarantee of the civil jury was widely desired, but there was “no consensus on the precise extent of its power.”[104] For example, during the Constitutional Convention on September 15, 1787, a motion was made by General Thomas Pinckney and Elbridge Gerry to add the following to Article III: “And a trial by jury shall be preserved as usual in civil cases.”[105] Nathaniel Gorham responded to the motion, “The constitution of Juries is different in different States and trial itself is usual in different cases in different states.”[106] The motion was rejected and the convention ended without a guarantee of a civil jury trial.[107]

Even less is known about the debate surrounding the current language of the Seventh Amendment.[108] Madison originally proposed the language from the Virginia ratification convention, “In suits at common law, between man and man, the trial by jury, as one of the best securities to the rights of the people, ought to remain inviolate.”[109] The house committee then revised this language to say, “In suits at common law, the right of the trial by jury shall be preserved.”[110] The house passed the committee version without discussion.[111] The Senate then added, “where consideration exceeds twenty dollars.”[112] The record is sparse after that, but the Seventh Amendment was passed with little debate and ratified later on.[113] This Amendment—that inspired a revolution, that sparked the bill of rights, that was considered “the germ of American freedom–the morning star of that liberty”[114]—provides little light to those invoking it today.

3. Seventh Amendment Analysis

In cases like Jarkesy, Seventh Amendment history is an important prong that decides whether the trial can be held in an administrative forum or must be held in an Article III forum.[115] To determine whether a plaintiff is entitled to a jury, a court first evaluates whether the litigant has a Seventh Amendment right per Tull v. United States.[116]

To determine whether the Seventh Amendment applies, courts examine if the cause of action is “analogous to suits at common law” as existed at the time of the Seventh Amendment.[117] In Tull, the Court determined whether the Seventh Amendment applied against the government when it imposed a civil fine for violating the Clean Water Act.[118] The Supreme Court held that Tull was entitled to a jury trial because the action was analogous to the common law action of debt brought before juries in England.[119] In reaching its holding, the Court reasoned that common law extended not only to common-law actions—such as torts, contracts, or fraud—but also to claims created by congressional action.[120]

Following Tull, courts evaluate (1) the nature of the action and (2) the remedy sought.[121] If the nature of the statute and its remedy are analogous to actions and remedies that existed in eighteenth century England, then the Seventh Amendment attaches.[122] That said, in making this analysis, courts prioritize the nature of relief over the cause of action itself.[123] Thus, if the remedy is similar to one that at the time of the ratification of the Seventh Amendment would have been sought in a court of law rather than a court of equity, then the action is subject to a jury.[124]

4. Jarkesy’s Seventh Amendment Rights

Jarkesy is not William Penn, but his desire to pursue his right to an independent jury is understandable. It is even more understandable when a litigant sees the SEC’s astonishing win rate in administrative proceedings. According to the Wall Street Journal, the SEC won ninety percent of contested cases before an administrative law judge, compared to its sixty-nine percent success rate in federal court over the same time frame.[125]

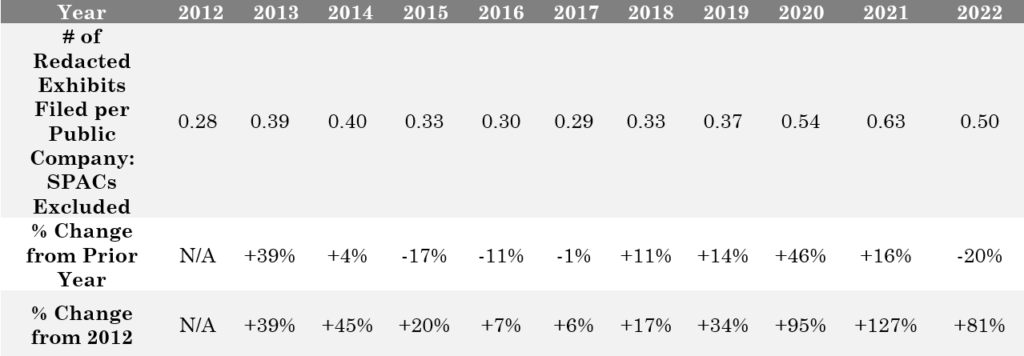

This disparity is especially relevant because the SEC uses the administrative forum much more often than Article III courts.[126] A litigant such as Jarkesy faces three potential SEC actions: (1) actions against brokers, (2) actions for reporting or accounting, or (3) actions against investment advisors. The SEC brought ninety percent of actions against brokers, eighty-four percent of actions for reporting or accounting, and seventy-four percent of actions against investment advisors in an administrative forum rather than an Article III court.[127] Anyone subject to the SEC’s enforcement could understandably feel like a litigant in Eighteenth century England where “every man sees that the jury is but a troublesome delay” rather than a “new-found conclusion, after a tryal so celebrated for hundreds of years.”[128]

B. The Public Rights Doctrine: History, Confusion, and the Second Inquiry of Jarkesy

In cases such as Jarkesy’s, the public rights doctrine is the greatest difference between an Article III forum, which carries a Seventh Amendment right, or an administrative proceeding, which is exempt from many Article III procedures. A public right is a government action related to an executive or legislative power.[129] In essence, public rights allow the government to litigate civil matters because it is enforcing them on behalf of the public. Consider securities laws. In response to the Great Depression and the stock market crash that precipitated it, Congress passed laws that allowed the government to initiate civil actions against bad actors.[130] Unlike every-day common law actions where the SEC initiates an enforcement action under securities law, the SEC is not validating the rights of a particular individual or itself, rather the SEC litigates on behalf of the public.[131] In those cases, the SEC is enforcing a public right. So long as a matter is a public right, Congress may properly assign it to a non-Article III forum, exempt from the Seventh Amendment.[132]

The public rights exception emerged before the twentieth century.[133] Yet since the founding, the executive and legislative branches have grown in both size—through new agencies—and scope—by said agencies enforcing civil penalties.[134] Accordingly, the public rights doctrine has had to adapt and change along with those branches to reflect the values that existed at the founding while also recognizing the new reality of a larger and broader federal government. Here, the Note explores the emergence of the public rights doctrine, the transformation into its modern form, and what makes a right public and thus exempt from jury trials.

1. Emergence of the Public Rights Doctrine

The public rights doctrine is supported by two different constitutional rationales: separation of powers and sovereign immunity.[135] Under the separation of powers theory, a public right may be tried in a non-Article III court because those causes of action are an exercise of executive or legislative powers, not judicial power.[136] The broad constitutional grants of power to the legislative and executive branches in Articles I and II of the Constitution necessitate some form of dispute resolution when that power is exercised.[137] When such dispute resolution is required, the public rights doctrine determines whether those branches can create their own fora, or whether such dispute resolutions are subject to the same restrictions constitutionally imposed on the judiciary.[138] Put another way, the public rights doctrine clarifies which actions stemming from Article I and II must be resolved by Article III courts and which actions are legislative or executive in their function and thus exempt from mandatory Article III court procedures.[139] As a result, the cause of action has no place in an Article III branch because the judiciary cannot exercise legislative nor executive power.[140]

The sovereign immunity rational for the public rights doctrine stems from the common law tradition. At common law, an individual was barred from suing the sovereign without its permission and the sovereign rarely (if ever) brought civil suits.[141] But the Article III language implicates many government actions: “All cases . . .[and] controversies to which the United States shall be a Party” are subject to Article III.[142] Thus public rights resolve the incongruence between when Article III applies to the sovereign, Thus, the public rights doctrine resolves the contradiction. If the cause of action is not a public right the sovereign would be subject to Article III litigation; when the cause of action is a public right the sovereign is shielded from Article III courts by the common law tradition of sovereign immunity.[143] Under this rationale, if Article III waives sovereign immunity, then Seventh Amendment protections attach.[144] Otherwise, the common law allows the government to form its own forum of dispute resolution, such as proceedings in front of an administrative law judge. Regardless of the underlying theory, the public rights exception allows the government to litigate on behalf of the public in a civil setting.

The first case to recognize the public rights doctrine was Murray’s Lessee v. Hoboken Land & Improvement Co. (Murray’s Lessee).[145] There, a dispute arose over property ownership where one party took lineal title while the other was a bona fide purchaser from the United States.[146] At issue was a statute that allowed the Treasury Department to issue a lien before it made findings in federal court.[147] The lineal title claimant challenged the statute, arguing that only Article III courts had the power to issue a lien and the Treasury-Department lien on his land was therefore invalid.[148]

The Court disagreed using the sovereign immunity rationale:

[T]here are matters, involving public rights, which may be presented in such form that the judicial power is capable of acting on them, and which are susceptible of judicial determination, but which Congress may or may not bring within the cognizance of the courts of the United States, as it may deem proper.[149]

Put differently, if the government is the owner of the land, it must consent to suit in an Article III court; otherwise, Congress may allow an executive department to grant relief.[150]

Public rights extended as the administrative state grew. In Crowell v. Benson,[151] a commissioner found Benson liable for injuries sustained by one of Benson’s employees as part of the Longshoremen’s and Harbor Workers’ Compensation Act.[152] The employee brought the action in an administrative forum as authorized by the statute, instead of the typical judicial forum, where the commissioner found him liable.[153] Benson challenged the act, arguing that the statute authorizing private suit violated inter alia “provisions of article 3 with respect to the judicial power of the United States.” [154]

The Supreme Court agreed using the public rights rationale. The Court explained that Congress may establish “legislative courts” for matters that “arise between the Government and persons subject to its authority in connection with the performance of the constitutional functions of the executive or legislative departments.”[155] But when matters arise between two private persons “to enforce constitutional rights[,]” Congress’s power to assign the matter is “an untenable assumption.”[156] Put another way, the separation of powers requires that the executive and legislative branches be exempt from Article III restrictions when using their powers because “functions of the executive or legislative departments” are not judicial powers. By comparison, when the matters relate to a judicial power, here maritime jurisdiction, such a matter cannot be assigned outside of Article III courts.

2. The Expansion of Public Rights to Reflect the Modern Administrative State

The drafters of the Seventh Amendment and Article III did not contemplate a world in which the government would try common law actions.[157] At the founding, litigation between citizens and the State was rare outside of criminal matters.[158] In the civil context, government actions brought in common law courts were mostly contractual disputes.[159] Thus, the language of the Seventh Amendment and Article III do not contemplate actions like Jarkesy where the government brings an action analogous to a common law fraud claim.[160]

The Court addressed the increasing divergence between historic practices and the modern government in Atlas Roofing Co. v. Occupational Safety & Health Review Commission.[161] In Atlas Roofing, the company challenged the administrative proceeding against it, arguing that conducting the action in an administrative forum deprived the company of its Seventh Amendment right because the proceeding involved a common-law claim.[162] The Court rejected this argument, explaining that OSHA had litigated a public right and therefore did not require a jury trial.[163] The Court held that when Congress creates a new statutory public right, Congress may assign the adjudication of that right to an administrative agency.[164] “The distinction is between cases of private right and those which arise between the government and persons subject to its authority in connection with the performance of the constitutional functions of the executive or legislative function.”[165] The Court’s holding consolidated both the separation of powers and sovereign immunity rationales by requiring the government to be a named party and Congress to create “a new cause of action unknown to the common law” for the public right doctrine to apply.

But in later holdings, the Court held that the first condition of Atlas Roofing, which required that the government be a party to the suit, was no longer necessary for a right to be deemed a public right. In Thomas v. Union Carbide Agricultural Products Co.,[166] the Court examined “whether Article III of the Constitution prohibit[ed] Congress from selecting binding arbitration . . . as the mechanism for resolving disputes among participates in FIFRA’s pesticide registration scheme.”[167] The Court found that it did not because the matter was a public right and thus exempt from Article III.[168] The majority explained that Congress may choose “quasi-judicial methods of resolving matters” when those matters concern “an integral part of a [Congressional] program.”[169] Put differently, the focus is on substance rather than form.[170] This case returned the Court to the separation of powers rationale where a matter became a public right when it was an exercise of Congressional power.[171] Thus, as the doctrine stands today, a matter becomes a public right when it concerns an exercise of legislative or executive power; when the matter becomes a public right, the matter can be assigned to a non-Article III forum.

In sum, the distinction between a public right and a private right is whether the right is “integrally related to a particular federal government action.”[172] If it relates to an executive or legislative function, then the right is public.[173] If a party is litigating a public right, then the Seventh Amendment “poses no independent bar to the adjudication of that action by a nonjury factfinder.”[174] Simple, right?

Yet scholars and courts agree that determining what a public right is creates a procedural and judicial mess.[175] This mess is apparent in Jarkesy.[176] On one hand, the action involves the government acting in its sovereign capacity to enforce securities law.[177] On the other hand, this action is eerily similar to the action in Tull where an administrative agency was enforcing a civil penalty based on a common law cause of action.[178] This tension is at the heart of both the public rights doctrine and Jarkesy itself.

3. Separation of Powers Analysis and Jarkesy

Typically, administrative adjudication does not trigger the Seventh Amendment because it enforces public rights assigned to non-Article III forums.[179] Accordingly, when Congress properly assigns such a matter to an agency, then no jury right attaches.[180] Congress may properly assign the matter when no Article III powers are implicated.[181] Agency adjudications do not exercise Article III powers and are thus properly assigned in three instances:

(1) those where there is no deprivation of life, liberty, or property; (2) those deprivations that nonetheless satisfy due process such as in Murray’s Lessee; and (3) those where the agency exercises no power at all, because it serves as a judicial adjunct.[182]

Under the first type of case where there is not a deprivation, non-Article III adjudication is permissible because there is no due process concern. For example, when the government issues a benefit and then revokes that benefit, such an action would not—absent unusual circumstances—be subject to a to an Article III court because there is no deprivation involved.[183] The Fifth Circuit found that this type of exemption is not the type in Jarkesy’s suit because he was subject to a civil penalty—i.e., a deprivation of property.[184]

The second framework is permitted even in cases of deprivation where due process and fair procedures are present.[185] For example, in Murray’s Lessee, the litigant was only subject to a temporary lien that he could later contest in court.[186] Congress could properly allow the executive to issue a lien because it was temporary “until a decision should be made by the court.”[187] Consequently, any deprivation in life, liberty, and property without adjudication in the courts was minimal. By contrast, Jarkesy is not concerned with mere temporary deprivation. In fact, Jarkesy was barred from his chosen profession of securities trading for years until the final adjudication took place.[188] The deprivation, while potentially subject to review, has been far too punitive for far too long to qualify for the Murray’s Lessee exception.

The third category—the one that likely fits best in Jarkesy—allows non-Article III adjudication when the agency is not responsible for the exercise of judicial or executive powers.[189] For example, in Crowell, administrative agencies could participate in factfinding because the source of the power was “determin[ing] various matters arising between the government and others, which from their nature do not require judicial determination.”[190] When the government is bringing a case analogous to common law fraud, this power has been called a “replacement right.”[191] A “replacement right” refers to when Congress substitutes an existing common law remedy with an administrative one and assigns the right’s adjudication to a non-Article III forum.[192]

This description best fits with Jarkesy because the SEC’s action against him was subject to Article III authority until the Dodd-Frank Act.[193] Following the Dodd-Frank Act, the SEC now has the power to exercise its replacement right selectively,[194] so the jury right attaches only when the SEC chooses to bring the action in an Article III court.[195] Therefore, like in Crowell, it is a public right because the SEC is vindicating the public interest.

Yet replacement rights create separation of powers issues because Congress is supplanting existing judicial authority.[196] Indeed, to do so, the legislation must be an exercise of legislative or executive power. This is especially unique in a case such as Jarkesy, in which the SEC sometimes chooses to bring the case within Article III powers and other times exercises its own adjudication powers. This is where the heart of the matter lies in Jarkesy—what power is the SEC exercising when trying the suit in its own forum?

II. How the Supreme Court Can Have Its Cake and Eat It Too: The Fifth Circuit Was Right in Jarkesy but for the Wrong Reasons

Jarkesy’s reasoning “cuts against [] Supreme Court precedent on the applicability of the Seventh Amendment to agency proceedings involving ‘public rights.’”[197] The question presented to the panel was whether Jarkesy had the right to a jury trial in the SEC’s proceeding against him.[198] The Fifth Circuit held that Jarkesy was entitled to a jury because the SEC was not litigating a public right, or, alternatively, Congress had violated the non-delegation doctrine by allowing the SEC to choose its forum.[199]

The opinion focused on whether the statutory cause of action was a public right.[200]This inquiry assessed “whether Congress may assign” the matter to a non-Article III forum.[201] As explained below, [202] Congress could assign it to the SEC because it likely was a public right. Instead, the panel should have focused on the other aspect of Granfinanciera which asks “whether Congress . . . has assigned resolution of the relevant claim to a non-Article III adjudicative body.”[203]

Despite the cause of action implicating a public right, Congress did not properly assign it to the SEC. Under Granfinanciera, “[u]nless Congress may and has permissibly withdrawn jurisdiction over that action by courts of law and assigned it exclusively to non-Article III tribunals sitting without juries, the Seventh Amendment guarantees petitioners a jury trial upon request.”[204] By allowing the SEC discretion to pick a forum with or without a jury, Congress has not satisfied Granfinanciera because it has not exclusively assigned the action to a non-article III tribunal. Consequently, without proper assignment, the action is subject to Article III protections.[205]

This sets up a simple solution for the Supreme Court. At minimum, a defendant should have the same right to invoke Article III as the SEC. Granfinanciera provides the way. By finding that Jarkesy is entitled to a jury because the action was not “exclusively assigned,” the Court can allow Jarkesy his Seventh Amendment rights without undermining the entirety of administrative adjudication. Rather, administrative adjudication would maintain its status quo because Atlas Roofing and Granfinanciera remain unchanged. By this narrow ruling, the Court can have its cake, maintaining a complex administrative structure, and eat it too, strengthening Seventh Amendment rights.

A. The Jarkesy Framework

In this Subpart, the Note explains what the Fifth Circuit’s relevant holdings were and why they were not right in light of Granfinanciera, Atlas Roofing, etc. This Subpart is split into the two major portions of the opinion: first the public rights framework and second the non-delegation framework. These portions of the opinion were alternative holdings about Jarkesy’s right to a jury trial.

1. Public Rights Framework: Part I of the Opinion

The first holding in the Fifth Circuit Opinion was that the SEC was not litigating a public right and thus Jarkesy was entitled to a jury.[206] Courts answer two questions to determine whether an administrative litigant is entitled to a jury: first whether the cause of action existed at common law under the Seventh Amendment, and second whether the cause of action is a public right.[207] In this case, it is not disputed that the first inquiry is met. The SEC’s civil penalty is just like the civil penalty evaluated in Tull––an action at debt.[208] For the second inquiry, determination of whether public rights are implicated, the court considers: (1) whether “Congress ‘creat[ed] a new cause of action, and remedies therefor[e], unknown to the common law,’ because traditional rights and remedies were inadequate to cope with a manifest public problem;” and (2) whether jury trials would “go far to impede swift resolution of the matter.”[209]

The Fifth Circuit’s analysis under the first prong is questionable given current caselaw. The panel held that the SEC was not litigating a public right because the action was analogous to common law fraud.[210] But this contradicts Atlas Roofing, which found that a tort like action without damages is “unknown to the common law.”[211] To distinguish Atlas Roofing, the majority explained that “OSHA empowered the government to pursue civil penalties and abatement orders whether or not any employees were ‘actually injured’ . . . .”[212] The court continued, “The government’s right to relief was exclusively a creature of statute and therefore was distinctly public in nature.”[213] The majority then analogized the SEC’s cause of action to common law fraud.[214]

This point is puzzling because the panel proves the SEC’s point. The SEC argued that its fraud claims are unique because the agency need not demonstrate loss.[215] In fact, just like in Atlas Roofing, the SEC’s analogous action lacks the damages component.[216] Proving actual damages is vital to common law fraud.[217] Here, the statute Congress passed creates a new action different from the common law because, even though it mirrors the most of the elements of common law fraud, the SEC need not demonstrate damages.[218] In this way, the statute is nearly identical to the statute at issue in Atlas Roofing, which also mirrored a common-law claim lacking damages. Thus, the Fifth Circuit’s attempt to differentiate Atlas Roofing fails because the panel’s focus was misplaced. What makes an action “unknown to the common law” is not a lack of similar elements, here misrepresentation.[219] Similarity is inevitable. Rather, an action is “unknown to the common law” when it lacks one of the common elements, here damages.[220]

The panel also tried to reason that Atlas Roofing was unique because it asked “factfinders to undertake detailed assessments of workplace safety condition and to make unsafe-conditions findings even if no injury occurred.”[221] But again on this point, the SEC’s power is similar in that it investigates securities fraud actions, makes findings on whether fraud occurs, and brings actions even if no damages have occurred.[222] For this reason, analogy to common law is not enough to overcome the public rights exception outlined in Atlas Roofing because fraud without damages is “unknown to the common law.”[223]

For the other element of the Atlas Roofing test, whether jury trials go far to “impede swift resolution” of the action, the Fifth Circuit’s reasoning has more support.[224] To begin with, the current litigation took seven years.[225] Seven years is not considered a swift resolution, even in judicial-time.[226] And the SEC still brings similar actions in district court which cuts against the argument that jury trials impede swift resolution.[227] Requiring an Article III trial would not “impede swift resolution” because even the SEC agrees that Article III courts can handle these claims.[228]

In sum, the opinion ignored the comparison between the cause of action in Atlas Roofing by OSHA and the cause of action brought by the SEC. Consequently, under current case law, it is likely that the action brought by the SEC is a public right and thus exempt from the Seventh Amendment requirements.

2. The Non-Delegation Non-Starter: Part II of the Opinion

The Jarkesy court was “almost certainly wrong” in the non-delegation part of its opinion.[229] In that portion, the panel held that even if the Commission’s cause of action were enforcing a public right, Congress improperly delegated a legislative power to the SEC.[230]

The majority observed that the language of Article I provides that all legislative powers must be vested in the Congress.[231] The Court also reasoned that forum selection is a legislative power.[232] It is a legislative power because “assigning disputes to agency adjudication”[233] “alter[s] the legal rights of, duties, and relations of persons . . . outside the legislative branch.”[234] In addition, “the mode of determining which cases are assigned to administrative tribunals ‘is completely within congressional control.’”[235] Thus, because forum selection is a legislative power, Congress must articulate “an intelligible principle” to control the exercise of that power if delegating it to an agency.[236] The Jarkesy court reasoned that Congress did not give an intelligible principle when delegating forum selection to the SEC and it was thus an unconstitutional delegation.[237]

The non-delegation requirement has only been applied “when Congress has delegated power directly to the President—never when Congress has delegated power to agency officials.”[238] Although some Justices have signaled this may change, that reception has only been in dissents and concurrences.[239] In fact, the Fifth Circuit rejected Congress’s delegation to an administrative agency by citing those dissents instead of any majority opinions.[240] In essence, the Jarkesy court tenuously relied on the expansion of an already disputed doctrine.

The court was, in my opinion, correctly wary of the SEC’s complete discretion over forum. But its holding misconstrued existing case law and relied on non-delegation, which has not applied to this sort of action before. Alternatively, the Fifth Circuit could have held that Congress did not exclusively assign the action to the SEC, allowing Jarkesy to invoke an Article III forum. This is directly supported by the case law, particularly Granfinanciera.

B. Did Congress Assign the Action? The Exclusivity Principle: A Way Out for the Court?

This Note agrees with the Fifth Circuit: the SEC should not have complete discretion over forum. Congress should choose the forum and the SEC must follow. Yet, the Fifth Circuit’s holding ventured far beyond the caselaw to reach this result. Rather than base its holding on broad (and novel) interpretations of the caselaw, the Fifth Circuit instead should have issued a narrow opinion based on Granfinanciera. In doing so, the court could have reached the same result—a jury right for Jarkesy—without relying on a Supreme Court dissenting opinion for its rule.[241]

Granfinanciera answers when the Seventh Amendment prevents non-Article III adjudication.[242] The test is whether Congress “may and has assigned resolution of the relevant claim to a non-Article III adjudicative body that does not use a jury as a factfinder.”[243] Congress may assign any action that is a public right.[244] Under Granfinanciera, it is likely that the SEC was litigating a public right against Jarkesy because the action is unknown to the common law.[245] Thus, Congress may assign it. The question then is whether Congress has assigned it. Under Granfinanciera, the answer is no.

Congress has not assigned a public right unless adjudication of that right is given “exclusively to non-article III tribunals sitting without juries.”[246] Otherwise, “the Seventh Amendment guarantees petitioners a jury trial upon request.”[247] Thus, to assign means to exclusively assign. Without exclusive assignment, the Seventh Amendment requires a jury trial upon a defendant’s request.[248]

The requirement for exclusive assignment is found in many of the Court’s public rights precedents. In Atlas Roofing the Court stated, “Congress has often created new statutory obligations, provided for civil penalties for their violation and committed exclusively to an administrative agency the function of deciding whether a violation has in fact occurred.”[249] In Ex parte Bakelite Corp.,[250] the Court stated, “Congress may reserve to itself the power to decide, may delegate that power to executive officers, or may commit it to judicial tribunals.”[251] The Court stated in Thomas that “the public rights doctrine reflects simply a pragmatic understanding that when Congress selects a quasi-judicial method of resolving matters that ‘could be conclusively determined by the Executive and Legislative Branches,’ the danger of encroaching on the judicial powers is less than when private rights.”[252] In sum, exclusivity ensures actual assignment, which in turn secures the rights of the parties before litigation ever starts.

Here, unlike other public rights cases, the relevant statute did not exclusively assign the matter outside of Article III courts. In fact, the statute gives the SEC complete autonomy to litigate in an Article II forum, its own administrative court, or an Article III forum.[253] The SEC’s autonomy violates the exclusivity requirement found in Granfinanciera and other public rights cases. Whether the Seventh Amendment applies “turns not solely on the nature of the issue to be resolved, but also the forum in which it is resolved.”[254] In Jarkesy, the SEC chooses the forum and thus had complete control over Jarkesy’s Seventh Amendment right. Granfinanciera does not tolerate this level of agency autonomy. Indeed, by requiring exclusive assignment, a court ensures that control over the Seventh Amendment is not left to an agency’s whims. Instead, Congress may both create a new right and define the parameters of that right.

Thus, the Fifth Circuit improperly based its opinion on non-delegation rather than proper assignment. When the matter is not exclusively assigned, the Seventh Amendment steps in and assures the litigant has a jury right if they so elect. This holding would have resulted in the same outcome, a jury trial for Jarkesy, without going against Atlas Roofing’s precedent, or alternatively relying on a theoretical doctrine not adopted in any controlling precedent.

C. Proposal

The exclusivity requirement opens an easy path for the Supreme Court to follow. One of the concerns consistently expressed by the Justices is how finding for Jarkesy could upend agency adjudication.[255] Yet another consistent concern is how easily Congress could deprive anyone of a jury right if they wanted to.[256]

In responding to these concerns, Granfinanciera gives the Supreme Court a chance to have its cake and eat it too. Rather than upending practically all administrative adjudications or further weakening the Seventh Amendment, exclusive assignment allows the Justices to take a small step in preserving both. The Supreme Court could reject the Fifth Circuit’s opinion under Atlas Roofing and still hold that Granfinanciera requires exclusive assignment. Under that rule, Jarkesy and anyone else similarly prosecuted may elect for a jury trial or consent to an SEC trial because Granfinanciera requires it.[257] Thus, the Supreme Court can have its cake and eat it too.

Alternatively, the SEC could moot this issue today by giving litigants the option to choose Article II or Article III forum.[258] The SEC can accomplish this without Congress, as it will simply be an administrative procedure which is exempt from notice and comment rulemaking.[259] By selecting a forum through notice and comment procedures, the SEC would protect its interest in efficiency while preserving a litigant’s Seventh Amendment rights. Either way, the resolution need not upend all agency adjudication. Rather, any solution could be tailored to preserve SEC efficiency and the Seventh Amendment rights.

Conclusion

In sum, juries are an ancient and an important right, though not an untouchable one. Juries may be abrogated when the action is not one “at common law” or when the right being litigated is a public right. Public rights are those rights which are closely intertwined with an executive or legislative scheme. Even so, just because an action may be a public right in theory, it still must be assigned to be litigated in a non-Article III forum. Without exclusive assignment to a non-jury forum, the Seventh Amendment attaches. In Jarkesy, the SEC brought a case in an administrative forum for civil penalties. The majority opinion held that this was unconstitutional because the SEC was not litigating a public right. Even still, this action reflects other actions brought by administrative agencies. It sounds in common law but is a new action because it lacks one of the vital elements of common-law claims, damages. But unlike other public rights, the SEC has the power to bring the action in one forum with a jury right and one without a jury right. This violates the exclusivity principle as explained in Granfinanciera. Exclusivity provides an easy way out for the Court and even the SEC itself. So long as the SEC has this right, the defendant ought to maintain it too. By doing so, the Court, the SEC, and other parties may protect the legislative scheme, the administrative state, and also the Seventh Amendment.

C. Isaac Hopkin[260]*

-

. Brief of Phillip Goldstein et al. as Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners, Jarkesy v. SEC, 34 F.4th 446 (5th Cir. 2022) (No. 20-61007), 2021 WL 1856946, at *6 [hereinafter Cuban Brief]; Brief of the New Civil Liberties Alliance as Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioners, Jarkesy, 34 F.4th 446 (No. 20-61007), 2021 WL 1856951, at *3 [hereinafter NCLU Brief]. ↑

-

. Jarkesy v. SEC, 34 F.4th 446, 450 (5th Cir. 2022), cert. granted, 143 S. Ct. 2688 (2023). ↑

-

. Brief for the Cato Institute as Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioners, Jarkesy, 34 F.4th 446 (5th Cir. 2022) (No. 20-61007), 2021 WL 1149884, at *2 [hereinafter Cato Brief]. ↑

-

. NCLU Brief, supra note 1, at *3. ↑

-

. Jarkesy, 34 F.4th at 450. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. at 449. ↑

-

. NCLU Brief, supra note 1, at *3. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Jarkesy, 34 F.4th at 450. ↑

-

. See, e.g., Jarkesy v. SEC, 803 F.3d 9, 30 (D.C. Cir. 2015) (denying Manager 1 his jury request because the court lacked subject-matter jurisdiction for the case). ↑

-

. SEC v. Seghers, 298 F.App’x 319, 323 n.2 (5th Cir. 2008). ↑

-

. Id. at 322. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. at 323. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Thomas Glassman, Ice Skating up Hill: Constitutional Challenges to SEC Administrative Proceedings, 16 J. Bus. & Sec. L. 47, 68 (2015). ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. 15 U.S.C. § 78u(d) (authorizing the SEC to seek monetary penalties); id. § 78u-3 (authorizing the SEC to choose the forum). ↑

-

. Jarkesy v. SEC, 34 F.4th 446, 450 (5th Cir. 2022), cert. granted, 143 S. Ct. 2688 (2023). ↑

-

. H.R. Rep. No. 111-687, pt. 1, at 78 (2010). ↑

-

. U.S. Const. amend. VII. ↑

-

. Tull v. United States, 481 U.S. 412, 417 (1987). ↑

-

. Granfinanciera, S.A. v. Nordberg, 492 U.S. 33, 53 (1989). ↑

-

. See NCLU Brief, supra note 1, at *14; Jarkesy, 34 F.4th at 462. ↑

-

. See Cuban Brief, supra note 1, at *6. ↑

-

. 34 F.4th 446 (5th Cir. 2022), cert. granted, 143 S. Ct. 2688 (2023). ↑

-

. Id. at 459, 462. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. at 457. ↑

-

. Id. at 462–63. ↑

-

. Id. at 451–60. ↑

-

. 430 U.S. 442 (1977). ↑

-

. Tull v. United States, 481 U.S. 412, 425 (1987). ↑

-

. See infra pp. 34–35. ↑

-

. Granfinanciera, S.A. v. Nordberg, 492 U.S. 33, 49 (1989). ↑

-

. Tull, 481 U.S. at 417. ↑

-

. See William Baude, Adjudication Outside Article III, 133 Harv. L. Rev. 1511, 1570–71 (2020). ↑

-

. Thomas v. Union Carbide Agric. Prods. Co., 473 U.S. 568, 589 (1985). ↑

-

. Granfinanciera, 492 U.S. at 53–54. ↑

-

. Oil States Energy Servs., LLC v. Green’s Energy Grp., LLC, 138 S. Ct. 1365, 1379 (2018) (quoting Granfinanciera, 492 U.S. at 53–54). ↑

-

. Jarkesy v. SEC, 34 F.4th 446, 453 (5th Cir. 2022), cert. granted, 143 S. Ct. 2688 (2023). ↑

-

. See The Declaration of Independence para. 20 (U.S. 1776) (“He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: . . . For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury.”). ↑

-

. See Paul R. Verkuil, The Emerging Concept of Administrative Procedure, 78 Colum. L. Rev. 258, 279 (1978) (“It is equally important . . . to provide mechanisms that will not delay or frustrate substantive regulatory programs.”). Efficiency is the one of the SEC’s justifications for use of the administrative forum over district courts. “From the standpoint of deterrence and investor protection, I think we can all agree that it is better to have rulings earlier than later.” Andrew Ceresney, Director, SEC Div. of Enforcement, Remarks to the American Bar Association’s Business Law Section Fall Meeting (Nov. 21, 2014) (transcript available at http://perma.cc/C9HU-FB9V). ↑

-

. U.S Const. amend. VII. ↑

-

. Jennifer Walker Elrod, Is the Jury Still Out?: A Case for the Continued Viability of the American Jury, 44 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 303, 310 (2012). Judge Jennifer Walker Elrod was the Judge who authored the Jarkesy opinion. Jarkesy v. SEC, 34 F.4th 446 (5th Cir. 2022), cert. granted, 143 S. Ct. 2688 (2023). ↑

-

. Elrod, supra note 46, at 310. ↑

-

. Id. at 314. ↑

-

. See id. at 311. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Edward L. Rubin, Trial by Battle. Trial by Argument., 56 Ark. L. Rev. 261, 263 (2003). ↑

-

. Elrod, supra note 46, at 268–69. ↑

-

. See id. at 311. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Jack Pope, The Jury, 39 Tex. L. Rev. 426, 431 (1961). The reform process was not for some noble purpose, instead it was to keep revenue in the King’s Court rather than going to local tribunals. See id. ↑

-

. Id. at 432. ↑

-

. See id. at 431–39. ↑

-

. Id. at 434. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. at 435. ↑

-

. Pope, supra note 56, at 434. ↑

-

. Id. at 434–35. ↑

-

. Id. at 435. ↑

-

. Id. at 441. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Elrod, supra note 46, at 313. ↑

-

. Pope, supra note 56, at 441–42. ↑

-

. Id. at 442. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. at 442–43. ↑

-

. Pope, supra note 56, at 445. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Elrod, supra note 46, at 313. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. (quoting 6 Cobbett’s Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason and Other Crimes and Misdemeanors from the Earliest Period to the Present Time 964 (1810)). ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Elrod, supra note 46, at 313. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. at 313–14. ↑

-

. Bushell’s Case, 124 Eng. Rep. 1006, 1010 (C.P. 1670). ↑

-

. Pope, supra note 56, at 443. ↑

-

. See id. at 444 ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. 4 William Blackstone, Commentaries *342. ↑

-

. Id. at *379. ↑

-

. Elrod, supra note 46, at 314–15. ↑

-

. Id. at 315. ↑

-

. Akhil Reed Amar, A Tale of Three Wars: Tinker in Constitutional Context¸ 48 Drake L. Rev. 507, 514 (2000). ↑

-

. Rachel E. Barkow, Recharging the Jury: The Criminal Jury’s Constitutional Role in an Era of Mandatory Sentencing, 152 U. Pa. L. Rev. 33, 52–53 (2003). ↑

-

. Id. at 53. ↑

-

. The Declaration of Independence para. 20 (U.S. 1776) (“He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: . . . For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury.”). ↑

-

. Akhil Reed Amar, The Bill of Rights as a Constitution, 100 Yale L.J. 1131, 1183 (1991). ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Kenneth S. Klein, The Validity of the Public Rights Doctrine in Light of the Historical Rationale of the Seventh Amendment, 21 Hastings Const. L.Q. 1013, 1018 (1994). ↑

-

. Id. at 1019. ↑

-

. Edith Build Henderson, The Background of the Seventh Amendment, 80 Harv. L. Rev. 289, 291–92 (1966). ↑

-

. Id. at 299. ↑

-

. Id. at 293–94. ↑

-

. Id. at 294. ↑

-

. Id. at 294–95. ↑

-

. See Charles W. Wolfram, The Constitutional History of the Seventh Amendment, 57 Minn. L. Rev. 639, 730 (1973). ↑

-

. Id. at 728. ↑

-

. Id. at 729. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. at 730. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Julius J. Marke, Peter Zenger’s Trial, 6 Litig. 41, 55 (1980). ↑

-

. Atlas Roofing Co. v. Occupational Safety & Health Rev. Comm’n, 430 U.S. 442, 460–61 (1977). ↑

-

. 481 U.S. 412 (1987). ↑

-

. Id. at 417 (internal quotation omitted). ↑

-

. Id. at 414. ↑

-

. Id. at 418. ↑

-

. Id. at 417 (citing Curtis v. Loether, 415 U.S. 189, 193 (1974)). ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Tull v. United States, 481 U.S. 412, 417 (1987). ↑

-

. Id. at 420. ↑

-

. Id. at 423. ↑

-

. Jean Eaglesham, SEC Wins with In-House Judges, Wall St. J. (May 6, 2015, 10:30 PM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/sec-wins-with-in-house-judges-1430965803. ↑

-

. See SEC, Addendum to Division of Enforcement Press Release Fiscal Year 2022 (2022), https://www.sec.gov/files/fy22-enforcement-statistics.pdf. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Bushell’s Case, 124 Eng. Rep. 1006, 1010 (C.P. 1670). ↑

-

. Stern v. Marshall, 564 U.S. 462, 490–91 (2011). ↑

-

. See Glassman, supra note 17, at 50. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Oil States Energy Servs., LLC v. Green’s Energy Grp., LLC, 138 S. Ct. 1365, 1379 (2018). ↑

-

. See Den v. Hoboken Land & Improvement Co. (Murray’s Lessee), 59 U.S. (18 How.) 272, 284 (1855). ↑

-

. See Ellen E. Sward, Legislative Courts, Article III, and the Seventh Amendment, 77 N.C. L. Rev. 1037, 1064, 1103 (1999). ↑

-

. Klein, supra note 101, at 1023. ↑

-

. Baude, supra note 38, at 1577. ↑

-

. Klein, supra note 101, at 1023–24. ↑

-

. Id. at 1024–25. ↑

-

. Id. at 1024. ↑

-

. See id.; see also Oceanic Steam Navigation Co. v. Stranahan, 214 U.S. 320, 339 (1909) (Congress could “impose appropriate obligations and sanctions their enforcement by reasonable money penalties, giving executive officers the power to enforce such penalties without the necessity of invoking judicial power.”). ↑

-

. See Sward, supra note 134, at 1064. ↑

-

. Klein, supra note 101, at 1024. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. at 1024, 1031–32. ↑

-

. 59 U.S. (18 How.) 272 (1855). ↑

-

. Id. at 284–85. ↑

-

. Id. at 274. ↑

-

. Id. at 275. ↑

-

. Id. at 284. ↑

-

. Klein, supra note 101, at 1025. ↑

-

. 285 U.S. 22 (1932). ↑

-

. Id. at 36–37. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. at 37. ↑

-

. Id. at 50. ↑

-

. Id. at 60–61. ↑

-

. See Sward, supra note 134, at 1064, 1103. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. See Jarkesy v. SEC, 34 F.4th 446, 454 (5th Cir. 2022), cert. granted, 143 S. Ct. 2688 (2023) (describing the SEC’s action as akin to common law fraud). ↑

-

. 430 U.S. 442 (1977). ↑

-

. Id. at 448–49. ↑

-

. Id. at 460. ↑

-

. Id. at 455. ↑

-

. Id. at 452 (quoting Crowell v. Benson, 285 U.S. 22, 50–51 (1932)). ↑

-

. 473 U.S. 586 (1985). ↑

-

. Id. at 571. FIFRA’s pesticide registration scheme is a matter for another law review article. For a summation of its process, see id. at 572–75 and Ruckelshaus v. Monsanto Co., 467 U.S. 986, 991–97 (1984). ↑

-

. Thomas, 473 U.S. at 593–94. ↑

-

. Id. at 589. ↑

-

. Id. at 587. ↑

-

. See id. at 589–93. ↑

-

. Stern v. Marshall, 564 U.S. 462, 490–91 (2011). ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Granfinanciera, S.A. v. Nordberg, 492 U.S. 33, 53 (1989) (citing Atlas Roofing Co. v. Occupational Safety & Health Rev. Comm’n, 430 U.S. 442, 453–55 (1977)). ↑

-

. Baude, supra note 38, at 1520, 1542, 1547; Robert L. Glicksman & Richard E. Levy, The New Separation of Powers Formalism and Administrative Adjudication, 90 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 1088, 1138 (2022) (“[T]he current doctrine concerning administrative adjudication is confusing and poorly defined.”). Efforts by judges to define public rights is equally confused. See Stern v. Marshall, 564 U.S. 462, 488 (2011) ([O]ur discussion of the public rights exception since that time has not been entirely consistent . . . .”); see also Transcript of Oral Argument at 6, SEC v. Jarkesy, 143 S. Ct. 2688 (2023) (No. 22-859) (“The court has never fully plumbed its outer perimeters.”). ↑

-

. 34 F.4th 446 (5th Cir. 2022), cert. granted, 143 S. Ct. 2688 (2023). ↑

-

. Id. at 467 (Davis, J. dissenting). ↑

-

. Id. at 454 (majority opinion) (citing Tull v. United States, 481 U.S. 412, 481 (1987)). ↑

-

. William F. Funk, Sidney A. Shapiro, & Russell L. Weaver, Administrative Procedure and Practice 558 (6th ed. 2019). ↑

-

. Oil States Energy Servs., LLC v. Green’s Energy Grp., LLC, 138 S. Ct. 1365, 1379 (2018) (emphasis added) (quoting Granfinanciera, S.A. v. Nordberg, 492 U.S. 33, 53–54 (1989)). ↑

-

. Baude, supra note 38, at 1577. ↑

-

. Id. Of course, this is not a perfect diagram that explains all the Court’s relevant holdings. Some cases are public rights because they embody a little bit of each category. See id. at 1578. ↑

-

. See, e.g., Matthews v. Eldridge, 424 U.S. 319 (1976) (rejecting court-like procedures in an administrative forum, because the plaintiff had adequate notice). ↑

-

. Jarkesy v. SEC, 34 F.4th 446, 453 (5th Cir. 2022), cert. granted, 143 S. Ct. 2688 (2023). ↑

-

. Baude, supra note 38, at 1578. ↑

-

. Id. at 1552–53. ↑

-

. Murray’s Lessee, 59 U.S. (18 How.) 272, 285 (1855). ↑

-

. NCLU Brief, supra note 1, at *3–4. ↑

-

. Baude, supra note 38, at 1578. ↑

-

. Crowell v. Benson, 285 U.S. 22, 50 (1932). ↑

-

. See Sward, supra note 134, at 1079. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Glassman, supra note 17, at 68. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Sward, supra note 134, at 1080. ↑

-

. Jonathan H. Adler, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Jarkesy v. SEC, Volokh Conspiracy (Aug. 17, 2022, 6:10 p.m.) https://reason.com/volokh/2022/08/17/the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly-of-jarkesy-v-sec/; see id. (“[T]he Fifth Circuit’s arguments that Atlas Roofing has been abrogated . . . [is] thoroughly unconvincing.”). ↑

-

. Jarkesy v. SEC, 34 F.4th 446, 450 (5th Cir. 2022), cert. granted, 143 S. Ct. 2688 (2023). ↑

-

. Id. at 451, 465. ↑

-

. Id. at 451. ↑

-

. See Granfinanciera, S.A. v. Nordberg, 492 U.S. 33, 42 (1989) (emphasis added). ↑

-

. See discussion infra Section II.A.1. ↑

-

. Granfinanciera, 492 U.S. at 42 (emphasis added). ↑

-

. Id. at 49 (emphasis added). ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Jarkesy v. SEC, 34 F.4th 446, 451 (5th Cir. 2022), cert. granted, 143 S. Ct. 2688 (2023). ↑

-

. Granfinanciera, S.A. v. Nordberg, 492 U.S. 33, 53–54 (1977). ↑

-

. Jarkesy, 34 F.4th at 454. ↑

-

. Granfinanciera, 492 U.S. at 60–63 (quoting Atlas Roofing Co. v. Occupational Safety & Health Rev. Comm’n, 430 U.S. 442, 461 (1977)). ↑

-

. Jarkesy, 34 F.4th at 454–57. ↑

-

. Atlas Roofing, 430 U.S. at 453. ↑

-

. Jarkesy, 34 F.4th at 458 (citing Atlas Roofing, 430 U.S. at 445). ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Oral Argument at 25:50, Jarkesy 34 F.4th 446 (No. 20–61007), https://www.courtlistener.com/audio/77971/jarkesy-v-sec/. ↑

-

. 15 U.S.C. § 78. Several of the Justices seemed to find this analogy fitting. See Transcript of Oral Argument at 100, 115, 146, SEC v. Jarkesy, 143 S. Ct. 2688 (2023) (No. 22-859). ↑

-

. See Jarkesy, 34 F. 4th at 455 (“The traditional elements of common-law fraud are (1) a knowing or reckless material misrepresentation, (2) that the tortfeasor intended to act on and (3) that harmed the plaintiff.” (quoting In re Deepwater Horizon, 857 F.3d 246, 249 (5th Cir. 2017)) (emphasis added)). ↑

-

. Jarkesy, 34 F. 4th at 472 (Davis, J., dissenting). ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. at n.47. ↑

-

. Id. at 456 (majority opinion) (citing Atlas Roofing v. Occupational Safety & Health Rev. Comm’n, 430 U.S. 442, 445 (1977)). ↑

-

. See 15 U.S.C § 78u-2. ↑

-

. Atlas Roofing, 430 U.S. 442, 453 (1977). ↑

-

. Granfinanciera, S.A. v. Nordberg, 492 U.S. 33, 60–63 (1977). ↑

-

. Jarkesy, 34 F.4th at 456. ↑

-

. See id. ↑

-

. Id. at 455–56. ↑

-

. Id. at 456. ↑

-

. See Adler, supra note 197. ↑

-

. Jarkesy, 34 F.4th at 459. ↑

-

. Id. at 460. ↑

-

. Id. at 461 (quoting Crowell v. Benson, 285 U.S. 22, 50 (1992)). ↑

-

. See Oceanic Steam Navigation Co. v. Stranahan, 214 U.S. 320, 339 (1909). ↑

-

. Jarkesy, 34 F.4th at 461 (quoting INS v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983)). ↑

-

. Crowell v. Benson, 285 U.S. 22, 50 (quoting Ex parte Bakelite Corp., 279 U.S. 438, 451 (1929)). ↑

-

. Mistretta v. United States, 488 U.S. 361, 372 (1989). ↑

-

. Jarkesy, 34 F.4th at 462. ↑

-

. Elena Kagan, Presidential Administration, 114 Harv. L. Rev. 2245, 2364 (2001). ↑

-

. See Brandon J. Johnson, The Accountability–Accessibility Disconnect, 58 Wake Forest L. Rev. 65, 74–80 (2023). ↑

-

. See Jarkesy, 34 F.4th at 460 (citing Gundy v. United States, 139 S. Ct. 2116, 2134 (2019) (Gorsuch, J., dissenting)). ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. See Granfinanciera, S.A., v. Nordberg, 492 U.S 33, 51 (1989). ↑

-

. Id. at 42. ↑

-

. Id. at n.4. ↑

-

. See discussion supra Part II.A.2. ↑

-

. Granfinanciera, 492 U.S. at 49. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Id. ↑

-

. Atlas Roofing Co. v. Occupational Safety & Health Rev. Comm’n, 430 U.S. 442, 450 (1977) (emphasis added). ↑

-

. 279 U.S. 438 (1929). ↑

-

. Id. at 451. ↑

-

. Id. at 589 (quoting N. Pipeline Constr. Co. v. Marathon Pipeline Co., 458 U.S. 50, 68 (1982) (plurality opinion)). ↑

-

. See Jarkesy v. SEC, 34 F.4th 446, 461 (5th Cir. 2022), cert. granted, 143 S. Ct. 2688 (2023). ↑

-

. Granfinanciera, S.A. v. Nordberg, 492 U.S. 33, 49 (1989). ↑

-

. See, e.g., Transcript of Oral Argument at 119–20, SEC v. Jarkesy, 143 S. Ct. 2688 (2023) (No. 22-859) (Justice Sotomayor expressing concern that finding for Jarkesy could nullify all agency adjudication). ↑

-

. See, e.g., Transcript of Oral Argument at 27, SEC v. Jarkesy, 143 S. Ct. 2688 (2023) (No. 22-859) (Justice Kavanaugh expressing concern that the government throws a different label on a suit and can deprive litigants of jury trials and other due process rights in civil litigation). ↑

-

. Consent overcomes any assignment problems. “The entitlement to an Article III adjudicator is a ‘personal right’ and thus ordinarily ‘subject to waiver.’” Wellness Int’l Network, Ltd. v. Sharif, 575 U.S. 665, 678 (2015) (quoting Commodity Futures Trading Comm’n v. Schor, 478 U.S. 833, 848 (1986)). ↑

-

. Transcript of Oral Argument at 135–36, Jarkesy, 143 S. Ct. 2688 (No. 22-859); see also Christopher J. Walker & David Zaring, The Right to Remove in Agency Adjudication, 84 Ohio St. L.J. (forthcoming 2024) (manuscript at 33), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4644940. ↑

-

. 5 U.S.C. § 553. ↑

-

*. J.D. Candidate 2024 Wake Forest University School of Law; B.S. Finance Brigham Young University; incoming associate at Morris Nichols Arsht & Tunnell. The biggest thank you goes to my wife Brooke, and our kids Scott, Liam, and Sonya (Sunny), their love and support means more than I can express here. Also thank you to Christian Schweitzer who has been a mentor to me since my 1L year and provided so much help and support as editor of the note. For helpful feedback and discussion, I would like to thank Professors Christine Coughlin, Lee-ford Tritt, and Sidney Shapiro. Finally, a huge thank you for the Law Review team, specifically Keegan Hicks, Dylan Ellis, and Haley Hurst, each of them made my note much clearer. ↑