Sydney Basden

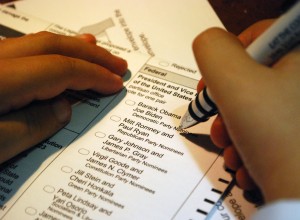

The 2024 Presidential election is mere weeks away, and North Carolinians on both sides of the political aisle are being reminded to vote.[1] With North Carolina expected to be a key swing state in the Electoral College,[2] the political advertisements seem to be never-ending, via television commercials, internet ads, phone calls, texts, and physical mail. However, some voting rights activists are worried that previously registered, eligible voters may be in for a surprise on Election Day: they are no longer registered to vote due to so-called “voter purges.”[3]

State Election Officials Face Lawsuit

North Carolina has long enshrined the right of the people to vote, as set out in Article VI of the state constitution,[4] but the maintenance – or alleged lack thereof – of voter registration rolls has been called into question in a recent lawsuit.[5] The Republican National Committee (RNC) and North Carolina Republican Party (NCGOP) claim that the North Carolina State Board of Elections (NCSBE) has violated the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) by not requiring certain forms of identification before processing approximately 225,000 voter registration forms.[6] HAVA requires the state to have either an applicant’s driver’s license number or the last four digits of their social security number before processing the registration, barring specific circumstances.[7] However, the complaint alleges prior NCSBE registration forms did not designate these fields as “required,” and the state allegedly still processed the applications, potentially without a required form of identification.[8] The RNC and NCGOP are requesting the court order the state to either remove all ineligible registrations before the November election or require those registrants to vote via provisional ballot until their identification is provided.[9]

This lawsuit arose out of a 2023 complaint by North Carolina voter Carol Snow to the NCSBE, who alleged that the state’s voter registration form did not adhere to HAVA because it did not require a driver’s license or social security number.[10] The NCSBE agreed with Snow and voted unanimously to make changes in a board meeting in late 2023.[11] However, the bipartisan NCSBE unanimously rejected her request to go back and contact the approximately 225,000 voters to confirm their eligibility.[12] The plaintiffs filed their complaint in part due to this board decision.[13]

Voter registration and fraud have been a hot-button issue in American politics for years,[14] and the issue was only exacerbated further in the 2020 election.[15] The RNC and NCGOP address the politics of the issue in their lawsuit: “Not only will Plaintiffs’ members be disenfranchised [if the court does not rule in Plaintiffs’ favor], but Plaintiffs’ mission of advocating for Republican voters, causes, and candidates will be impeded by contrary votes of potentially ineligible voters.”[16]

Attempts at Intervention

On the other side of the hypothetical political aisle, however, both the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and the North Carolina State Conference of the NAACP (NAACP) have filed motions to intervene in the lawsuit as defendants.

The NAACP’s request for intervention includes an intervention by a North Carolina resident, Jackson Jones, who is reportedly one of the 225,000 voters whose registrations are being questioned.[17] According to the NAACP’s motion, Jones has voted in North Carolina for more than three decades and recently re-registered to vote after moving.[18] Although he has provided his driver’s license and social security number to election officials in the past, he is allegedly included on the list of potentially ineligible voters.[19] Additionally, the NAACP claims that the RNC and NCGOP lack evidentiary support for their allegations that the 225,000 voters are ineligible.[20] It also says the NCSBE’s registration form not requiring this identifying information “cannot and does not justify purging individual voters, who would find themselves kicked off the rolls through no fault of their own.”[21] Furthermore, the NAACP alleges that Black voters are disproportionality more likely than white voters to appear on the list and have their right to vote disenfranchised.[22]

The DNC also seeks to intervene in the lawsuit, claiming the RNC and NCGOP’s requests are prohibited by the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA).[23] A portion of the NVRA requires states to complete the systematic removal of ineligible voters “not later than 90 days prior” to an election.[24] The DNC seeks to intervene because it wants to ensure its voting members, and other voters who support Democratic candidates, can vote in the upcoming election.[25]

In a direct response to the political allegations made in the RNC and NCGOP’s complaint, the DNC responded: “The RNC alleges that disenfranchising 225,000 North Carolina voters will give it a competitive advantage in this year’s general election. The DNC has a mirror-image interest in ensuring that eligible voters can cast votes for Democratic candidates.”[26]

What Happens Now

Preventing voter fraud via voter registration maintenance has long been the topic of many state statutes and lawsuits,[27] and several other state boards of election are facing voter roll lawsuits from the RNC and state Republican Party organizations.[28] This issue is deeply political and partisan. As an example, both the RNC and DNC’s filings in this North Carolina lawsuit used politically charged language, decrying the other party’s claims as partisan while including partisan language of their own.

However, an Associated Press report completed in late 2021 found that “suspected fraud is both generally detected and exceptionally rare” after analyzing allegations of voter fraud in six battleground states in the 2020 election.[29] While the report did not specifically look at North Carolina ballots, it echoed investigations and court cases across the country: voter fraud is not a widespread issue.[30]

Judges will play a crucial role in deciding issues of voter registration and potential disenfranchisement, and because the election is merely weeks away, judges will need to decide these cases quickly.[31] It is the role of the judiciary to uphold the United States Constitution and laws, as well as the Constitution and laws of the state of North Carolina.[32] However, judges in North Carolina are elected by partisan ballot, and some judicial seats are hotly contested in this election.[33] Depending on the way this case is decided at the Superior Court level, any appeals to the state Court of Appeals or State Supreme Court could get deeply political. There is the potential for partisanship and election polling to sway a judge’s opinion. Even if judges uphold their oath of office and do not consider politics when ruling, it is election season, so the losing side will almost certainly cry foul.

[1] For information on North Carolina voter registration and deadlines, see Upcoming Election, N.C. State Bd. of Elections, https://www.ncsbe.gov/voting/upcoming-election (last visited Sept. 14, 2024).

[2] Elliot Davis Jr., The 2024 Swing States: Why North Carolina Could Sway the Presidential Election, U.S. News (Sept. 12, 2024, 5:42 PM), https://www.usnews.com/news/elections/articles/the-2024-swing-states-north-carolina-could-sway-the-2024-election.

[3] Voter Purges, Brennan Ctr. for Just., https://www.brennancenter.org/issues/ensure-every-american-can-vote/vote-suppression/voter-purges (last visited Sept. 13, 2024).

[4] N.C. Const. art. VI.

[5] Complaint at 2, Republican Nat’l Comm. v. N.C. State Bd. of Elections, No. 24CV026995-910 (N.C. Sup. Ct. filed Aug. 30, 2024).

[6] Id.

[7] Help America Vote Act § 303, 52 U.S.C. § 21083(a)(5).

[8] Complaint, supra note 4, at 9.

[9] Id. at 19–20.

[10] See N.C. HAVA Administrative Complaint Form filed by Carol L. Snow (Oct. 6, 2023), https://s3.amazonaws.com/dl.ncsbe.gov/State_Board_Meeting_Docs/2023-11-28/Snow%20Amended%20HAVA%20Complaint.pdf.

[11] Theresa Opeka, NCSBE Certifies Elections, Changes Absentee Ballot Distribution Date, The Carolina J. (Nov. 30, 2023), https://www.carolinajournal.com/ncsbe-certifies-elections-changes-absentee-ballot-distribution-date/.

[12] Will Duran, In Bipartisan Vote, NC Elections Board Shoots Down ‘Audit Force’ Allegations of Election Violations, WRAL (Apr. 11, 2024, 11:28 PM), https://www.wral.com/story/in-bipartisan-vote-nc-elections-board-shoots-down-audit-force-allegations-of-election-violations/21375951/.

[13] Complaint, supra note 4, at 14.

[14] Dayna L. Cunningham, Who Are to Be the Electors? A Reflection on the History of Voter Registration in the United States, 9 Yale L. & Pol’y Rev. 370, 373 (1991).

[15] Jason Marisam, Fraudulent Vote Dilution, 2 Fordham L. Voting Rts. & Democracy F. 197, 198 (2024).

[16] Complaint, supra note 4, at 16.

[17] Motion to Intervene as Defendants and to Expedite Consideration of Same at 6, Republican Nat’l Comm. v. N.C. State Bd. of Elections, No. 24CV026995-910 (N.C. Sup. Ct. filed Sept. 4, 2024) (filing made by North Carolina State Conference of the NAACP and Jackson Sailor Jones).

[18] Id.

[19] Id.

[20] Id.

[21] Id. at 2.

[22] Id. at 5 (“Upon information and belief, Black voters comprise at least 22 percent of these registrants on the list who have demographic information included in their registration file, and Black voters are disproportionately more likely than white voters to appear on the list.”).

[23] Motion to Intervene by the Democratic National Committee at 2, Republican Nat’l Comm. v. N.C. State Bd. of Elections, No. 24CV026995-910 (N.C. Sup. Ct. filed Aug. 30, 2024).

[24] National Voter Registration Act § 8, 52 U.S.C. § 20507(c)(2)(A).

[25] Id. at 3.

[26] Id. at 4.

[27] Michael Morse, Democracy’s Bureaucracy: The Complicated Case of Voter Registration Lists, 103 B.U. L. Rev. 2123, 2177 (2023).

[28] See, e.g., Complaint, Mussi v. Fontes, No. CV-24-1310-PHX-DWL (D. Ariz. filed May 31, 2024); Complaint, Republican National Committee v. Benson, No. 1:24-cv-00262 (W.D. Mich. filed Mar. 13, 2024); Complaint, Dagusen v. Aguilar (Nev. D. Ct. filed Sept. 11, 2024), https://prod-static.gop.com/media/documents/Sept._2024_Complaint__1_1726087424.pdf. As of Sept. 13, 2024, these cases had not been decided and were still pending in their respective courts.

[29] Christina A. Cassidy, Far Too Little Voter Fraud to Tip Election to Trump, AP Finds, The Associated Press (Dec. 14, 2021, 5:56 PM), https://apnews.com/article/voter-fraud-election-2020-joe-biden-donald-trump-7fcb6f134e528fee8237c7601db3328f.

[30] Id.

[31] In an effort to help courts and lawmakers handle the recent onslaught of litigation involving voter registration and voter rolls, the United States Department of Justice recently released additional guidance on the provision of the National Voter Registration Act. See Civ. Rts. Div., U.S. Dep’t of Just. Voter Registration List Maintenance: Guidance under Section 8 of the National Voter Registration Act, 52 U.S.C. § 20507 (2024), https://www.justice.gov/crt/media/1366561/dl.

[32] About North Carolina Courts, N.C. Jud. Branch, https://www.nccourts.gov/about (last visited Sept. 13, 2024).

[33] Judicial Voter Guide: 2024 General Election, N.C. State Bd. of Elections, https://www.ncsbe.gov/voting/upcoming-election/judicial-voter-guide-2024-general-election (last visited Sept. 13, 2024).